Multiply perfect number

In mathematics, a multiply perfect number (also called multiperfect number or pluperfect number) is a generalization of a perfect number.

For a given natural number k, a number n is called k-perfect (or k-fold perfect) if the sum of all positive divisors of n (the divisor function, σ(n)) is equal to kn; a number is thus perfect if and only if it is 2-perfect. A number that is k-perfect for a certain k is called a multiply perfect number. As of 2014, k-perfect numbers are known for each value of k up to 11.[1]

It is unknown whether there are any odd multiply perfect numbers other than 1. The first few multiply perfect numbers are:

- 1, 6, 28, 120, 496, 672, 8128, 30240, 32760, 523776, 2178540, 23569920, 33550336, 45532800, 142990848, 459818240, ... (sequence A007691 in the OEIS).

Example

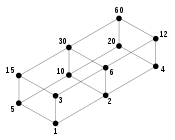

[edit]The sum of the divisors of 120 is

- 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6 + 8 + 10 + 12 + 15 + 20 + 24 + 30 + 40 + 60 + 120 = 360

which is 3 × 120. Therefore 120 is a 3-perfect number.

Smallest known k-perfect numbers

[edit]The following table gives an overview of the smallest known k-perfect numbers for k ≤ 11 (sequence A007539 in the OEIS):

| k | Smallest k-perfect number | Factors | Found by |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | ancient | |

| 2 | 6 | 2 × 3 | ancient |

| 3 | 120 | 23 × 3 × 5 | ancient |

| 4 | 30240 | 25 × 33 × 5 × 7 | René Descartes, circa 1638 |

| 5 | 14182439040 | 27 × 34 × 5 × 7 × 112 × 17 × 19 | René Descartes, circa 1638 |

| 6 | 154345556085770649600 (21 digits) | 215 × 35 × 52 × 72 × 11 × 13 × 17 × 19 × 31 × 43 × 257 | Robert Daniel Carmichael, 1907 |

| 7 | 141310897947438348259849...523264343544818565120000 (57 digits) | 232 × 311 × 54 × 75 × 112 × 132 × 17 × 193 × 23 × 31 × 37 × 43 × 61 × 71 × 73 × 89 × 181 × 2141 × 599479 | TE Mason, 1911 |

| 8 | 826809968707776137289924...057256213348352000000000 (133 digits) | 262 × 315 × 59 × 77 × 113 × 133 × 172 × 19 × 23 × 29 × 312 × 37 × 41 × 43 × 53 × 612 × 712 × 73 × 83 × 89 × 972 × 127 × 193 × 283 × 307 × 317 × 331 × 337 × 487 × 5212 × 601 × 1201 × 1279 × 2557 × 3169 × 5113 × 92737 × 649657 | Stephen F. Gretton, 1990[1] |

| 9 | 561308081837371589999987...415685343739904000000000 (287 digits) | 2104 × 343 × 59 × 712 × 116 × 134 × 17 × 194 × 232 × 29 × 314 × 373 × 412 × 432 × 472 × 53 × 59 × 61 × 67 × 713 × 73 × 792 × 83 × 89 × 97 × 1032 × 107 × 127 × 1312 × 1372 × 1512 × 191 × 211 × 241 × 331 × 337 × 431 × 521 × 547 × 631 × 661 × 683 × 709 × 911 × 1093 × 1301 × 1723 × 2521 × 3067 × 3571 × 3851 × 5501 × 6829 × 6911 × 8647 × 17293 × 17351 × 29191 × 30941 × 45319 × 106681 × 110563 × 122921 × 152041 × 570461 × 16148168401 | Fred Helenius, 1995[1] |

| 10 | 448565429898310924320164...000000000000000000000000 (639 digits) | 2175 × 369 × 529 × 718 × 1119 × 138 × 179 × 197 × 239 × 293 × 318 × 372 × 414 × 434 × 474 × 533 × 59 × 615 × 674 × 714 × 732 × 79 × 83 × 89 × 97 × 1013 × 1032 × 1072 × 109 × 113 × 1272 × 1312 × 139 × 149 × 151 × 163 × 179 × 1812 × 191 × 197 × 199 × 2113 × 223 × 239 × 257 × 271 × 281 × 307 × 331 × 337 × 3532 × 367 × 373 × 397 × 419 × 421 × 521 × 523 × 5472 × 613 × 683 × 761 × 827 × 971 × 991 × 1093 × 1741 × 1801 × 2113 × 2221 × 2237 × 2437 × 2551 × 2851 × 3221 × 3571 × 3637 × 3833 × 4339 × 5101 × 5419 × 6577 × 6709 × 7621 × 7699 × 8269 × 8647 × 11093 × 13421 × 13441 × 14621 × 17293 × 26417 × 26881 × 31723 × 44371 × 81343 × 88741 × 114577 × 160967 × 189799 × 229153 × 292561 × 579281 × 581173 × 583367 × 1609669 × 3500201 × 119782433 × 212601841 × 2664097031 × 2931542417 × 43872038849 × 374857981681 × 4534166740403 | George Woltman, 2013[1] |

| 11 | 251850413483992918774837...000000000000000000000000 (1907 digits) | 2468 × 3140 × 566 × 749 × 1140 × 1331 × 1711 × 1912 × 239 × 297 × 3111 × 378 × 415 × 433 × 473 × 534 × 593 × 612 × 674 × 714 × 733 × 79 × 832 × 89 × 974 × 1014 × 1033 × 1093 × 1132 × 1273 × 1313 × 1372 × 1392 × 1492 × 151 × 1572 × 163 × 167 × 173 × 181 × 191 × 1932 × 197 × 199 × 2113 × 223 × 227 × 2292 × 239 × 251 × 257 × 263 × 2693 × 271 × 2812 × 293 × 3073 × 313 × 317 × 331 × 347 × 349 × 367 × 373 × 397 × 401 × 419 × 421 × 431 × 4432 × 449 × 457 × 461 × 467 × 491 × 4992 × 541 × 547 × 569 × 571 × 599 × 607 × 613 × 647 × 691 × 701 × 719 × 727 × 761 × 827 × 853 × 937 × 967 × 991 × 997 × 1013 × 1061 × 1087 × 1171 × 1213 × 1223 × 1231 × 1279 × 1381 × 1399 × 1433 × 1609 × 1613 × 1619 × 1723 × 1741 × 1783 × 1873 × 1933 × 1979 × 2081 × 2089 × 2221 × 2357 × 2551 × 2657 × 2671 × 2749 × 2791 × 2801 × 2803 × 3331 × 3433 × 4051 × 4177 × 4231 × 5581 × 5653 × 5839 × 6661 × 7237 × 7699 × 8081 × 8101 × 8269 × 8581 × 8941 × 10501 × 11833 × 12583 × 12941 × 13441 × 14281 × 15053 × 17929 × 19181 × 20809 × 21997 × 23063 × 23971 × 26399 × 26881 × 27061 × 28099 × 29251 × 32051 × 32059 × 32323 × 33347 × 33637 × 36373 × 38197 × 41617 × 51853 × 62011 × 67927 × 73547 × 77081 × 83233 × 92251 × 93253 × 124021 × 133387 × 141311 × 175433 × 248041 × 256471 × 262321 × 292561 × 338753 × 353641 × 441281 × 449653 × 509221 × 511801 × 540079 × 639083 × 696607 × 746023 × 922561 × 1095551 × 1401943 × 1412753 × 1428127 × 1984327 × 2556331 × 5112661 × 5714803 × 7450297 × 8334721 × 10715147 × 14091139 × 14092193 × 18739907 × 19270249 × 29866451 × 96656723 × 133338869 × 193707721 × 283763713 × 407865361 × 700116563 × 795217607 × 3035864933 × 3336809191 × 35061928679 × 143881112839 × 161969595577 × 287762225677 × 761838257287 × 840139875599 × 2031161085853 × 2454335007529 × 2765759031089 × 31280679788951 × 75364676329903 × 901563572369231 × 2169378653672701 × 4764764439424783 × 70321958644800017 × 79787519018560501 × 702022478271339803 × 1839633098314450447 × 165301473942399079669 × 604088623657497125653141 × 160014034995323841360748039 × 25922273669242462300441182317 × 15428152323948966909689390436420781 × 420391294797275951862132367930818883361 × 23735410086474640244277823338130677687887 × 628683935022908831926019116410056880219316806841500141982334538232031397827230330241 | George Woltman, 2001[1] |

Properties

[edit]It can be proven that:

- For a given prime number p, if n is p-perfect and p does not divide n, then pn is (p + 1)-perfect. This implies that an integer n is a 3-perfect number divisible by 2 but not by 4, if and only if n/2 is an odd perfect number, of which none are known.

- If 3n is 4k-perfect and 3 does not divide n, then n is 3k-perfect.

Odd multiply perfect numbers

[edit]It is unknown whether there are any odd multiply perfect numbers other than 1. However if an odd k-perfect number n exists where k > 2, then it must satisfy the following conditions:[2]

- The largest prime factor is ≥ 100129

- The second largest prime factor is ≥ 1009

- The third largest prime factor is ≥ 101

Bounds

[edit]In little-o notation, the number of multiply perfect numbers less than x is for all ε > 0.[2]

The number of k-perfect numbers n for n ≤ x is less than , where c and c' are constants independent of k.[2]

Under the assumption of the Riemann hypothesis, the following inequality is true for all k-perfect numbers n, where k > 3

where is Euler's gamma constant. This can be proven using Robin's theorem.

The number of divisors τ(n) of a k-perfect number n satisfies the inequality[3]

The number of distinct prime factors ω(n) of n satisfies[4]

If the distinct prime factors of n are , then:[4]

Specific values of k

[edit]Perfect numbers

[edit]A number n with σ(n) = 2n is perfect.

Triperfect numbers

[edit]A number n with σ(n) = 3n is triperfect. There are only six known triperfect numbers and these are believed to comprise all such numbers:

If there exists an odd perfect number m (a famous open problem) then 2m would be 3-perfect, since σ(2m) = σ(2) σ(m) = 3×2m. An odd triperfect number must be a square number exceeding 1070 and have at least 12 distinct prime factors, the largest exceeding 105.[5]

Variations

[edit]Unitary multiply perfect numbers

[edit]A similar extension can be made for unitary perfect numbers. A positive integer n is called a unitary multi k-perfect number if σ*(n) = kn where σ*(n) is the sum of its unitary divisors. (A divisor d of a number n is a unitary divisor if d and n/d share no common factors.).

A unitary multiply perfect number is simply a unitary multi k-perfect number for some positive integer k. Equivalently, unitary multiply perfect numbers are those n for which n divides σ*(n). A unitary multi 2-perfect number is naturally called a unitary perfect number. In the case k > 2, no example of a unitary multi k-perfect number is yet known. It is known that if such a number exists, it must be even and greater than 10102 and must have more than forty four odd prime factors. This problem is probably very difficult to settle. The concept of unitary divisor was originally due to R. Vaidyanathaswamy (1931) who called such a divisor as block factor. The present terminology is due to E. Cohen (1960).

The first few unitary multiply perfect numbers are:

Bi-unitary multiply perfect numbers

[edit]A positive integer n is called a bi-unitary multi k-perfect number if σ**(n) = kn where σ**(n) is the sum of its bi-unitary divisors. This concept is due to Peter Hagis (1987). A bi-unitary multiply perfect number is simply a bi-unitary multi k-perfect number for some positive integer k. Equivalently, bi-unitary multiply perfect numbers are those n for which n divides σ**(n). A bi-unitary multi 2-perfect number is naturally called a bi-unitary perfect number, and a bi-unitary multi 3-perfect number is called a bi-unitary triperfect number.

A divisor d of a positive integer n is called a bi-unitary divisor of n if the greatest common unitary divisor (gcud) of d and n/d equals 1. This concept is due to D. Surynarayana (1972). The sum of the (positive) bi-unitary divisors of n is denoted by σ**(n).

Peter Hagis (1987) proved that there are no odd bi-unitary multiperfect numbers other than 1. Haukkanen and Sitaramaiah (2020) found all bi-unitary triperfect numbers of the form 2au where 1 ≤ a ≤ 6 and u is odd,[6][7][8] and partially the case where a = 7.[9] [10] Further, they fixed completely the case a = 8.[11]

The first few bi-unitary multiply perfect numbers are:

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Flammenkamp, Achim. "The Multiply Perfect Numbers Page". Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ^ a b c Sándor, Mitrinović & Crstici 2006, p. 105

- ^ Dagal, Keneth Adrian P. (2013). "A Lower Bound for τ(n) for k-Multiperfect Number". arXiv:1309.3527 [math.NT].

- ^ a b Sándor, Mitrinović & Crstici 2006, p. 106

- ^ Sándor, Mitrinović & Crstici 2006, pp. 108–109

- ^ Haukkanen & Sitaramaiah 2020a

- ^ Haukkanen & Sitaramaiah 2020b

- ^ Haukkanen & Sitaramaiah 2020c

- ^ Haukkanen & Sitaramaiah 2020d

- ^ Haukkanen & Sitaramaiah 2021a

- ^ Haukkanen & Sitaramaiah 2021b

Sources

[edit]- Broughan, Kevin A.; Zhou, Qizhi (2008). "Odd multiperfect numbers of abundancy 4" (PDF). Journal of Number Theory. 126 (6): 1566–1575. doi:10.1016/j.jnt.2007.02.001. hdl:10289/1796. MR 2419178.

- Guy, Richard K. (2004). Unsolved problems in number theory (3rd ed.). Springer-Verlag. B2. ISBN 978-0-387-20860-2. Zbl 1058.11001.

- Haukkanen, Pentti; Sitaramaiah, V. (2020a). "Bi-unitary multiperfect numbers, I" (PDF). Notes on Number Theory and Discrete Mathematics. 26 (1): 93–171. doi:10.7546/nntdm.2020.26.1.93-171.

- Haukkanen, Pentti; Sitaramaiah, V. (2020b). "Bi-unitary multiperfect numbers, II" (PDF). Notes on Number Theory and Discrete Mathematics. 26 (2): 1–26. doi:10.7546/nntdm.2020.26.2.1-26.

- Haukkanen, Pentti; Sitaramaiah, V. (2020c). "Bi-unitary multiperfect numbers, III" (PDF). Notes on Number Theory and Discrete Mathematics. 26 (3): 33–67. doi:10.7546/nntdm.2020.26.3.33-67.

- Haukkanen, Pentti; Sitaramaiah, V. (2020d). "Bi-unitary multiperfect numbers, IV(a)" (PDF). Notes on Number Theory and Discrete Mathematics. 26 (4): 2–32. doi:10.7546/nntdm.2020.26.4.2-32.

- Haukkanen, Pentti; Sitaramaiah, V. (2021a). "Bi-unitary multiperfect numbers, IV(b)" (PDF). Notes on Number Theory and Discrete Mathematics. 27 (1): 45–69. doi:10.7546/nntdm.2021.27.1.45-69.

- Haukkanen, Pentti; Sitaramaiah, V. (2021b). "Bi-unitary multiperfect numbers, V" (PDF). Notes on Number Theory and Discrete Mathematics. 27 (2): 20–40. doi:10.7546/nntdm.2021.27.2.20-40.

- Kishore, Masao (1987). "Odd triperfect numbers are divisible by twelve distinct prime factors". Journal of the Australian Mathematical Society, Series A. 42 (2): 173–182. doi:10.1017/s1446788700028184. ISSN 0263-6115. Zbl 0612.10006.

- Laatsch, Richard (1986). "Measuring the abundancy of integers". Mathematics Magazine. 59 (2): 84–92. doi:10.2307/2690424. ISSN 0025-570X. JSTOR 2690424. MR 0835144. Zbl 0601.10003.

- Merickel, James G. (1999). "Divisors of Sums of Divisors: 10617". The American Mathematical Monthly. 106 (7): 693. doi:10.2307/2589515. JSTOR 2589515. MR 1543520.

- Ryan, Richard F. (2003). "A simpler dense proof regarding the abundancy index". Mathematics Magazine. 76 (4): 299–301. doi:10.1080/0025570X.2003.11953197. JSTOR 3219086. MR 1573698. S2CID 120960379.

- Sándor, Jozsef; Crstici, Borislav, eds. (2004). Handbook of number theory II. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic. pp. 32–36. ISBN 1-4020-2546-7. Zbl 1079.11001.

- Sándor, József; Mitrinović, Dragoslav S.; Crstici, Borislav, eds. (2006). Handbook of number theory I. Dordrecht: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 1-4020-4215-9. Zbl 1151.11300.

- Sorli, Ronald M. (2003). Algorithms in the study of multiperfect and odd perfect numbers (PhD thesis). Sydney: University of Technology. hdl:10453/20034.

- Weiner, Paul A. (2000). "The abundancy ratio, a measure of perfection". Mathematics Magazine. 73 (4): 307–310. doi:10.1080/0025570x.2000.11996860. JSTOR 2690980. MR 1573474. S2CID 119773896.

![{\displaystyle r\left({\sqrt[{r}]{3/2}}-1\right)<\sum _{i=1}^{r}{\frac {1}{p_{i}}}<r\left(1-{\sqrt[{r}]{6/k^{2}}}\right),~~{\text{if }}n{\text{ is even}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/413cf0a0d2e58457c15f88760e2022db99e6660c)

![{\displaystyle r\left({\sqrt[{3r}]{k^{2}}}-1\right)<\sum _{i=1}^{r}{\frac {1}{p_{i}}}<r\left(1-{\sqrt[{r}]{8/(k\pi ^{2})}}\right),~~{\text{if }}n{\text{ is odd}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a14ab363496c148721680c431a26a3db3dfc267a)