Attributes of God in Christianity

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Attributes of God in Christianity |

|---|

|

| Core attributes |

| Overarching attributes |

| Miscellaneous |

| Emotions expressed by God |

The attributes of God are specific characteristics of God discussed in Christian theology.

Classification

[edit]Many Reformed theologians distinguish between the communicable attributes (those that human beings can also have) and the incommunicable attributes (those that belong to God alone).[1] Donald Macleod, however, argues that "All the suggested classifications are artificial and misleading, not least that which has been most favoured by Reformed theologians – the division into communicable and incommunicable attributes."[2]

Many of these attributes only say what God is not – for example, saying he is immutable is saying that he does not change.

The attributes of God may be classified under two main categories:

- His infinite powers.

- His personality attributes, like holiness and love.

Millard Erickson calls these categories God's greatness and goodness respectively.[3]

Sinclair Ferguson distinguishes "essential" divine attributes, which "have been expressed and experienced in its most intense and dynamic form among the three persons of the Trinity—when nothing else existed." In this way, the wrath of God is not an essential attribute because it had "no place in the inner communion among the three persons of the eternal Trinity." Ferguson notes that it is, however, a manifestation of God's eternal righteousness, which is an essential attribute.[4]

According to Aquinas

[edit]In Aquinas' thought, Battista Mondin distinguishes between entitative attributes and personal attributes of the subsistent being that is God.[5]

Entitative attributes concerns God as regards to the fact that in Him essence and existence coincide. They are: infinity, simplicity, indivisibility, uniqueness, immutability, eternity, and spirituality (meaning absence of matter).[5]

Personal attributes of God are life (fullness, beatitude, perfection), thought, will and freedom, love and friendship. The object of the thinking and will of God is God Himself, so to speak, His essence, since He is the Highest Good and the perfection of all perfections. But God also addresses His thought and His will towards to the human creatures for their own good.[5]

Enumeration

[edit]The Westminster Shorter Catechism's definition of God is an enumeration of his attributes: "God is a Spirit, infinite, eternal, and unchangeable in his being, wisdom, power, holiness, justice, goodness, and truth."[6] This answer has been criticised, however, as having "nothing specifically Christian about it."[7] The Westminster Larger Catechism adds certain attributes to this description, such as "all-sufficient," "incomprehensible," "every where present" and "knowing all things".[8]

Aseity

[edit]The aseity of God means "God is so independent that he does not need us."[9] It is based on Acts 17:25, where it says that God "is not served by human hands, as if he needed anything" (NIV). This is often related to God's self-existence and his self-sufficiency.[10]

Eternity

[edit]The eternity of God concerns his existence beyond time. Drawing on verses such as Psalm 90:2 ("Before the mountains were born or you brought forth the whole world, from everlasting to everlasting you are God"), Wayne Grudem states that, "God has no beginning, end, or succession of moments in his own being, and he sees all time equally vividly, yet God sees events in time and acts in time."[11] The expression "Alpha and Omega" also used as a title of God in the Book of Revelation. God's eternity may be seen as an aspect of his infinity, discussed below.

Goodness

[edit]The goodness of God means that "God is the final standard of good, and all that God is and does is worthy of approval."[12] Many theologians consider the goodness of God as an overarching attribute - Louis Berkhof, for example, sees it as including kindness, love, grace, mercy and longsuffering.[13] The idea that God is "all good" is called his omnibenevolence.

Critics of Christian conceptions of God as all-good, all-knowing, and all-powerful cite the presence of evil in the world as evidence that it is impossible for all three attributes to be true; this apparent contradiction is known as the problem of evil. The evil God challenge is a thought experiment that explores whether the hypothesis that God might be evil has symmetrical consequences to a good God, and whether it is more likely that God is good, evil, or non-existent.

Graciousness

[edit]The graciousness of God is a key tenet of Christianity. In Exodus 34:5–6, it is part of the Name of God, "Yahweh, Yahweh, the compassionate and gracious God". The descriptive of God in this text is, in Jewish tradition, called the "Thirteen Attributes of Mercy".[14]

Holiness

[edit]The holiness of God is that he is separate from sin and incorruptible. Noting the refrain of "Holy, holy, holy" in Isaiah 6:3 and Revelation 4:8, R. C. Sproul points out that "only once in sacred Scripture is an attribute of God elevated to the third degree... The Bible never says that God is love, love, love; or mercy, mercy, mercy; or wrath, wrath, wrath; or justice, justice, justice. It does say that He is holy, holy, holy, that the whole earth is full of His glory."[15]

Immanence

[edit]The immanence of God refers to him being in the world. It is thus contrasted with his transcendence, but Christian theologians usually emphasise that the two attributes are not contradictory. To hold to transcendence but not immanence is deism, while to hold to immanence but not transcendence is pantheism. According to Wayne Grudem, "the God of the Bible is no abstract deity removed from, and uninterested in his creation".[16] Grudem goes on to say that the whole Bible "is the story of God's involvement with his creation", but highlights verses such as Acts 17:28, "in him we live and move and have our being".[16]

Immutability

[edit]Immutability means God cannot change. James 1:17 refers to the "Father of the heavenly lights, who does not change like shifting shadows" (NIV).[17] Herman Bavinck notes that although the Bible talks about God changing a course of action, or becoming angry, these are the result of changes in the heart of God's people (Numbers 14.) "Scripture testifies that in all these various relations and experiences, God remains ever the same."[18] Millard Erickson calls this attribute God's constancy.[3]

The immutability of God is being increasingly criticized by advocates of open theism,[19] which argues that God is open to influence through the prayers, decisions, and actions of people. Prominent adherents of open theism include Clark Pinnock, Thomas Jay Oord, John E. Sanders and Gregory Boyd.

Impassibility

[edit]The doctrine of the impassibility of God is a controversial one.[20] It is usually defined as the inability of God to suffer, while recognising that Jesus, who is believed to be God, suffered in his human nature. The Westminster Confession of Faith says that God is "without body, parts, or passions". Although most Christians historically (saint Athanasius, Augustine, Aquinas, and Calvin being examples) take this to mean that God is "without emotions whether of sorrow, pain or grief", some people interpret this as meaning that God is free from all attitudes "which reflect instability or lack of control."[21] Robert Reymond says that "it should be understood to mean that God has no bodily passions such as hunger or the human drive for sexual fulfillment."[22]

D. A. Carson argues that "although Aristotle may exercise more than a little scarcely recognized influence upon those who uphold impassibility, at its best impassibility is trying to avoid a picture of God who is changeable, given over to mood swings, dependent on his creatures."[23] In this way, impassibility is connected to the immutability of God, which says that God does not change, and to the aseity of God, which says that God does not need anything. Carson affirms that God is able to suffer, but argues that if he does so "it is because he chooses to suffer".[24]

Impeccability

[edit]The impeccability of God is closely related to his holiness. It means that God is unable to sin, which is a stronger statement than merely saying that God does not sin.[25] Robert Morey argues that God does not have the "absolute freedom" found in Greek philosophy. Whereas "the Greeks assumed the gods were 'free' to become demons if they so chose", the God of the Bible "is 'free' to act only in conformity to His nature."[26]

Incomprehensibility

[edit]The incomprehensibility of God means that he is not able to be fully known. Isaiah 40:28 says "his understanding no one can fathom".[27] Louis Berkhof states that "the consensus of opinion" through most of church history has been that God is the "Incomprehensible One". Berkhof, however, argues that, "in so far as God reveals Himself in His attributes, we also have some knowledge of His Divine Being, though even so our knowledge is subject to human limitations."[28]

Incorporeality

[edit]The incorporeality or spirituality of God refers to him being a Spirit. This is derived from Jesus' statement in John 4:24, "God is Spirit."[29] Robert Reymond suggests that it is the fact of his spiritual essence that underlies the second commandment, which prohibits every attempt to fashion an image of him."[30]

Infinity

[edit]The infinity of God includes both his eternity and his immensity. Isaiah 40:28 says that "Yahweh is the everlasting God,"[31] while Solomon acknowledges in 1 Kings 8:27 that "the heavens, even the highest heaven, cannot contain you".[32] Infinity permeates all other attributes of God: his goodness, love, power, etc. are all considered to be infinite.

The relationship between the infinity of God and mathematical infinity has often been discussed.[33] Georg Cantor's work on infinity in mathematics was accused of undermining God's infinity, but Cantor argued that God's infinity is the absolute infinite, which transcends other forms of infinity.[34]

Jealousy

[edit]J. I. Packer saw God's jealousy as "zeal to protect a love relationship or to avenge it when broken," thus making it "an aspect of his covenant love for his own people."[35]

Love

[edit]D. A. Carson speaks of the "difficult doctrine of the love of God," since "when informed Christians talk about the love of God they mean something very different from what is meant in the surrounding culture."[36] Carson distinguishes between the love the Father has for the Son, God's general love for his creation, God's "salvific stance towards his fallen world," his "particular, effectual, selecting love toward his elect," and love that is conditioned on obedience.

The love of God is particularly emphasised by adherents of the social Trinitarian school of theology. Kevin Bidwell argues that this school, which includes Jürgen Moltmann and Miroslav Volf, "deliberately advocates self-giving love and freedom at the expense of Lordship and a whole array of other divine attributes."[37]

Mission

[edit]While the mission of God is not traditionally included in this list, David Bosch has argued that "mission is not primarily an activity of the church, but an attribute of God."[38] Christopher J. H. Wright argues for a biblical basis for Mission that goes beyond the Great Commission, and suggests that "missionary texts" may sparkle like gems, but that "simply laying out such gems on a string is not yet what one could call a missiological hermeneutic of the whole Bible itself."[39]

Mystery

[edit]Many theologians see mystery as God's primary attribute because he only reveals certain knowledge to the human race. Karl Barth said "God is ultimate mystery."[40] Karl Rahner views "God" as "mystery" and theology as "the 'science' of mystery."[41] Nikolai Berdyaev deems "inexplicable Mystery" as God's "most profound definition."[42] Ian Ramsey defines God as "permanent mystery,"[43]

Omnipotence

[edit]The omnipotence of God refers to Him being "all powerful". This is often conveyed with the phrase "Almighty", as in the Old Testament title "God Almighty" (the conventional translation of the Hebrew title El Shaddai) and the title "God the Father Almighty" in the Apostles' Creed.

C. S. Lewis clarifies this concept: "His Omnipotence means power to do all that is intrinsically possible, not to do the intrinsically impossible. You may attribute miracles to him, but not nonsense. This is no limit to his power."[44]

Omnipresence

[edit]The omnipresence of God refers to him being present everywhere. Berkhof distinguishes between God's immensity and his omnipresence, saying that the former "points to the fact that God transcends all space and is not subject to its limitations," emphasising his transcendence, while the latter denotes that God "fills every part of space with His entire Being," emphasising his immanence.[45] In Psalm 139, David says, "If I go up to the heavens, you are there; if I make my bed in the depths, you are there" (Psalm 139:8, NIV).[46]

Omniscience

[edit]The omniscience of God refers to him being "all-knowing". Berkhof regards the wisdom of God as a "particular aspect of his knowledge."[47]

An argument from free will proposes that omniscience and free will are incompatible and that as a result either God does not exist or any concept of God that contains both of these elements is incorrect. An omniscient God has knowledge of the future, and thus what choices He will make. Because God's knowledge of the future is perfect, He cannot make a different choice and therefore has no free will. Alternatively, a God with free will can make different choices based on knowledge of the future, and therefore God's knowledge of the future is imperfect or limited.

Providence

[edit]While the providence of God usually refers to his activity in the world, it also implies his care for the universe, and is thus an attribute.[48] Although the word is not used in the Bible to refer to God, the concept is found in verses such as Acts 17:25, which says that God "gives all men life and breath and everything else" (NIV).[49]

A distinction is usually made between "general providence," which refers to God's continuous upholding the existence and natural order of the universe, and "special providence," which refers to God's extraordinary intervention in the life of people.[50]

Rectitude

[edit]The rectitude of God may refer to his holiness, to his justice, or to his saving activity. Martin Luther grew up believing that this referred to an attribute of God - namely, his distributive justice. Luther's change of mind and subsequent interpretation of the phrase as referring to the rectitude which God imputes to the believer was a major factor in the Protestant Reformation. More recently, however, scholars such as N. T. Wright have argued that the verse refers to an attribute of God after all - this time, his covenant faithfulness.[51]

Simplicity

[edit]The simplicity of God means he is not partly this and partly that, but that whatever he is, he is so entirely. It is thus related to the unity of God. Grudem notes that this is a less common use of the word "simple" - that is, "not composed of parts". Grudem distinguishes between God's "unity of singularity" (in that God is one God) and his "unity of simplicity".[52]

Sovereignty

[edit]The sovereignty of God is related to his omnipotence, providence, and kingship, yet it also encompasses his freedom, and is in keeping with his goodness, righteousness, holiness, and impeccability. It refers to God being in complete control as he directs all things — no person, organization, government or any other force can stop God from executing his purpose. This attribute has been particularly emphasized in Calvinism. The Calvinist writer A. W. Pink appeals to Isaiah 46:10 ("My purpose will stand, and I will do all that I please") and argues, "Subject to none, influenced by none, absolutely independent; God does as He pleases, only as He pleases always as He pleases."[53] Other Christian writers contend that the sovereign God desires to be influenced by prayer and that he "can and will change His mind when His people pray."[54][55]

Transcendence

[edit]God's transcendence means that he is outside space and time, and therefore eternal and unable to be changed by forces within the universe.[56] It is thus closely related to God's immutability, and is contrasted with his immanence.

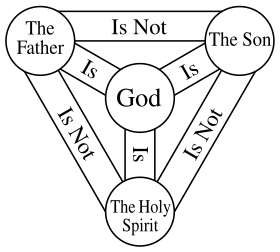

Triunity

[edit]

Triunitarian traditions of Christianity propose the Triunity of God - three persons in one (or triune): Father, Son, and the Holy Spirit.[57] Support for the doctrine of the Triunity comes from several verses on the Bible and the New Testament's trinitarian formulae, such as the Great Commission of Matthew 28:19, "Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit". Also, 1 John 5:7 (of the KJV) reads "...there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost, and these three are one", but this Comma Johanneum is almost universally rejected as a Latin corruption.[58]

The statement, known as the Shema Yisrael, after its first two words in Hebrew, says "Hear, O Israel: Yahweh our God, Yahweh is one" (Deuteronomy 6:4). In the New Testament, Jesus upholds the unity of God by quoting these words in Mark 12:29. The Apostle Paul also affirms the unity of God in verses like Ephesians 4:6.[59]

The unity of God is also related to his simplicity.

Veracity

[edit]The veracity of God means his truth-telling. Titus 1:2 refers to "God, who does not lie."[3] Among evangelicals, God's veracity is often regarded as the basis of the doctrine of biblical inerrancy. Greg Bahnsen says,

Only with an inerrant autograph can we avoid attributing error to the God of truth. An error in the original would be attributable to God Himself, because He, in the pages of Scripture, takes responsibility for the very words of the biblical authors. Errors in copies, however, are the sole responsibility of the scribes involved, in which case God's veracity is not impugned.[60]

See also

[edit]- Attributes of God in Islam

- Cataphatic theology

- Christology

- God in Christianity

- Names of God in Christianity — some of the names include attributes, traits, and characteristics

- Open theism

- Theodicy

Further reading

[edit]- Spirago, Francis (1904). . Anecdotes and Examples Illustrating The Catholic Catechism. Translated by James Baxter. Benzinger Brothers.

References

[edit]- ^ Herman Bavinck, The Doctrine of God. Edinburgh: The Banner of Truth Trust, 1979.

- ^ Donald Macleod, Behold Your God (Christian Focus Publications, 1995), 20-21.

- ^ a b c Millard Erickson, Christian Theology. Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 1985.

- ^ Ferugson, Sinclair B. (2017). "'Hallowed Be Thy Name': The Holiness of the Father". Some Pastors and Teachers: Reflecting a Biblical Vision of What Every Minister is Called to Be. Banner of Truth Trust. p. 454.

- ^ a b c Father Battista Mondin, O.P. (2022). "11-Ontologia: dall'ente all'essere sussistente". Ontologia e metafisica [Ontology and metaphysics. 11-Ontology: from the being to the subsistent being]. Filosofia (in Italian) (3rd ed.). Edizioni Studio Domenicano. pp. 200–207. ISBN 978-88-5545-053-9.

- ^ Westminster Shorter Catechism, Question and Answer 4.

- ^ James B. Jordan, "What is God?," Biblical Horizons Newsletter, No. 82.

- ^ Westminster Larger Catechism, Question and Answer 7.

- ^ D. A. Carson, The Gagging of God (Grand Rapids: Zondervan), 1996.

- ^ Frame, John M. "The Eternality and Aseity of God". The Gospel Coalition. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Wayne Grudem, Systematic Theology, 168.

- ^ Wayne Grudem, Systematic Theology, 197.

- ^ Louis Berkhof, Systematic Theology, 70-72.

- ^ Middot, Shelosh-'Esreh". Jewish Encyclopedia.

- ^ R. C. Sproul, The Holiness of God (Scripture Press Foundation, 1986), 38.

- ^ a b Wayne Grudem, Systematic Theology, 267.

- ^ Baker, Al (17 September 2010). "The Immutability of God". Banner of Truth Trust. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Herman Bavinck, The Doctrine of God, 146.

- ^ D. A. Carson, The Difficult Doctrine of the Love of God, 63.

- ^ James F. Keating and Thomas Joseph White (eds.), Divine Impassibility and the Mystery of Human Suffering. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2009.

- ^ Rowland S. Ward, The Westminster Confession for the Church Today, 27.

- ^ Robert L. Reymond, A New Systematic Theology of the Christian Faith (2nd ed., Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1998), 179.

- ^ D. A. Carson, The Difficult Doctrine of the Love of God, 55.

- ^ D. A. Carson, The Difficult Doctrine of the Love of God, 68.

- ^ Edward R. Wierenga, The Nature of God: An Inquiry Into Divine Attributes (Cornell University Press, 1989), p. 203.

- ^ Robert A. Morey, Exploring The Attributes Of God, p. 65.

- ^ Barrett, Matthew (2019). None Greater: The Undomesticated Attributes of God. Baker Books. p. 38. ISBN 9781493417575. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Louis Berkhof, Systematic Theology (London: Banner of Truth, 1949), 43.

- ^ Beeke, Joel; Smalley, Paul M. (2019). Reformed Systematic Theology, Volume 1: Revelation and God. Crossway. p. 435. ISBN 9781433559860. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Robert L. Reymond, A New Systematic Theology of the Christian Faith (2nd ed., Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1998), 167.

- ^ Peckham, John C. (2021). Divine Attributes: Knowing the Covenantal God of Scripture. Baker Books. p. 83. ISBN 9781493429417. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Ryrie, Charles C. (1999). Basic Theology: A Popular Systematic Guide to Understanding Biblical Truth. Moody Publishers. p. 47. ISBN 9781575674988. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Brendan Kneale, "God and Mathematical Infinity" Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith 50 (1998).

- ^ Yujin Nagasawa, The Existence of God (Taylor & Francis, 2011), p. 111.

- ^ J. I. Packer, Knowing God, p. 154.

- ^ Carson, Donald Arthur (2010) [2000]. The Difficult Doctrine of the Love of God (reprint, revised ed.). London: Inter-Varsity Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-84474427-5.

- ^ Kevin J. Bidwell, "Losing the Dance: is the 'divine dance' a good explanation of the Trinity?" in Iain D. Campbell and William M. Schweitzer (eds), Engaging with Keller: Thinking through the theology of an influential evangelical (Evangelical Press, 2013), p. 106.

- ^ David J. Bosch, Transforming Mission (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1991), 390.

- ^ Christopher J. H. Wright, The Mission of God: Unlocking the Bible's Grand Narrative, p. 36.

- ^ William Stacy Johnson, The Mystery of God: Karl Barth and the Postmodern Foundations of Theology (Westminster John Knox, 1997), 5.

- ^ Karl Rahner, "Reflections on Methodology in Theology" in Theological Investigations, (Darton, Longman & Todd Ltd., 1991), vol. 11, 100,102.

- ^ N. A. Berdyaev (Berdiaev), "A Consideration Concerning Theodicy" (1927 - #321), translator Fr. S. Janos, Berdyaev.com, accessed November 12, 2009.

- ^ Ian T. Ramsey, Models and Mystery, 61.

- ^ C. S. Lewis, The Problem of Pain (Fontana, 1966), 16.

- ^ Louis Berkhof, Systematic Theology (London: Banner of Truth, 1949), 61.

- ^ Jackson, Jason. "Psalm 139 — A Magnificent Portrait of God". Christian Courier. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Louis Berkhof, Systematic Theology (London: Banner of Truth, 1949), 68.

- ^ Freddoso, Alfred J. "Divine Attributes: Providence". University of Notre Dame. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ^ Creamer, Jennifer Marie (2017). God as Creator in Acts 17:24: An Historical-Exegetical Study. Wipf and Stock. p. 103. ISBN 9781532615375. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Providence in The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions.

- ^ Wright, N. T. (1997). What St Paul Really Said. Lion Books. p. 102. ISBN 9780745937977.

- ^ Wayne Grudem, Systematic Theology, 177-178.

- ^ A. W. Pink, The Sovereignty Of God Archived March 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Morris, Robert. "Why Keep Praying?". Faith Gateway. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ^ "Prayer and Its Place in God's Sovereign Plan". Focus on the Family. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ J. Gresham Machen, God Transcendent. Banner of Truth publishers, 1998. ISBN 0-85151-355-7

- ^ Alister McGrath, Understanding the Trinity, p. 120.

- ^ John Painter and Daniel J. Harrington, 1, 2, and 3 John

- ^ The IVP Women's Bible Commentary, p. 96.

- ^ Greg Bahnsen, "The Inerrancy of the Autographa".