Boarstall

| Boarstall | |

|---|---|

Boarstall Tower | |

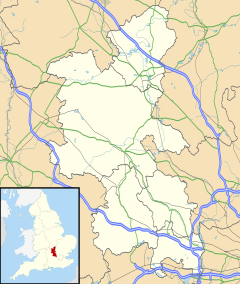

Location within Buckinghamshire | |

| Population | 128 (2011 Census)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SP6214 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Aylesbury |

| Postcode district | HP18 |

| Dialling code | 01844 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Buckinghamshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | Boarstall.com |

Boarstall is a village and civil parish in the Aylesbury Vale district of Buckinghamshire, about 12 miles (19 km) west of Aylesbury. The parish is on the county boundary with Oxfordshire and the village is about 5.5 miles (9 km) southeast of the Oxfordshire market town of Bicester.

Etymology

[edit]The name Boarstall is first attested in 1158–59 as Burchestala. This derives from the Old English words burh ("fortification, town") and steall ("settlement, location, site"). Thus it once meant "site of the fort".[2]

The parish also contains Panshill Farm, whose name is first attested in the thirteenth century in the forms Pansehale, Pauncehale, Pauncehaye, and Paunsehale. The name is noted as a likely example of an etymologically Brittonic English place-name. It is thought to derive from the words that survive in modern Welsh as penn ("head, end, top, peak") and coed ("wood").[3][4]: 278

History

[edit]According to legend King Edward the Confessor gave some land to one of his men in return for slaying a wild boar that had infested the nearby Bernwood Forest.[5] The man built himself a mansion on this land and called it "Boar-stall" (Old English for 'Boar House') in memory of the slain beast. The man, known as Neil, was also given a horn from the dead beast, and the legend says that whoever shall possess the horn shall be the lord of the manor of Boarstall.[5][6]

It is certainly the case from manorial records of 1265 that the owner of the manor of Boarstall was the ceremonial keeper of the Bernwood Forest, suggesting a link with the earlier legend. Given the proximity of Boarstall to the king's palace at Brill it would appear that this legend certainly has some basis in fact.[5]

The Magna Britannia of 1806 noted that the current incumbent of the manor, Sir John Aubrey, was in possession of a large horn

"of a dark brown colour, variegated and veined like tortoise-shell. It is two feet four inches in length, on the convex bend, the diameter of the larger end is three inches; at each end it is tipt with silver, gilt, and has a wreath of leather, by which it is hung about the neck".[6]

The manor was fortified in 1312 by the construction of a defensive gatehouse. The house was demolished in 1778 but the gatehouse, very large and grand for its time, survives relatively unaltered. Boarstall Tower, which was originally part of the 18th century house on the site, was given to the National Trust by the philanthropist Ernest Cook, founder of the Ernest Cook Trust. In the English Civil War this was made into a garrison by King Charles I who was in possession of the nearby village of Brill. When Brill fell in 1643, so did the garrison at Boarstall. However whereas the manor at Brill was destroyed in the fighting, the fortified manor at Boarstall was saved, and used as a garrison by John Hampden's men, from which they were able to attack Royalist Oxford, 8 miles (13 km) away.[6]

Having no further use for the manor in 1644, Hampden left to go and fight elsewhere. The house was then taken back for the Royalists by Colonel Henry Gage, who it is said launched such heavy fire from his cannons against the house that the incumbent Penelope, Lady Dynham was forced to evacuate and steal away in disguise. Gage left a small garrison in place to defend the house.[6]

In May 1645 the house was attacked again by the Parliamentarian forces, this time led by Sir Thomas Fairfax, but he was unsuccessful. The following year in 1646 Fairfax returned, and the house was surrendered to him on 10 June, after a siege of 18 hours.

Ecclesiastically, Boarstall was originally a chapel of ease for nearby Oakley, and its tithes were granted by Empress Matilda to St Frideswide's Priory in Oxford. The ecclesiastical parish of Boarstall was formed in 1418. The original parish church was mainly demolished in the English Civil War but a replacement was constructed out of funds provided by Lady Denham.[5][6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Key Figures for 2011 Census: Key Statistics". Neighbourhood Statistics: 2011 census. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ Watts, Victor, ed. (2004). The Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names, Based on the Collections of the English Place-Name Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521168557., s.v. Boarstall.

- ^ Baker, John T., Cultural Transition in the Chilterns and Essex Region, 350 AD to 650 AD, University of Hertford Press Studies in Regional and Local History, 4 (Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press, 2006), p. 149.

- ^ Coates, Richard; Breeze, Andrew (2000). Celtic Voices, English Places: Studies of the Celtic Impact on Place-Names in Britain. Stamford: Tyas. ISBN 1900289415..

- ^ a b c d Page, William, ed. (1 January 1927). "'Parishes : Boarstall'". A History of the County of Buckingham. Vol. 4. pp. 9–14. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Lysons, Samuel (1806). Magna Britannia;: being a concise topographical account of the several counties of Great Britain. Vol. 1 (Bedfordshire Berkshire and Buckinghamshire). T. Cadell and W. Davies.

Further reading

[edit]- Lysons, Daniel; Lysons, Samuel (1806). Magna Britannia: being a concise topographical account of the several counties of Great Britain. Vol. 1. Containing Bedfordshire, Berkshire, and Buckinghamshire.

- Page, W.H., ed. (1927). A History of the County of Buckingham, Volume 4. Victoria County History.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1973) [1966]. Buckinghamshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 68–69. ISBN 0-14-071019-1.

- Reed, Michael (1979). Hoskins, W.G.; Millward, Roy (eds.). The Buckinghamshire Landscape. The Making of the English Landscape. London: Hodder & Stoughton. pp. 41, 74, 81, 118, 121, 122, 127, 135, 195–197. ISBN 0-340-19044-2.