42nd Infantry Division (United States)

| 42nd Infantry Division | |

|---|---|

42d ID Shoulder Sleeve Insignia | |

| Active | 1917–1919 1943–1946 1947–present |

| Country | United States |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | Division |

| Garrison/HQ | Glenmore Road Armory, Troy, NY |

| Nickname(s) | "Rainbow" (special designation)[1] |

| Motto(s) | Never Forget! |

| Engagements | |

| Commanders | |

| Current commander | MG Jack James |

| Notable commanders | Major General W. A. Mann Major General Charles T. Menoher Major General Charles D. Rhodes Brigadier General Douglas MacArthur Major General C. A. F. Flagler Major General George W. Read Major General Harry J. Collins Major General Martin H. Foery Major General Joseph J. Taluto |

| Insignia | |

| Distinctive unit insignia |  |

The 42nd Infantry Division (42ID) ("Rainbow"[1]) is a division of the United States Army National Guard. It was nicknamed the Rainbow Division because, during rapid mobilization for service in WW1, it was formed from 27 National Guard units from across the US. The division was engaged in four major operations between July 1918 and the armistice in November 1918, and demobilized in 1919. Since World War I, the 42nd Infantry Division has served in World War II and the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT).

The division is currently headquartered at the Glenmore Road Armory in Troy, New York. The division headquarters is a unit of the New York Army National Guard. The division currently includes Army National Guard units from fourteen different states, including Connecticut, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont. As of 2007[update], 67 percent of 42ID soldiers are located in New York and New Jersey.[2]

World War I

[edit]

Rainbow Division

[edit]When the United States entered World War I by declaring war on Germany in April 1917, it federalized the National Guard and organized many of its units into divisions to quickly build up the Army. Douglas MacArthur, then a major, suggested to William Abram Mann, the head of the Militia Bureau, that he form a division from the units of several states that had not been assigned to divisions. Secretary of War Newton D. Baker approved the proposal, and recalled MacArthur saying that such an organization would "stretch over the whole country like a rainbow."[3]

On 1 August 1917, the War Department directed the formation of a composite National Guard division, comprising units from 26 states and the District of Columbia. As a result, the 42nd Division came to be known as the "Rainbow Division". The name stuck, and MacArthur was promoted to colonel and became the division's chief of staff, with Mann as its commander.[4]

The 42nd Division was assembled in August 1917 at Camp Mills, New York, four months after the American entry into World War I. The 42nd arrived overseas to the Western Front of Belgium and France in November 1917, one of the first divisions of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) to do so, under the command of Major General William A. Mann although he was soon to be replaced by Major General Charles T. Menoher, who remained in this position for the rest of the war. Colonel Douglas MacArthur was the division's chief of staff until he later went on to command the 84th Brigade of the division.[5] The AEF was commanded by General John Joseph Pershing. After initially landing at St. Nazaire (France), the 42nd was temporarily located at Vaucouleurs, Lorraine (France), from 7 November – 7 December 1917, to preliminarily train before transferring to another training area between Lafauche and Rimaucourt.[6] The day after Christmas, the 42nd, along with other divisions it had now linked up with, departed for another training area near Rolampont, Langres (France).[7] French officers had been attached to the 42nd at Lafauche, Rimaucourt, and Rolampont as instructors in trench warfare who "...seemed, from Menoher and MacArthur's view, to think more highly of the Rainbow's performance than did Pershing and his Chaumont staff".[8]

"On February 13, 1918, the day that the [3-day] inspection [by General Pershing's headquarter's staff from Chaumont] was completed, Pershing ordered the 42nd division to move to the Lunéville sector of southern Lorraine for a month's training at the front with the French VII Corps".[9] "Rainbow division entrained for the Lunéville sector on February 16, 1918, and it was joined by the 67th Field Artillery Brigade shortly thereafter.[10] Rainbow's soldiers were distributed over the entire sixteen-mile front of the sector, from Lunéville past St. Clément to Baccarat.[11] As far as administration, supply, and discipline were concerned, the division was part of MG Hunter Liggett's I Corps, A.E.F., but for combat and training purposes it was under Major General Georges de Bazelaire, of the French VII Army Corps, with each of the 42nd's Regiments assigned to one of the French Divisions holding the sector.[11] Each American battalion served one week at a time on the front line, then spent the next week on the second line of defense, and the third week in reserve[11] Acute Shortages of some types of equipment still existed, as evidenced, for example, by Menoher's order that troops of a battalion leaving the front line were to yield their pistols to the men of the relieving battalion".[12]

On 16 June 1918, General Pershing ordered the 42nd to entrain to "the Champagne region east of Rheims (a sector comparatively more active than Baccarat) to be assigned to General Henri Gouraud's Fourth Army"; relinquishing the current Baccarat sector "to the relieving American 77th and French 61st divisions".[13]

During 1918, Rainbow division, specifically with the 67th Field Artillery's "1650 projectiles" in the Bois des Chiens, engaged German forces with and experienced bombardment by German forces with deadly, poison-gas Bombardments, specifically with German 75-mm. and 105-mm. shells filled with palite and yperite (also known as Mustard gas).[14] The 42nd took part in four major operations during the last four months of World War I: the Champagne-Marne, the Aisne-Marne, the Battle of Saint-Mihiel, and the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. In total, it saw 164 days of combat, third behind only the 1st Infantry Division (220 days) and 26th Infantry Division (193 days).

- Casualties: total 14,683 (KIA/DOW – 2,810; WIA – 11,873).[15]

- Commanders: MG W. A. Mann (5 September 1917), Brig. Gen. Charles T. Menoher (19 December 1917), Maj. Gen. Charles D. Rhodes, (7 November 1918), Brig. Gen. Douglas MacArthur (10 November 1918), Maj. Gen. C. A. F. Flagler (22 November 1918), Brig. Gen. George G. Gatley (28 March 1919), Maj. Gen. George Windle Read (10 April 1919 to Division's deactivation on 9 May 1919).

The 42nd Division was demobilized in May 1919 at Camp Upton, New York, Camp Grant, Illinois, Camp Dix, New Jersey, and Camp Dodge, Iowa.

Rainbow unit insignia

[edit]

The 42nd Division adopted a shoulder patch and distinctive unit insignia acknowledging the nickname.[16][17] Division lore includes the story that division commander Charles T. Menoher approved the patch after observing a rainbow shortly before a battle, deciding this was a favorable omen.[18] The original version of the patch symbolized a half arc rainbow and contained thin bands in multiple colors.[19][20][21] During the latter part of World War I and post war occupation duty in Germany, the patch was changed to a quarter arc.[18] According to the division's official history, Colonel William N. Hughes Jr., who had succeeded MacArthur as chief of staff, was credited with modifying the design to a quarter arc in an attempt to standardize it.[18] According to World War I veterans of the 42nd Division, soldiers removed half the original symbol to memorialize the half of the division's soldiers who had been killed or wounded during the war.[19][22] They also reduced the number of colors to just red, gold and blue bordered in green, to standardize the design and make the patch easier to reproduce.[18][21]

Description: The 4th quadrant of a rainbow with three bands of color: red, gold and blue, each 3/8-inch (.95 cm) in width, outer radius 2 inches (5.08 cm); all within a 1/8-inch (.32 cm) Army green border.[16]

Background: The shoulder sleeve insignia was originally authorized by telegram on 29 October 1918.[16] It was officially authorized for wear on 27 May 1922.[16] It was reauthorized for wear when the division was reactivated for World War II.[16] On 8 September 1947, it was authorized for the post-World War II 42nd Infantry Division when it was reactivated as a National Guard unit.[16]

Order of battle

[edit]

- Headquarters, 42nd Division (future General of the Army, then Colonel Douglas MacArthur, served as the chief of staff of the 42nd Division)

- 83rd Infantry Brigade

- 165th Infantry Regiment (formerly 69th Infantry, New York National Guard)

- Notable members: Major William "Wild Bill" Donovan, Chaplain Francis P. Duffy, Sergeant Joyce Kilmer

- Significant events: Rouge Bouquet

- 166th Infantry Regiment (formerly 4th Infantry, Ohio National Guard)

- 150th Machine Gun Battalion (formerly Companies E, F, and G, 2nd Infantry, Wisconsin National Guard)

- 165th Infantry Regiment (formerly 69th Infantry, New York National Guard)

- 84th Infantry Brigade (this was the brigade that Brigadier General Douglas MacArthur commanded from July 1918 to November 1918)

- 167th Infantry Regiment (formerly 4th Infantry, Alabama National Guard)

- 168th Infantry Regiment (formerly 3rd Infantry, Iowa National Guard)

- 151st Machine Gun Battalion (formerly Companies B, C, and F, 2nd Infantry, Georgia National Guard)

- 67th Field Artillery Brigade

- 149th Field Artillery Regiment (75 mm) (formerly 1st Field Artillery, Illinois National Guard)

- 150th Field Artillery Regiment (155 mm) (formerly 1st Field Artillery, Indiana National Guard)

- 151st Field Artillery Regiment (75 mm) (formerly 1st Field Artillery, Minnesota National Guard)

- 117th Trench Mortar Battery (formerly 3rd and 4th Companies, Coast Artillery, Maryland National Guard)

- 149th Machine Gun Battalion (formerly 3rd Battalion, 4th Infantry, Pennsylvania National Guard)

- 117th Engineer Regiment (formerly Separate Battalions, Engineers, California and South Carolina National Guards)

- 117th Field Signal Battalion (formerly 1st Battalion, Signal Corps, Missouri National Guard)

- Headquarters Troop, 42nd Division (formerly 1st Separate Troop, Cavalry, Louisiana National Guard)

- 117th Train Headquarters and Military Police (formerly 1st and 2nd Companies, Coast Artillery, Virginia National Guard)

- 117th Ammunition Train (formerly 1st Ammunition Train, Kansas National Guard)

- 117th Supply Train (formerly Supply Train, Texas National Guard)

- 117th Engineer Train (formerly Engineer Train, North Carolina National Guard)

- 117th Sanitary Train (165th–168th Ambulance Companies and Field Hospitals)

- 165th Ambulance Company (formerly 1st Ambulance Company, Michigan National Guard)

- 165th Field Hospital (formerly 1st Field Hospital, Washington, D.C. National Guard)

- 166th Ambulance Company (formerly 1st Ambulance Company, New Jersey National Guard)

- 166th Field Hospital (formerly 1st Field Hospital, Nebraska National Guard)

- 167th Ambulance Company (formerly 1st Ambulance Company, Tennessee National Guard)

- 167th Field Hospital (formerly 1st Field Hospital, Oregon National Guard)

- 168th Ambulance Company (formerly 1st Ambulance Company, Oklahoma National Guard)

- 168th Field Hospital (formerly 1st Field Hospital, Colorado National Guard

Interwar period

[edit]As the 42nd was a composite division, it was not contemplated for reorganization after World War I, and all of its former elements were assigned to other National Guard divisions or remained demobilized.

World War II

[edit]- Activated: 14 July 1943

- Overseas: November 1944.

- Campaigns: Ardennes-Alsace, Rhineland, Central Europe.

- Days of combat: 106.

- Prisoners of war taken: 59,128.

- Presidential Unit Citation: 2.

- Awards: MH-1 ; DSC-4 ; DSM-1 ; SS-622; LM-9; SM-32; ; BSM-5,325 ; AM-104.

- Commanders: Maj. Gen. Harry J. Collins commanded the 42ID during its entire period of federal service in World War II.

- Deactivated: 29 June 1946 in Europe.

Order of battle

[edit]- Headquarters, 42nd Infantry Division

- Headquarters and Headquarters Battery, 42nd Infantry Division Artillery

- 232nd Field Artillery Battalion (105 mm)

- 392nd Field Artillery Battalion (105 mm)

- 402nd Field Artillery Battalion (105 mm)

- 542nd Field Artillery Battalion (155 mm)

- 142nd Engineer Combat Battalion

- 122nd Medical Battalion

- 42nd Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop (Mechanized)

- Headquarters, Special Troops, 42nd Infantry Division

- Headquarters Company, 42nd Infantry Division

- 742nd Ordnance Light Maintenance Company

- 42nd Quartermaster Company

- 132nd Signal Company

- Military Police Platoon

- Band

- 42nd Counterintelligence Corps Detachment[23]

When reconstituted in the Army of the United States on 5 February 1943, the 42ID was a unique unit, as it continued the lineage of the Rainbow Division from World War I. Army Ground Forces filled the division with personnel from every state, and from the division's standup at Camp Gruber on 14 July 1943 until the division stood down in Austria, at every formal assembly, the division displayed not only the national and divisional colors, but all 48 state colors (state flags). To emphasize the 42ID's continued lineage from the 42ID of World War I, division commander Major General Harry J. Collins issued the orders that activated the unit on 14 July, the eve of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Champagne-Marne campaign in France.[24]

During 1944, the 42nd Infantry Division was subject to large-scale removals of personnel to adhere to War Department policies stating that the greatest possible proportion of men sent overseas as replacements should have at least six months of training, prohibiting the sending of soldiers who were younger than nineteen or who had children conceived prior to Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor overseas as replacements unless men could be found from other sources, to supplement the capacity of replacement training centers, and to build up a reserve of replacements for Operation Overlord. Between April and September 1944, the 42nd Infantry Division lost 3,936 infantrymen, 840 field artillerymen, and 45 cavalrymen. In mid-October 1944, 25% of the men in the division's regiments had been members only since January 1944, 20% had joined from replacement training centers during the past thirty days, 20% were former Army Specialized Training Program students or aviation cadets with approximately five months of training in the division, and 35% were men from other arms, principally antiaircraft, with approximately four months of training in the division.

Combat chronicle

[edit]The three infantry regiments (222nd, 232nd, & 242nd) and a detachment of the 42ID Headquarters arrived in France at Marseille on 8 to 9 December 1944, and were formed into Task Force (TF) Linden, under Henning Linden, the Assistant Division Commander (ADC).[25] As part of the Seventh Army's VI Corps, TF Linden entered combat in the vicinity of Strasbourg, relieving elements of the 36ID on 24 December 1944.[25]

While defending on a 31-mile sector along the Rhine north and south of Strasbourg in January 1945, TF Linden repulsed a number of enemy counterattacks at Hatten and other locations during the German "Operation Northwind" offensive.[25] At the headquarters of 1st Battalion, 242nd Infantry, Private First Class Vito R. Bertoldo waged a 48-hour defense of the battalion command post, for which he received the Medal of Honor. When the command post was attacked by a German tank with its 88-mm. gun and machine gun fire, Bertoldo remained at his post, and with his own machine gun killed the occupants of the tank when they tried to remove mines which were blocking their advance.[26] On 24 and 25 January 1945, in the Bois D'Ohlungen, and the vicinity of Schweighouse-sur-Moder and Neubourg, the 222nd Infantry Regiment held a position covering a front of 7,500 yards, three times the normal frontage for a regiment in defense. After a two-hour artillery bombardment, the 222nd Infantry Regiment was repeatedly attacked by elements of the German 7th Parachute, 47th Volks Grenadier Division, and the 25th Panzer Grenadier Division. During the ensuing struggle, one company of the 222nd Infantry was surrounded, but withdrew from their position and infiltrated back through the Germans to the regimental lines after exhausting all but 35 rounds of ammunition. For 24 hours, the battle raged, but the Germans were never able to break through the 222nd lines. For this action the 222nd Infantry Regiment was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation (2001). After these enemy attacks, TF Linden returned to reserve of the 7th Army and trained with the remainder of the 42ID which had arrived in the meantime.

On 14 February 1945, the 42ID as a whole entered combat.[25] Initially occupying defensive positions near Haguenau, after a month of patrolling in the Hardt Forest, the division went on the offensive.[25] During the night of 27 February, elements of the German 6th Mountain Division were withdrawn under cover of heavy artillery and mortar fire and replaced by the 221st Volksgrenadier Regiment. In the brief period this unit had been in the line, German soldiers had come to fear the 42nd Division's patrols and raids. "Is your Division a part of Roosevelt's SS?" asked one German when captured. The remark circulated and men kidded each other about being in the Rainbow SS.[27] The 42ID attacked through the Hardt Forest during 15 to 21 March, broke through the Siegfried Line, and cleared Dahn and Busenberg, while Third Army created and expanded bridgeheads across the Rhine.[25] Moving across the Rhine on 31 March, the division captured Wertheim am Main on 1 April and Würzburg on 6 April, following a fierce battle from 2 to 6 April.[25] Schweinfurt fell next after hand-to-hand engagements during the period of 9 to 12 April.[25] Fürth, near Nuremberg, put up fanatical resistance on 18 and 19 April but was taken by the 42ID.[25]

On 25 April, the 42ID captured Donauwörth on the Danube.[25] On 29 April, units of the 42nd Division liberated some 30,000 inmates at Dachau concentration camp.[28] In mid-May, 42nd Division patrols arrested German war criminal Arthur Greiser and Waffen-SS officer Heinz Reinefarth.[29]

Casualties

[edit]

- Total battle casualties: 3,971[30]

- Killed in action: 553[30]

- Wounded in action: 2,212[30]

- Missing in action: 31[30]

- Prisoner of war: 1,175[30]

Assignments in ETO

[edit]- 10 December 1944: Seventh Army, 6th Army Group

- 15 December 1944: Third Army, 12th Army Group

- 24 December 1944: VI Corps, Seventh Army, 6th Army Group

- 25 March 1945: XXI Corps, Seventh Army, 6th Army Group

- 19 April 1945: XV Corps, Seventh Army, 6th Army Group

The 42nd Division ended World War II on occupation duty in Austria and was inactivated by the end of January 1947.[31]

Cold War

[edit]On 13 October 1945, the War Department published a postwar policy statement for the entire Army.[31] After the policy statement was published, the Army Staff prepared a postwar National Guard troop basis, which included twenty-four divisions, including the 42nd Infantry Division. Most soldiers considered the 42nd, initially organized with state troops in 1917, as a Guard formation. During the process, New York successfully petitioned the War Department for the 42nd Infantry Division. After the state governors formally notified the National Guard Bureau that they accepted the new troop allotments, the bureau authorized reorganization of the units with 100 percent of their officers and 80 percent of their enlisted personnel. By September 1947, the 42nd Division headquarters, along with all the other new Guard divisional headquarters, had received federal recognition.

In April 1963, the 42nd Division was reorganized under the Reorganization Objective Army Division structure.[32] From 1967 to 1969, the division was briefly part of the Selected Reserve Force, designed to reinforce the active army in Vietnam. In a 1968 reorganization, the division was split between the New York Army National Guard and the Pennsylvania Army National Guard.[33] In 1973–74, the division was converted back into an all-New York organization.

The 42nd Infantry Division absorbed the units of the 26th Infantry Division and the 50th Armored Division of the Massachusetts and New Jersey Army National Guard, respectively, in post-Cold War restructuring. All three divisions were severely understrength, so the assets of the three were combined into one. The 50th Brigade, created from the assets of the disbanding 50th Armored Division, was initially assigned to the 42nd Infantry Division as an armored brigade, but was transformed to an infantry brigade combat team (BCT) in the very first years of the 21st century as part of Army modularity.

In the 1970s, the division headquarters was located at the armory at 125 West 14th Street in Manhattan. It was relocated in December 1989 to the Glenmore Armory in Troy, New York and remains there to this day.[34]

Global War on Terrorism

[edit]Since the 11 September attacks, the 42ID has been extensively involved in the war on terrorism, in both homeland security (HLS) and expeditionary operations. The 42ID's 1–101st Cavalry led the New York Army National Guard's efforts and provided security at Ground Zero during the rescue and then recovery efforts there. 42ID units from the New Jersey Army National Guard provided security at all the major river crossings into New York City and Newark International Airport in the months following 11 September 2001.

The first major overseas effort of the 42ID was the deployment of elements of the 50th BCT/42ID to Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, Cuba. The 2–102nd Armor Battalion deployed as ILO MP's and served with the Joint Detention Operation Group in the detention facility. The 2nd Battalion, 113th Infantry deployed to Guantanamo Bay as well and provided security for the Joint Task Force at Camp Delta. While there elements of the 2nd Battalion, 102nd Armor supported the first military tribunals held at the Guantanamo Bay Detention Facility. Elements have also deployed to the Horn of Africa and Djibouti. New Jersey's 3/112th Field Artillery and 5/117th Cavalry deployed as an ILO Military Police Company with 89th MP Brigade/759th Military Police Battalion; served in Sadr City, and worked alongside the First Cavalry Division. Stationed out of Camp Cuervo (Al Rustimayah) in Baghdad, platoons also worked with U.S. Marines in Fallujah. On 4 June 2004, SSG Carvill and SGT Duffy were killed and the following day the unit lost SPC Doltz and SSG Timoteo.

The 2/108th Infantry deployed to Iraq in 2004. In 2004–05, the 1/69 Infantry served in Iraq, eventually providing security on the Baghdad International Airport (BIAP) Road. The 42nd Combat Aviation Brigade also deployed to Iraq during this period.

In 2004, the division headquarters and division troops of the 42nd Infantry Division deployed as part of Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) III, relieving the 1st Infantry Division (1ID). The division controlled the north-central Iraq area of operations. Serving as the command and control (C2) of Task Force Liberty, the 42ID took over responsibility for the area known as Multi-National Division North Central (MND-NC) including the provinces of Saladin, Diyala, At Ta'amim (Kirkuk) and As Sulymaniah from the 1st Infantry Division on 14 February 2005. The 42ID directed the operations of: 1st BCT, 3ID; 3rd BCT, 3ID; the 278th RCT; 3rd- 313rd Field Artillery, 56th BCT (Texas Army National Guard); and the 116th Cavalry Brigade Combat Team (Idaho, Oregon, and Montana Army National Guard). Soldiers conducted combat actions and raids, seized weapons caches, destroyed improvised explosive devices (IEDs), trained Iraqi army forces, and worked on reconstruction to ensure free elections. 1–69th Infantry of the 42ID manned the checkpoint where Italian SISMI officer Nicola Calipari was shot and killed.

Maj. Gen. Joseph J. Taluto, commanding general of the division during its deployment, commended the many contributions of the 42ID led Task Force Liberty. Vice Chief of Staff of the Army (VCSA), Gen. Richard Cody, saluted members of the 42ID at the unit's homecoming ceremony.[citation needed] The division's Headquarters and Headquarters Company was awarded the Army Meritorious Unit Commendation for its service in Iraq.[35]

In 2008, 26 company-sized elements of the 50th Infantry Brigade Combat Team (IBCT), headquartered at Fort Dix, New Jersey, deployed to Iraq bringing the total number of NJ National Guard soldiers sent to Iraq and Afghanistan to over 3,200. These elements of the 50th IBCT were mobilized for one year, including stateside training and "boots on the ground" in theater. Premobilization training began in 2007 and took place in New Jersey, with further OIF specific preparation conducted at other Army installations out-of-state. Originally slated to deploy to Iraq in 2010, these elements deployed earlier as a result of changes needed to comply with new Department of Defense (DoD) policies. Earlier, in 2007, the DoD had reduced the amount of time units spend overseas in a combat theater, which in turn shifted mobilization schedules and required earlier deployments than anticipated. Elements of the 50th IBCT had deployed in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) previously in 2004.

In 2008, the 27th Infantry Brigade Combat Team (IBCT), headquartered in Syracuse, New York, was mobilized and deployed to Afghanistan to train Afghan National Army (ANA) and police forces. Initial personnel from the 27th IBCT deployed in late 2007, with the majority of the approximately 1,700 service members deployed by mid-2008.

In conjunction around February 2008, soldiers of the 86th Infantry Brigade Combat Team were beginning to receive notification of their upcoming deployment. The Brigade Commander at the time was Colonel William F. Roy. In 2009, the brigade did a rotation at JRTC in Fort Polk, LA. In December 2009, the brigade was officially mobilized and to report to Camp Atterbury, IN. While in Indiana, the brigade trained and prepped for their future deployment to Afghanistan. After receiving numerous replacements and volunteer soldiers, the brigade was sent back to JRTC for one more rotation before they left the country.

The majority of the brigade landed in Afghanistan in early March. The brigade headquarters was on Bagram Airfield in RC-East. The brigade was tasked with numerous missions across eastern Afghanistan. The missions included partnering with the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF), assisting in the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, and securing over 30,000 soldiers on Bagram Airfield while ensuring the base was continuing its daily operations. The brigade left Afghanistan in early December returning to Camp Atterbury, IN. The brigade was released from federal service and returned to the northeast to continue their respective state missions. Several component units of the brigade were awarded the Meritorious Unit Commendation for their service from 8 March 2010 – 4 December 2010 while deployed in support of Operation Enduring Freedom.

Deaths of Esposito and Allen

[edit]Captain Phillip Esposito and First Lieutenant Louis Allen were killed on 7 June 2005, at Forward Operating Base Danger in Tikrit, Iraq by a M18A1 Claymore mine placed in the window of Esposito's office. Esposito was commander, Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 42ID. Allen had recently arrived in Iraq to serve as Esposito's executive officer, or second in command.

Military investigators determined that the mine was deliberately placed and detonated with the intention of killing Esposito and Allen. Staff Sergeant Alberto B. Martinez from the officers' unit was charged in the killing but was acquitted in a court-martial trial at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, on 4 December 2008. The case was one of only two publicly announced alleged fragging incidents among U.S. forces during the Iraq War.

Subsequently, Siobhan Esposito and Barbara Allen, the widows of the officers, continued to pursue justice for their husbands' deaths, pushing for the military to strictly enforce regulations that prohibit threats against superiors and require soldiers to report violations of "good order and discipline."[36]

Homeland security

[edit]During the Cold War and through the present, the 42ID and its soldiers have been regularly called upon for homeland security missions including disaster relief (such as Hurricane Katrina, Hurricane Floyd), emergency preparedness (such as Y2K missions), airport security, critical infrastructure protection, border security, bridge and tunnel security, as well as rail/train station security.

Several first responders to the 11 September 2001 attacks were members of the 42ID, and led much of the military support to the relief and recovery efforts. The 42ID was part of the relief team for the duration of the effort at Ground Zero in New York City. The 42ID has also been actively engaged in missions supporting Operation Noble Eagle.

In October 2005, elements of the 50th Armored Brigade/42 ID were activated for Operation Hurricane Katrina relief in the city of New Orleans. The 2–102nd Armor and the 1–114th Infantry were called to active duty and the combined unit was dispatched to Louisiana to provide security for FEMA. The 50th Brigade arrived at Belle Chase Naval Air Station and from there went to the New Orleans Convention Center. From there, the elements of the 42nd ID sent teams to various parts of the city on various missions of security ranging from roving patrol to security escort for the New Orleans Fire Department and other relief agencies

Organization

[edit]

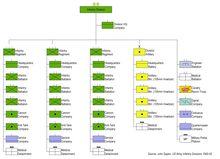

The 42nd Infantry Division exercises training and readiness oversight of the following units:[37]

42nd Infantry Division (NY NG)

42nd Infantry Division (NY NG)

Headquarters and Headquarters Battalion

Headquarters and Headquarters Battalion 27th Infantry Brigade Combat Team (NY NG)

27th Infantry Brigade Combat Team (NY NG)

- Headquarters and Headquarters Company

2nd Squadron, 101st Cavalry Regiment (Reconnaissance Surveillance and Target Acquisition (RSTA))

2nd Squadron, 101st Cavalry Regiment (Reconnaissance Surveillance and Target Acquisition (RSTA)) 1st Battalion, 69th Infantry Regiment

1st Battalion, 69th Infantry Regiment 2nd Battalion, 108th Infantry Regiment

2nd Battalion, 108th Infantry Regiment 1st Battalion, 182nd Infantry Regiment (MA NG)

1st Battalion, 182nd Infantry Regiment (MA NG) 1st Battalion, 258th Field Artillery Regiment

1st Battalion, 258th Field Artillery Regiment- 152nd Brigade Engineer Battalion[38][39]

- 427th Brigade Support Battalion

44th Infantry Brigade Combat Team (NJ NG)

44th Infantry Brigade Combat Team (NJ NG)

- Headquarters and Headquarters Company

1st Squadron, 102nd Cavalry Regiment (RSTA)

1st Squadron, 102nd Cavalry Regiment (RSTA) 2nd Battalion, 113th Infantry Regiment

2nd Battalion, 113th Infantry Regiment 1st Battalion, 114th Infantry Regiment

1st Battalion, 114th Infantry Regiment 1st Battalion, 181st Infantry Regiment (MA NG)

1st Battalion, 181st Infantry Regiment (MA NG) 3rd Battalion, 112th Field Artillery Regiment

3rd Battalion, 112th Field Artillery Regiment 104th Brigade Engineer Battalion

104th Brigade Engineer Battalion 250th Brigade Support Battalion

250th Brigade Support Battalion

86th Infantry Brigade Combat Team (Mountain) (VT NG)

86th Infantry Brigade Combat Team (Mountain) (VT NG)

- Headquarters and Headquarters Company

1st Squadron, 172nd Cavalry Regiment (RSTA)

1st Squadron, 172nd Cavalry Regiment (RSTA) 1st Battalion, 102nd Infantry Regiment (Mountain) (CT NG)

1st Battalion, 102nd Infantry Regiment (Mountain) (CT NG) 1st Battalion, 157th Infantry Regiment (Mountain) (CO NG)

1st Battalion, 157th Infantry Regiment (Mountain) (CO NG) 3rd Battalion, 172nd Infantry Regiment (Mountain) (VT NG, NH NG, ME NG)

3rd Battalion, 172nd Infantry Regiment (Mountain) (VT NG, NH NG, ME NG) 1st Battalion, 101st Field Artillery Regiment (MA NG, VT NG)

1st Battalion, 101st Field Artillery Regiment (MA NG, VT NG) 572nd Brigade Engineer Battalion

572nd Brigade Engineer Battalion 186th Brigade Support Battalion

186th Brigade Support Battalion

42nd Infantry Division Artillery (NY NG)

42nd Infantry Division Artillery (NY NG)

- Headquarters and Headquarters Battery

42nd Combat Aviation Brigade (NY NG)[40]

42nd Combat Aviation Brigade (NY NG)[40]

- Headquarters and Headquarters Company

3rd Battalion (General Support), 126th Aviation Regiment (MA NG, VT NG, MD NG)

3rd Battalion (General Support), 126th Aviation Regiment (MA NG, VT NG, MD NG) 3rd Battalion (Assault), 142nd Aviation Regiment

3rd Battalion (Assault), 142nd Aviation Regiment 1st Battalion (Attack/Recon), 151st Aviation Regiment (SC NG)

1st Battalion (Attack/Recon), 151st Aviation Regiment (SC NG) 1st Battalion (Security and Support), 224th Aviation Regiment (MD NG)

1st Battalion (Security and Support), 224th Aviation Regiment (MD NG) 642nd Aviation Support Battalion

642nd Aviation Support Battalion

42nd Infantry Division Sustainment Brigade (NY NG)

42nd Infantry Division Sustainment Brigade (NY NG)

Attached units

[edit] 26th Maneuver Enhancement Brigade (MA NG)

26th Maneuver Enhancement Brigade (MA NG)

- Headquarters and Headquarters Company

- 211th Military Police Battalion

- 26th Network Signal Company

197th Field Artillery Brigade (NH NG)

197th Field Artillery Brigade (NH NG)

- Headquarters and Headquarters Battery

1st Battalion, 103rd Field Artillery Regiment (M777A2, RI NG)

1st Battalion, 103rd Field Artillery Regiment (M777A2, RI NG) 1st Battalion, 109th Field Artillery Regiment (M109A6 Paladin, PA NG)

1st Battalion, 109th Field Artillery Regiment (M109A6 Paladin, PA NG) 1st Battalion, 119th Field Artillery Regiment (M777A2, MI NG)

1st Battalion, 119th Field Artillery Regiment (M777A2, MI NG) 1st Battalion, 182nd Field Artillery Regiment (M142 HIMARS, MI NG)

1st Battalion, 182nd Field Artillery Regiment (M142 HIMARS, MI NG) 3rd Battalion, 197th Field Artillery Regiment (M142 HIMARS, NH NG)

3rd Battalion, 197th Field Artillery Regiment (M142 HIMARS, NH NG) 1st Battalion, 201st Field Artillery Regiment (M109A6 Paladin, WV NG)

1st Battalion, 201st Field Artillery Regiment (M109A6 Paladin, WV NG) 3643rd Brigade Support Battalion (NH NG)

3643rd Brigade Support Battalion (NH NG) Battery E, 197th Field Artillery Regiment (NH NG)

Battery E, 197th Field Artillery Regiment (NH NG)- 372nd Signal Company (NH NG)

Commanders of the 42nd Infantry Division

[edit]

|

World War II[edit]

World War I[edit]

|

Notable former members

[edit]- Vito Bertoldo, World War II, Medal of Honor[72]

- Boris Bittker, World War II, law professor[73]

- George Emerson Brewer, World War I, surgeon[74]

- Joseph W. Brooks, World War I, college football coach[75]

- Wilber M. Brucker, World War I, United States Secretary of the Army[76]

- Robert Burns, World War II, member of the Iowa Senate[77]

- Frank Merrill Caldwell, World War I, 83rd Infantry Brigade commander[78]

- Kenneth John Conant, World War I, architectural historian[79]

- Hamilton Corbett, World War I, college football player and businessman[80][81]

- Scott Corbett, World War II, journalist and author[82]

- W. Arthur Cunningham, World War I, New York City Comptroller[83]

- Roger W. Cutler Jr., World War II, athlete, attorney and banker[84]

- Reginald B. DeLacour, World War I, adjutant general of Connecticut[85]

- John L. DeWitt, World War I, U.S. Army four-star general[86]

- Michael A. Donaldson, World War I, Medal of Honor[87]

- William J. Donovan, World War I, Medal of Honor[88]

- Francis P. Duffy, World War I, Catholic priest and army chaplain[89]

- Francis J. Evon Jr., Operation Enduring Freedom, Connecticut Adjutant General[90]

- Samuel Warren Hamilton, World War I, psychiatrist[91]

- Thomas S. Hammond, World War I, business executive[92]

- Thomas T. Handy, World War I, U.S. Army four-star general[93]

- Thomas Francis Hickey, World War II, U.S. Army lieutenant general[94]

- Lisa J. Hou, Operation Iraqi Freedom, Adjutant general of the New Jersey National Guard[95]

- Benson W. Hough, World War I, judge of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Ohio[96]

- Kevin Interdonato, Operation Iraqi Freedom, actor[97]

- Olin D. Johnston, World War I, U.S. senator[98]

- Louis Jordan, World War I, college football player[99]

- Joyce Kilmer, World War I, journalist and poet[100]

- Rory Lancman, Cold War, member of the New York State Assembly and New York City Council[101]

- Bruce M. Lawlor, Global War on Terrorism, U.S. Army major general[102]

- George E. Leach, World War I, mayor of Minneapolis[103]

- Michael Joseph Lenihan, World War I, 83rd Brigade commander[104]

- Ralph Linton, World War I, anthropologist[105]

- Charles MacArthur, World War I, author[106]

- Sidney E. Manning, World War I, Medal of Honor[107]

- Jeff W. Mathis III, Cold War, U.S. Army major general[108]

- Moose McCormick, World War I, professional baseball player, director of the United States Army Air Forces during World War II[109]

- Thomas C. Neibaur, World War I, Medal of Honor[110]

- Donald A. Quarles, World War I, United States Deputy Secretary of Defense[111]

- Richard W. O'Neill, World War I, Medal of Honor[112]

- Todd Pillion, Operation Iraqi Freedom, member of the Virginia Senate[113][114]

- B. Carroll Reece, World War I, U.S. congressman[115]

- Henry J. Reilly, World War I, author and journalist[116]

- Louis W. Ross, World War I, architect[117]

- Richard J. Tallman, World War II, U.S. Army brigadier general[118]

- John C. F. Tillson, World War II, U.S. Army major general[119]

- Robert Tyndall, World War I, mayor of Indianapolis[120]

- James Ronald Warren, World War II, Historian[121]

- Emmett Watson, World War I, illustrator[122]

- Arthur Whittemore, World War I, associate justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court[123]

In popular culture

[edit]The soldiers who provide security around the ghost-contaminated apartment building in the 1984 film Ghostbusters wear the uniform of the 42nd Infantry Division.[124] The 42nd Infantry Division was featured in the 2008 monster film Cloverfield.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Special Designation Listing". United States Army Center of Military History. 21 April 2010. Archived from the original on 9 June 2010. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ^ "42nd Infantry Division History". Archived from the original on 22 October 2004. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ Gilbert, Martin (1994). The First World War: a complete history. Henry Hold and Company, Inc., New York. p. 400. ISBN 0-8050-1540-X.

- ^ Duffy, Bernard K.; Carpenter, Ronald H. (1997). Douglas MacArthur: Warrior as Wordsmith. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-313-29148-7.

- ^ James, D. Clayton (1 October 1970). The Years of MacArthur. Vol. 1 (1st ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 146–148. ISBN 978-0-3951-0948-9. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ James, pp. 150–151.

- ^ James, p. 150.

- ^ James, pp. 151–152.

- ^ James, p. 153.

- ^ James, p. 154.

- ^ a b c James, p. 155.

- ^ James, pp. 154–155.

- ^ James, pp. 166, 172.

- ^ James, pp. 159–166.

- ^ Reilly, Henry J. Americans All - The Rainbow at War: Official History of the 42nd Rainbow Division in the World War. Page 880. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015005393957

- ^ a b c d e f 42nd Infantry Division. "Origin of the Rainbow Patch". dmna.ny.gov. Latham, NY: New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Smith, Herbert E. (1935). "A.E.F. Divisional Insignia: 42nd Division". Recruiting News. Governors Island, NY: U.S. Army Recruiting Publicity Bureau. p. 3 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d Watson, Elmo Scott (5 August 1943). "Historic Rainbow Division is Born Anew". The Hope Pioneer. Hope, ND. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Dann, Sam (1998). Dachau 29 April 1945: The Rainbow Liberation Memoirs. Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech University Press. p. ix. ISBN 978-0-8967-2391-7 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Staff Report (27 July 2017). "42nd Infantry "Rainbow" Division to be 100 years old". NJ Today. Rahway, NJ. Archived from the original on 17 August 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ a b Davis, Martin L. (1985). Insignia of the 42nd Rainbow Division. Rainbow Division Veterans Association. pp. 4, 5, 7, 10, 13, 19, 25. ASIN B00071T6W0.

- ^ The Return of Paul Jarrett: Photo Gallery. Los Angeles, CA: Jarrett Entertainment Group. 2001. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ Daly, Hugh C. (1946). "42nd "Rainbow" Infantry Division: A Combat History of World War II". World War Regimental Histories. Baton Rouge, LA: Army and Navy Publishing Company: 177.

- ^ Wilson, John B. (1998). "Chapter VII: The Crucible – Combat". Maneuver and Firepower: The Evolution of Divisions and Separate Brigades. Army Lineage Series. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 60-14. Archived from the original on 26 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Combat Chronicle, 42d Infantry Division". World War II Divisional Combat Chronicles. Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History. 31 January 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ Daly, p. 21.

- ^ Daly, p. 49.

- ^ Dann, Sam (1998). Dachau 29 April 1945: The Rainbow Liberation Memoirs. Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-89672-391-7.

- ^ Epstein, Catherine. (2011). Wzorcowy nazista: Arthur Greiser i okupacja Kraju Warty. Włodarczyk, Jarosław (tłumacz). Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Dolnośląskie. ISBN 978-83-245-9005-6. OCLC 802945568.

- ^ a b c d e Army Battle Casualties and Nonbattle Deaths, Final Report (Statistical and Accounting Branch, Office of the Adjutant General, 1 June 1953)

- ^ a b Wilson, John B. (1998). "Chapter VIII: An Interlude of Peace". Maneuver and Firepower: The Evolution of Divisions and Separate Brigades. Army Lineage Series. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 60-14. Archived from the original on 26 December 2012.

- ^ "Chapter XI: A New Direction – Flexible Response". History.army.mil. Archived from the original on 17 January 2010. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ "Chapter XII: Flexible Response". History.army.mil. Archived from the original on 4 June 2008. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ "42d Infantry "Rainbow" Division" (PDF). State of New York – Division of Military and Naval Affairs. Annual Report 1990: 29–30. 1990. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Casey, George W. Jr. (16 December 2009). "General Orders No. 2009–13" (PDF). Army Publishing Directorate. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Army. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2021 – via Wayback Machine.

- ^ David Zucchino, "Widows pursue justice in soldiers' slayings", Los Angeles Times, 8 April 2010, 15 March 2013

- ^ AUSA, Torchbearer Special Report, 7 November 2005; "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 November 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "27 Infantry Brigade Combat Team". Tioh.hqda.pentagon.mil. 24 August 2007. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ Durr, Eric; Valenza, Andrew (20 October 2018). "NY National Guard Brigade Special Troops Battalion becomes Brigade Engineer Brigade during reflagging ceremony". DVIDS. Washington, DC: Defense Visual Information Distribution Service.

- ^ "Lineage and Honors: Headquarters and Headquarters Company, Combat Aviation Brigade, 42d Infantry Division". Lineages and Honors Information, Divisions and Brigades. U.S. Army Center of Military History. 27 April 2017.

- ^ "Biography, 42d Infantry Division (NY) Commanding General Major General Jack James". dmna.ny.gov. Latham, NY: New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs. Retrieved 24 September 2024.

- ^ Kratzer, Jean (3 February 2024). "NY National Guard senior leader takes command of 42nd Infantry Division". DVIDS. Latham, New York: New York National Guard. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ Guard, National (8 March 2021). "National Guard Thomas Spencer Biography". National Guard. Washington, DC.

- ^ Durr, Eric (3 March 2017). "MG Steven Ferrari takes command of New York National Guard's 42nd Infantry Division". Defense Video Imagery Distribution System (DVIDS). Washington, DC: Defense Media Activity.

- ^ Robidoux, Carol (25 June 2013). "Nashua Resident Becomes Two-Star General: Major General Harry Miller was promoted in a ceremony 24 June at Fort Drum". Nashua Patch. Nashua, NH: Patch.com.

- ^ Sanzo, Rachel (15 April 2013). "Rainbow Division Welcomes New Commander". www.army.mil/. Washington, DC: United States Army.

- ^ Goldenberg, Richard (3 May 2009). "New Leadership For 42nd Infantry Division". New York State Military and Naval Affairs News. Latham, NY: Office of Public Affairs, New York Division of Military and Naval Affairs.

- ^ "New York Adjutant General to Retire". www.army.mil/. Washington, DC: United States Army. 28 January 2010.

- ^ "42nd Infantry Division Welcomes Brigadier General Joseph J. Taluto as Commander". 42nd Infantry Division. Latham, NY: New York Division of Military and Naval Affairs. 6 October 2002.

- ^ New York Red Book. Albany, NY: New York Legal Publishing Corp. 1997. p. 540.

The 42nd Infantry Division with headquarters in Troy, commanded by Brigadier General Thomas D. Kinley.

- ^ New York Red Book. Albany, NY: New York Legal Publishing Corp. 1995. p. 478.

The 42nd Infantry Division with headquarters in Troy, commanded by Major General Robert J. Byrne.

- ^ New York Red Book. Albany, NY: New York Legal Publishing Corp. 1993. p. 527.

The 42nd Infantry Division with headquarters in Troy, commanded by Major General John W. Cudmore.

- ^ New York Red Book. Albany, NY: New York Legal Publishing Corp. 1991. p. 528.

- ^ a b Flynn, Lawrence P. (1988). Annual Report for 1987 (PDF). Latham, NY: New York Division of Military and Naval Affairs. p. 26.

- ^ The Army Quarterly and Defence Journal. Tavistock, England: West of England Press. 1987. p. 216.

- ^ New York Red Book. Albany, NY: New York Legal Publishing Corp. 1988. p. 463.

- ^ Rat, Jacquie (15 December 2005). "Final salute to a hero". Long Island Herald. Garden City, NY.

- ^ Office of Public Affairs (1977). General Officers of the Army and Air National Guard. Washington, DC: National Guard Bureau. p. 232.

- ^ New York Red Book. Albany, NY: New York Legal Publishing Corp. 1975. p. 492.

- ^ "Gen. Baker Commands Rainbow". Times Record. Troy, NY. 31 July 1973. p. 5.

- ^ O'Hara, Almerin C. (1967). "Annual Report for the Division of Military and Naval Affairs" (PDF). New York Division of Military and Naval Affairs. Albany, NY: Williams Press. p. 22.

- ^ O'Hara, Almerin C. (1964). "Annual Report for the Division of Military and Naval Affairs" (PDF). New York Division of Military and Naval Affairs. Albany, NY: Williams Press. p. 17.

- ^ Hausauer, Karl (1951). "Annual Report for the Division of Military and Naval Affairs" (PDF). New York Division of Military and Naval Affairs. Albany, NY: Williams Press. p. 6.

- ^ "Commander Retires". Kingston Daily Freeman. Kingston, NY. Associated Press. 4 September 1948. p. 12.

- ^ Daly, p. 2.

- ^ a b Rinaldi, Richard A. (2005). The US Army in World War I: Orders of Battle. Takoma Park, MD: General Data LLC. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-9720296-4-3.

- ^ Association of Graduates of the United States Military Academy (1922). Annual Report. Saginaw, MI: Seeman & Peters. p. 32.

- ^ MacArthur, Douglas (24 January 1964). "How the 'Citizen Soldiers' Defeated the Germans". LIFE Magazine. New York, NY: Time Inc.: 81.

- ^ Persico, Joseph E. (2005). Eleventh Month, Eleventh Day, Eleventh Hour: Armistice Day, 1918 World War I and its Violent Climax. New York, NY: Random House. p. 332. ISBN 978-0-375-76045-7.

- ^ Whigham, H. J. (1 March 1919). "About People We Know: Menoher Upon MacArthur". Town and Country. New York, NY: The Stuyvesant Company: 20.

- ^ Johnson, Harold Stanley (1917). Roster of the Rainbow division (forty-second) Major General Wm. A. Mann, Commanding. New York, NY: Eaton & Gettinger. p. 10.

- ^ "Veteran Of The Day: Army Veteran Vito Bertoldo". VAntage Point. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. 20 May 2021.

- ^ "YLS Mourns Death of Boris I. Bittker; Memorial Service Scheduled Dec. 11". Yale Law School News. New haven, CT: Yale Law School. 12 September 2005.

- ^ Health Sciences Library, Columbia University. "Biographical Note, George E. Brewer". George Emerson Brewer scrapbook, 1903, 1913-1923 (bulk 1917-1919). New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ "Joe Brooks, All-American Tackle, Kills Himself". New York Daily News. New York, NY. 28 November 1953. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Person Record, Wilber Marion Brucker". Detroit Historical Society 100. Detroit, MI: Detroit Historical Society. 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ Bolkcom, Joe; Dvorsky, Robert E.; Fiegen, Thomas L. (2001). "Biography, Senator Robert J. Burns". The Iowa Legislature. Des Moines, IA: Iowa Senate. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ Historical Section, Army War College (1931). Order of Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 272 – via Google Books.

- ^ Fergusson, Peter J. (1985). "Necrology, Kenneth John Conant (1895-1984)". Gesta. 24 (1). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press: 87. doi:10.1086/ges.24.1.766935. S2CID 192104410. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ "Cpt. Corbett and Carroll Hurlburt Both in New York". The Oregon Journal. Portland, OR. 13 June 1919. p. 21 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Obituary: Services Conducted for Hamilton F. Corbett". The Oregon Journal. Portland, OR. 9 May 1966. p. 6 – via GenealogyBank.com.

- ^

"Scott Corbett dies, author and educator". Archived from the original on 17 April 2008. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). John Monaghan. The Providence Journal. March 9, 2006. Archived 2008-04-17. Retrieved 2013-06-28. - ^ Weer, William (6 May 1934). "Cunningham Was World War Hero". Brooklyn Eagle. Brooklyn, NY. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Coughlin, William P. (2 June 1986). "Roger Cutler Jr., 70, of Needham; was lawyer, banker and Olympian". The Boston Globe. Boston, MA. p. 43 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Exiles Name DeLacour to membership". Hartford Courant. Hartford, CT. 25 December 1947. p. 23 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Runyon, Damon (27 November 1942). "The Brighter Side". Idaho Statesman. Boise, ID. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Morahan, Thomas P. (28 May 2010). "Michael A. Donaldson, Veterans' Hall of Fame". NY Senate.gov. Albany, NY: New York State Senate. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ Balestrieri, Steve (15 October 2018). "William "Wild Bill" Donovan OSS, Awarded the Medal of Honor in WWI". Special Operations Forces Report (SOFREP). Incline Village, NV. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ Goldenberg, Richard (29 June 2018). "Fighting Father Duffy remembered fondly in New York City". National Guard.mil. Arlington, VA.

- ^ Senior Leader Management Office (24 November 2020). "Biography, Francis J. Evon, Jr". National Guard.mil. Arlington, VA: National Guard Bureau. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ Mitchell, H. W. (1920). "Report of the Committee on War Work". Proceedings of the American Medico-Psychological Association. Philadelphia, PA: American Medico-Psychological Association. p. 353 – via Google Books.

- ^ Director's Booklet (PDF). New York, NY: American Airlines. 5 May 1943. p. 1.

- ^ Treaster, Joseph B. (17 April 1082). "Gen. Thomas T. Handy Dies; Was Deputy for Eisenhower". The New York Times. New York, NY. p. 15.

- ^ "Rainbow Division Veterans to Help Start New One". Kilgore News Herald. Kilgore, TX. United Press. 12 July 1943. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Office of Governor Phil Murphy (3 May 2021). "Governor Murphy Nominates Colonel Dr. Lisa Hou as Adjutant General and Commissioner of the New Jersey Department of Military and Veterans Affairs". NJ.gov. Trenton, NJ. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ "Biography, Benson Walker Hough". Supreme Court.Ohio.gov. Columbus, OH: Supreme Court of Ohio and Ohio Judicial Center. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ Zedalis, Joe (12 July 2004). "War not far away at open house". Asbury Park Press. Asbury Park, NJ. pp. B1–B2.

- ^ Simon, Bryant (8 June 2016). "Biography, Olin DeWitt Talmadge Johnston". South Carolina Encyclopedia. Charleston, SC: University of South Carolina. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ Little, Bill (26 May 2014). "Biography, Louis Jordan". The History of Longhorn Sports. Austin, TX: Texas Legacy Support Network. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ Tupper, Ben (17 May 2011). "Close to the Heart". Army.mil. Washington, DC: U.S. Army. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ Rose, Naeisha (8 May 2019). "Queens Councilman Wants to Protect Homeowners, Tenants as District Attorney". Politics NY. Bayside, NY: Political Edge LLC. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ Senior Leader Management Office (30 April 2001). "General Officer Biography, Bruce M. Lawlor". National Guard.mil. Arlington, VA: National Guard Bureau. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ Minnesota Military Museum (14 January 2015). "Major General George E. Leach (1876-1955), A Featured Veteran from Minneapolis, Minnesota" (PDF). MN Military Museum.org. Camp Ripley, MN: Military Historical Society of Minnesota. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ Bill, Thayer (2016). "Michael Joseph Lenihan". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Kluckhohn, Clyde (1958). Ralph Linton, 1893–1953: A Biographical Memoir (PDF). Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences. p. 238.

- ^ "Reporter Writes View of the War". The Fourth Estate. New York, NY. 20 December 1919. p. 25.

- ^ Neeley, Graham R. (31 May 2017). "Sidney Earnest Manning". The Encyclopedia of Alabama. Birmingham, AL: Alabama Humanities Alliance.

- ^ Senior Leader Management Office (31 October 2014). "General Officer Biography, Jeff W. Mathis III". National Guard.mil. Arlington, VA: National Guard Bureau. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ^ Karmik, Thom (25 January 2016). ""Soldiers 'Over There' Sore on Baseball Players"". Baseball History Daily. Chicago, IL. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ Robison, Heath (2022). "Biography, Thomas Croft Neibauer". Idaho Heroes.org. Boise, ID. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ "National Affairs: New Air Force Boss". TIME. New York, NY: Time Inc. 22 August 1955.

- ^ "Richard W. O'Neill, 84, Dies; A Winner of Medal of Honor". The New York Times. New York, NY. 11 April 1982. p. 34.

- ^ "Member Spotlight: Todd Pillion". Virginia House GOP. Richmond, VA: House Republican Campaign Committee, Inc. 11 July 2016.

- ^ Marais, Bianca (5 November 2019). "Todd Pillion defeats Heath for Virginia Senate District 40 seat". WJHL-TV. Johnson City, TN.

- ^ Bowers, F. Suzanne (2010). Republican, First, Last, and Always: A Biography of B. Carroll Reece. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 12–14. Archived from the original on 8 February 2015.

- ^ Mahon, John (2004). New York's Fighting Sixty-Ninth. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-7864-6104-2 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Louis W. Ross, Architect, Dies; Rites Saturday". The Boston Globe. Boston, MA. 9 September 1966. p. 33 – via Google Books.

- ^ "New Position for Tallman". The Scrantonian. Scranton, PA. 27 April 1969. p. 23 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ 25th Infantry Division (6 March 1967). "Gen. Weyand Leaves 25th Division: Gen. Tillson Commands". Tropic Lightning News. Củ Chi Base Camp, Vietnam. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Jones, Thomas (15 September 2014). "Remembering a Veteran: Col. Robert Tyndall of Indiana and the Rainbow Division". Roads to the Great War. Michael E. Hanlon. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ "Book Review: The War Years: A Chronicle of Washington State in World War II". Washington State Magazine. Pullman, WA: Washington State University. 2000. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ "Joyce Kilmer's Death Related in Papers Displayed at Columbia". Central New jersey Home News. New Brunswick, NJ. 31 July 1961. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court (1971). "Associate Justice Memorial, Arthur Easterbrook Whittemore". Massachusetts Court System. Boston, MA: Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ 1humanguy at YouTube (4 December 2013). Ghostbusters: Saving the Day. Event occurs at 1:57. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

Sources

[edit]- The Army Almanac: A Book of Facts Concerning the Army of the United States Archived 21 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Government Printing Office, 1950 reproduced at the United States Army Center of Military History.

- James J. Cooke, The Rainbow Division in the Great War, 1917–1919, Greenwood Publishing Group, Incorporated 1994 ISBN 0-275-94768-8

- Thompson, Robert (2023). Approach to Final Victory: America's Rainbow Division in the Saint Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne Offensives. Westholme Publishing. ISBN 978-1594164095.

External links

[edit]- 42nd Division homepage

- Rosedale Arch dedicated to the Rainbow Division in WWI

- Rainbow Memories; Character Sketches of the 1st Battalion 166th Infantry Regiment

- www.historynet.com – 42nd Division in Alsace

- www.lonesentry.com – 42nd Division history

- The short film Big Picture: 42nd Rainbow Division is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- Infantry divisions of the United States Army

- United States Army divisions during World War II

- Divisions of the United States Army National Guard

- United States Army divisions of World War I

- Infantry divisions of the United States Army in World War II

- Military units and formations in New York (state)

- Military units and formations established in 1917

- Military units and formations in Massachusetts