Pierre Gringore

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2009) |

| French and Francophone literature |

|---|

| by category |

| History |

| Movements |

| Writers |

| Countries and regions |

| Portals |

Pierre Gringore | |

|---|---|

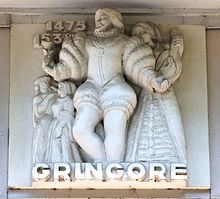

Representation of Pierre Gringore on the hotel Malherbe at Caen | |

| Born | 1470 or 1475 |

| Died | 1539 |

| Occupation(s) | poet and playwright |

| Spouse | Catherine Roger |

Pierre Gringore (French pronunciation: [pjɛʁ ɡʁɛ̃ɡɔʁ]; 1475? – 1538) was a popular French poet and playwright.[1]

Biography

[edit]Pierre Gringore was born in Normandy, at Thury-Harcourt, but the exact date and place of his death are unknown. His first work was Le Chasteau de Labour (1499), an allegorical poem.

His birth name, that Pierre Gringore himself chose to modify, was Gringon.

From 1506 to 1512, he worked as an actor-manager and playwright in Paris. He is best known for the satirical plays he wrote during this period for the Confrérie des Enfants Sans Souci or Sots, a famous comedic acting troupe. While in Paris he became a favorite of Louis XII, who employed the troupe to poke fun at the papacy. Tension between France and Rome was building during this period, eventually resulting in the Italian Wars and the formation of the Catholic League in 1511. Gringore wrote several scathing indictments of Pope Julius II, for example, La Chasse du cerf des cerfs (1510) and the trilogy Le Jeu du Prince des Sots et Mère Sotte.

Following his Parisian period, he wrote a mystery play about Louis IX, Vie Monseigneur Sainct Loys par personnaiges (1514), for the Paris guild of masons and carpenters. Some scholars consider this to be his masterpiece.

Personal life

[edit]After Francis I took the throne, he put severe restrictions on plays and playwrights in place. Gringore moved to Lorraine in 1518, where he married Catherine Roger.

Religion

[edit]Despite the various works in which he attacked the papacy, Gringore was a devout Catholic. One of his later works, Blazon des hérétiques (1524), attacks heretics and leaders of the Protestant Reformation, up to and including Martin Luther.

In popular culture

[edit]The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

[edit]A loosely fictionalized vision of Gringoire appears as an important character in Victor Hugo's novel The Hunchback of Notre-Dame and films based on it, except the 1996 animated Disney film (in which his character is combined with Captain Phoebus) and its 2002 direct-to-video sequel. He is probably best known from Hugo's book, in which he was inspired by and bears some resemblance to the historical Gringoire.[2]

In Victor Hugo's original novel

[edit]

During the Feast of Fools, which is when the story begins, a crowd of people arrive at the Grand Hall of the Palace of Justice where Gringoire introduces them to a play written by him, but is soon interrupted by Clopin Trouillefou, the King of Truands. When the crowd leaves the play and celebrate the crowning of Quasimodo as the Pope of Fools, Gringoire feels disappointed. Later, when he sees Esmeralda dancing near the fire, he forgets about his failed play and falls in love with her.

Later that night, Gringoire follows Esmeralda walking until he witnesses Quasimodo attempting to kidnap her under Archdeacon Claude Frollo's orders, followed by her being saved and the hunchback being captured by Captain Phoebus and his guards. Later, he sees some Truands come toward him and accidentally trespasses into the Court of Miracles, the home of the Truands. Clopin accuses him of entering the Court without permission, and gives him a test in order to save his life: to take a purse from the pocket of a suspended dummy hung all over with tiny bells without making the bells sound. When Gringoire fails the test, he is about to be hanged under Clopin's orders until Clopin gives him another option to save his life: to marry a Roma woman present in the Court. Esmeralda comes to Gringoire's rescue and accepts him as her husband.

Afterwards, Gringoire and Esmeralda have a wedding night together, during which he finds out that Esmeralda doesn't truly love him and merely tolerates him, and that he cannot touch her ever. In fact, the one whom Esmeralda truly loves is Captain Phoebus. Likewise, Gringoire becomes more fond of Esmeralda's pet goat, Djali, than of Esmeralda herself.

Later in the story, Gringoire breaks into the cathedral and rescues Esmeralda along with Frollo, whose identity is hidden behind a cloak. The trio leaves Notre Dame by boat to look for safety from the guards who are after Esmeralda. When the trio hear the voice of a guard, Gringoire abandons Esmeralda and instead saves her goat Djali, resulting in Frollo's capturing Esmeralda and her death. At the end of the story, Gringoire becomes a writer of tragedies and is able to receive better attention from audiences.

Adaptations

[edit]Among the actors who have played Gringoire over the years in each adaptation of the novel are:

| Actor | Version |

|---|---|

| Louis Dean | 1917 film |

| Raymond Hatton | 1923 film |

| Edmond O'Brien | 1939 film |

| Robert Hirsch | 1956 film |

| Gary Raymond (voice) | 1966 BBC Television Serial |

| Christopher Gable | 1977 TV film |

| Gerry Sundquist | 1982 TV film |

| Edward Atterton | 1997 TV film |

| Bruno Pelletier | 1997–2002 musical |

| Patrick Braoudé (as Pierre-Grégoire) | Quasimodo d'El Paris (1999 parody film) |

| Richard Charest | Notre Dame de Paris, 2014-present (recurring) |

| John Eyzen | Notre Dame de Paris, 2014-present (recurring) |

| Gian Marco Schiaretti | Notre Dame de Paris, 2022 Lincoln Center |

Other

[edit]Gringoire is also the main character in the short drama Gringoire (1866) by Théodore de Banville.

The short story "La chèvre de M. Seguin" appearing in Lettres de mon moulin (1869) by Alphonse Daudet takes the form of a letter addressed to Gringoire. The story within the letter is written as an object lesson intended to convince Gringoire to accept the post of journalist for a Parisian newspaper.

References

[edit]- ^ Zarifopol-Johnston, Ilinca (1995). To Kill a Text: The Dialogic Fiction of Hugo, Dickens, and Zola. U of Delaware P. pp. 233 n.57. ISBN 978-0-87413-539-8. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ Chassang, A. (1858). "Pierre Gringoire ou un poete dramatique au temps de Louis XII et de Francois Ier". Jahrbuch für Romanische und Englische Literatur. 3: 297–. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21.