Xenu

| Part of a series on |

| Scientology |

|---|

|

|

| Controversies |

| More |

Xenu (/ˈziːnuː/ ZEE-noo),[1][2][3] also called Xemu, is a figure in the Church of Scientology's secret "Advanced Technology",[4] a sacred and esoteric teaching.[5] According to the "Technology", Xenu was the extraterrestrial ruler of a "Galactic Confederacy" who brought billions[6][7] of his people to Earth (then known as "Teegeeack") in DC-8-like spacecraft 75 million years ago, stacked them around volcanoes, and killed them with hydrogen bombs. Official Scientology scriptures hold that the thetans (immortal spirits) of these aliens adhere to humans, causing spiritual harm.[1][8]

These events are known within Scientology as "Incident II",[4] and the traumatic memories associated with them as "The Wall of Fire" or "R6 implant". The narrative of Xenu is part of Scientologist teachings about extraterrestrial civilizations and alien interventions in earthly events, collectively described as "space opera" by L. Ron Hubbard. Hubbard detailed the story in Operating Thetan level III (OT III) in 1967, warning that the "R6 implant" (past trauma)[9] was "calculated to kill (by pneumonia, etc.) anyone who attempts to solve it".[9][10][11]

The Church of Scientology normally only reveals the Xenu story to members who have completed a lengthy sequence of courses costing large amounts of money.[12] The church avoids mention of Xenu in public statements and has gone to considerable effort to maintain the story's confidentiality, including legal action on the grounds of copyright and trade secrecy.[13] Officials of the Church of Scientology widely deny or try to hide the Xenu story.[14][15] Despite this, much material on Xenu has leaked to the public via court documents and copies of Hubbard's notes that have been distributed through the Internet.[14]

In commentary on the impact of the Xenu text, academic scholars have discussed and analyzed Hubbard's writings, their place within Scientology, and relationship to science fiction,[16] UFO religions,[17] Gnosticism,[18][19] and creation myths.[5]

Summary

The story of Xenu is covered in OT III, part of Scientology's secret "Advanced Technology" doctrines taught only to advanced members who have undergone many hours of auditing and reached the state of Clear followed by Operating Thetan levels 1 and 2.[4][12] It is described in more detail in the accompanying confidential "Assists" lecture of October 3, 1968, and is dramatized in Revolt in the Stars (a screen-story – in the form of a novel – written by L. Ron Hubbard in 1977).[4][21]

Hubbard wrote that Xenu was the ruler of a Galactic Confederacy 75 million years ago, which consisted of 26 stars and 76 planets including Earth, which was then known as "Teegeeack".[7][9][22] The planets were overpopulated, containing an average population of 178 billion.[1][6][8] The Galactic Confederacy's civilization was comparable to our own, with aliens "walking around in clothes which looked very remarkably like the clothes they wear this very minute" and using cars, trains and boats looking exactly the same as those "circa 1950, 1960" on Earth.[23]

Xenu was about to be deposed from power, so he devised a plot to eliminate the excess population from his dominions. With the assistance of psychiatrists, he gathered billions[6][7] of his citizens under the pretense of income tax inspections, then paralyzed them and froze them in a mixture of alcohol and glycol to capture their souls. The kidnapped populace was loaded into spacecraft for transport to the site of extermination, the planet of Teegeeack (Earth).[7] The appearance of these spacecraft would later be subconsciously expressed in the design of the Douglas DC-8, the only difference being that "the DC8 had fans, propellers on it and the space plane didn't".[20] When they had reached Teegeeack, the paralyzed citizens were off-loaded, and placed around the bases of volcanoes across the planet.[7][9] Hydrogen bombs were then lowered into the volcanoes and detonated simultaneously,[9] killing all but a few aliens. Hubbard described the scene in his film script, Revolt in the Stars:

Simultaneously, the planted charges erupted. Atomic blasts ballooned from the craters of Loa, Vesuvius, Shasta, Washington, Fujiyama, Etna, and many, many others. Arching higher and higher, up and outwards, towering clouds mushroomed, shot through with flashes of flame, waste and fission. Great winds raced tumultuously across the face of Earth, spreading tales of destruction ...

— L. Ron Hubbard, Revolt in the Stars[4]

The now-disembodied victims' souls, which Hubbard called thetans, were blown into the air by the blast. They were captured by Xenu's forces using an "electronic ribbon" ("which also was a type of standing wave") and sucked into "vacuum zones" around the world. The hundreds of billions[7][24] of captured thetans were taken to a type of cinema, where they were forced to watch a "three-D, super colossal motion picture" for thirty-six days. This implanted what Hubbard termed "various misleading data" (collectively termed the R6 implant) into the memories of the hapless thetans, "which has to do with God, the Devil, space opera, etcetera". This included all world religions; Hubbard specifically attributed Roman Catholicism and the image of the Crucifixion to the influence of Xenu. The two "implant stations" cited by Hubbard were said to have been located on Hawaii and Las Palmas in the Canary Islands.[25]

In addition to implanting new beliefs in the thetans, the images deprived them of their sense of personal identity. When the thetans left the projection areas, they started to cluster together in groups of a few thousand, having lost the ability to differentiate between each other. Each cluster of thetans gathered into one of the few remaining bodies that survived the explosion. These became what are known as body thetans, which are said to be still clinging to and adversely affecting everyone except Scientologists who have performed the necessary steps to remove them.[9]

A government faction known as the Loyal Officers finally overthrew Xenu and his renegades, and locked him away in "an electronic mountain trap" from which he has not escaped.[14][22][26] Although the location of Xenu is sometimes said to be the Pyrenees on Earth, this is actually the location Hubbard gave elsewhere for an ancient "Martian report station".[27][28] Teegeeack was subsequently abandoned by the Galactic Confederacy and remains a pariah "prison planet" to this day, although it has suffered repeatedly from incursions by alien "Invader Forces" since that time.[7][29][30]

In 1988, the cost of learning these secrets from the Church of Scientology was £3,830, or US$6,500.[11][31] This is in addition to the cost of the prior courses which are necessary to be eligible for OT III, which is often well over US$100,000 (roughly £77,000).[14] Belief in Xenu and body thetans is a requirement for a Scientologist to progress further along the Bridge to Total Freedom.[32] Those who do not experience the benefits of the OT III course are expected to take it and pay for it again.[26]

Scientology doctrine

Within Scientology, the Xenu story is referred to as "The Wall of Fire" or "Incident II".[4][9] Hubbard attached tremendous importance to it, saying that it constituted "the secrets of a disaster which resulted in the decay of life as we know it in this sector of the galaxy".[33] The broad outlines of the story—that 75 million years ago a great catastrophe happened in this sector of the galaxy which caused profoundly negative effects for everyone since then—are told to lower-level Scientologists; but the details are kept strictly confidential.

The OT III document asserts that Hubbard entered the Wall of Fire but emerged alive ("probably the only one ever to do so in 75,000,000 years").[25] He first publicly announced his "breakthrough" in Ron's Journal 67 (RJ67), a taped lecture recorded on September 20, 1967, to be sent to all Scientologists.[20] According to Hubbard, his research was achieved at the cost of a broken back, knee, and arm. OT III contains a warning that the R6 implant is "calculated to kill (by pneumonia etc.) anyone who attempts to solve it".[11][25] Hubbard claimed that his "tech development"—i.e. his OT materials—had neutralized this threat, creating a safe path to redemption.[9][10]

The Church of Scientology forbids individuals from reading the OT III Xenu cosmogony without first having taken prerequisite courses.[34] Scientologists warn that reading the Xenu story without proper authorization could cause pneumonia.[34][35]

In RJ67,[20] Hubbard alludes to the devastating effect of Xenu's purported genocide:

And it is very true that a great catastrophe occurred on this planet and in the other 75 planets which formed this [Galactic] Confederacy 75 million years ago. It has since that time been a desert, and it has been the lot of just a handful to try to push its technology up to a level where someone might adventure forward, penetrate the catastrophe, and undo it. We're well on our way to making this occur.

OT III also deals with Incident I, set four quadrillion[36] years ago. (Scientific consensus places the age of the universe at approximately 13.8 billion years old.[37]) In Incident I, the unsuspecting thetan was subjected to a loud snapping noise followed by a flood of luminescence, then saw a chariot followed by a trumpeting cherub. After a loud set of snaps, the thetan was overwhelmed by darkness. It is described that these traumatic memories alone separate thetans from their static (natural, godlike) state.[38]

Hubbard uses the existence of body thetans to explain many of the physical and mental ailments of humanity which, he says, prevent people from achieving their highest spiritual levels.[9] OT III tells the Scientologist to locate body thetans and release them from the effects of Incidents I and II.[9] This is accomplished in solo auditing, where the Scientologist holds both cans of an E-meter in one hand and asks questions as an auditor. The Scientologist is directed to find a cluster of body thetans, address it telepathically as a cluster, and take first the cluster, then each individual member, through Incident II, then Incident I if needed.[9] Hubbard warns that this is a painstaking procedure, and that OT levels IV to VII are necessary to continue dealing with one's body thetans.

The Church of Scientology has objected to the Xenu story being used to paint Scientology as science fiction fantasy.[39] Hubbard's statements concerning the R6 implant have been a source of contention. Critics and some Christians state that Hubbard's statements regarding R6 prove that Scientology doctrine is incompatible with Christianity,[40][41] despite the Church's statements to the contrary.[42] In "Assists", Hubbard says:[23]

Everyman is then shown to have been crucified so don't think that it's an accident that this crucifixion, they found out that this applied. Somebody somewhere on this planet, back about 600 BC, found some pieces of R6, and I don't know how they found it, either by watching madmen or something, but since that time they have used it and it became what is known as Christianity. The man on the Cross. There was no Christ. But the man on the cross is shown as Everyman.

Origins of the story

Hubbard wrote OT III in late 1966 and early 1967 in North Africa while on his way to Las Palmas to join the Enchanter, the first vessel of his private Scientology fleet (the "Sea Org").[33] (OT III says "In December 1967 I knew someone had to take the plunge", but the material was publicized well before this.) He emphasized later that OT III was his own personal discovery.

Critics of Scientology have suggested that other factors may have been at work. In a letter of the time to his wife Mary Sue,[43] Hubbard said that, in order to assist his research, he was drinking alcohol and taking stimulants and depressants ("I'm drinking lots of rum and popping pinks and greys"). His assistant at the time, Virginia Downsborough, said that she had to wean him off the diet of drugs to which he had become accustomed.[44] Russell Miller posits in Bare-faced Messiah that it was important for Hubbard to be found in a debilitated condition, so as to present OT III as "a research accomplishment of immense magnitude".[45]

Elements of the Xenu story appeared in Scientology before OT III. Hubbard's descriptions of extraterrestrial conflicts were put forward as early as 1950 in his book Have You Lived Before This Life?, and were enthusiastically endorsed by Scientologists who documented their past lives on other planets.[7]

Influence of OT III on Scientology

The 1968 and subsequent reprints of Dianetics have had covers depicting an exploding volcano, which is reportedly a reference to OT III.[4][25] In a 1968 lecture, and in instructions to his marketing staff, Hubbard explained that these images would "key in" the submerged memories of Incident II and impel people to buy the books:[23][46]

A special 'Book Mission' was sent out to promote these books, now empowered and made irresistible by the addition of these overwhelming symbols or images. Organization staff were assured that if they simply held up one of the books, revealing its cover, that any bookstore owner would immediately order crateloads of them. A customs officer, seeing any of the book covers in one's luggage, would immediately pass one on through.

— Bent Corydon, L. Ron Hubbard, Messiah or Madman?[47]

Since the 1980s, the volcano has also been depicted in television commercials advertising Dianetics. Scientology's "Sea Org", an elite group within the church that originated with Hubbard's personal staff aboard his fleet of ships, takes many of its symbols from the story of Xenu and OT III. It is explicitly intended to be a revival of the "Loyal Officers" who overthrew Xenu. Its logo, a wreath with 26 leaves, represents the 26 stars of Xenu's Galactic Confederacy.[48] According to an official Scientology dictionary, "the Sea Org symbol, adopted and used as the symbol of a Galactic Confederacy far back in the history of this sector, derives much of its power and authority from that association".[49]

In the Advanced Orgs in Edinburgh and Los Angeles, Scientology staff were at one time ordered to wear all-white uniforms with silver boots, to mimic Xenu's Galactic Patrol as depicted on the cover of Dianetics: The Evolution of a Science. This was reportedly done on the basis of Hubbard's declaration in his Flag Order 652 that mankind would accept regulation from that group which had last betrayed it—hence the imitation of Xenu's henchmen. In Los Angeles, a nightwatch was ordered to watch for returning spaceships.[50]

The Church of Scientology's own organizational structure is said to be based on that of the Galactic Confederacy. The Church's "org board" is "a refined board ... of an old galactic civilization. ... We applied Scientology to it and found out why the civilization eventually failed. They lacked a couple of departments and that was enough to mess it all up. And they only lasted 80 trillion [years]."[51]

Name

The name has been spelled both as Xenu and Xemu.[52] The Class VIII course material includes a three-page text, handwritten by Hubbard, headed "Data", in which the Xenu story is given in detail. Hubbard's indistinct handwriting makes either spelling possible,[52] particularly as the use of the name on the first page of OT III is the only known example of the name in his handwriting. In the "Assists" lecture, Hubbard speaks of "Xenu, ahhh, could be spelled X-E-M-U" and clearly says "Xemu" several times on the recording.[23] The treatment of Revolt in the Stars—which is typewritten—uses Xenu exclusively.[53]

It has been speculated that the name derives from Xemnu, an extraterrestrial comic book villain who first appeared in the story "I Was a Slave of the Living Hulk!" in Journey into Mystery #62 (November 1960). He was created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. Xemnu is a giant, hairy intergalactic criminal who escaped a prison planet, traveled to Earth, and hypnotized the entire human population. Upon Xemnu's defeat by electrician Joe Harper, Xemnu is imprisoned in a state of continual electric shock in orbit around the Sun, and humanity is left with no memory of Xemnu's existence.[54][55]

Church of Scientology's position

In its public statements, the Church of Scientology has been reluctant to allow any mention of Xenu. A passing mention by a trial judge in 1997 prompted the Church's lawyers to have the ruling sealed, although this was reversed.[56] In the relatively few instances in which it has acknowledged Xenu, Scientology has stated the story's true meaning can only be understood after years of study. They complain of critics using it to paint the religion as a science-fiction fantasy.[39]

Senior members of the Church of Scientology have several times publicly denied or minimized the importance of the Xenu story, but others have affirmed its existence. In 1995, Scientology lawyer Earl Cooley hinted at the importance of Xenu in Scientology doctrine by stating that "thousands of articles are written about Coca-Cola, and they don't print the formula for Coca-Cola".[57] Scientology has many graduated levels through which one can progress. Many who remain at lower levels in the church are unaware of much of the Xenu story which is first revealed on Operating Thetan level three, or "OT III".[25][58] Because the information imparted to members is to be kept secret from others who have not attained that level, the member must publicly deny its existence when asked. OT III recipients must sign an agreement promising never to reveal its contents before they are given the manila envelope containing the Xenu knowledge.[58][59] Its knowledge is so dangerous, members are told, that anyone learning this material before they are ready could become afflicted with pneumonia.[34]

Religious Technology Center director Warren McShane testified in a 1995 court case that the Church of Scientology receives a significant amount of its revenue from fixed donations paid by Scientologists to study the OT materials.[60] McShane said that Hubbard's work "may seem weird" to those that have not yet completed the prior levels of coursework in Scientology.[60] McShane said the story had never been secret, although maintaining there were nevertheless trade secrets contained in OT III. McShane discussed the details of the story at some length and specifically attributed the authorship of the story to Hubbard.[61][62]: 104

When John Carmichael, the president of the Church of Scientology of New York, was asked about the Xenu story, he said, as reported in the September 9, 2007, edition of The Daily Telegraph: "That's not what we believe".[63] When asked directly about the Xenu story by Ted Koppel on ABC's Nightline, Scientology leader David Miscavige said that he was taking things Hubbard said out of context.[20] However, in a 2006 interview with Rolling Stone, Mike Rinder, the then-director of the church's Office of Special Affairs, said that "It is not a story, it is an auditing level", when asked about the validity of the Xenu story.[59]

In a BBC Panorama programme that aired on May 14, 2007, senior Scientologist Tommy Davis interrupted when celebrity members were asked about Xenu, saying: "None of us know what you're talking about. It's loony. It's weird."[64] In March 2009, Davis was interviewed by investigative journalist Nathan Baca for KESQ-TV and was again asked about the OT III texts.[65] Davis told Baca "I'm familiar with the material", and called it "the confidential scriptures of the Church".[65] In an interview on ABC News Nightline, October 23, 2009,[66] Davis walked off the set when Martin Bashir asked him about Xenu. He told Bashir, "Martin, I am not going to discuss the disgusting perversions of Scientology beliefs that can be found now commonly on the internet and be put in the position of talking about things, talking about things that are so fundamentally offensive to Scientologists to discuss. ... It is in violation of my religious beliefs to talk about them." When Bashir repeated a question about Xenu, Davis pulled off his microphone and left the set.[66]

In November 2009 the Church of Scientology's representative in New Zealand, Mike Ferris, was asked in a radio interview about Xenu.[67] The radio host asked, "So what you're saying is, Xenu is a part of the religion, but something that you don't want to talk about". Ferris responded, "Sure".[67] Ferris acknowledged that Xenu "is part of the esoterica of Scientology".[68]

Leaking of the story

Despite the Church of Scientology's efforts to keep the story secret, details have been leaked over the years. OT III was first revealed in Robert Kaufman's 1972 book Inside Scientology, in which Kaufman detailed his own experiences of OT III.[69] It was later described in a 1981 Clearwater Sun article,[70] and came to greater public fame in a 1985 court case brought against Scientology by Lawrence Wollersheim. The church failed to have the documents sealed[11] and attempted to keep the case file checked out by a reader at all times, but the story was summarized in the Los Angeles Times[71] and detailed in William Poundstone's Bigger Secrets (1986) from information presented in the Wollersheim case.[72] In 1987, a book by L. Ron Hubbard Jr., L. Ron Hubbard, Messiah or Madman? quoted the first page of OT III and summarized the rest of its content.[25]

Since then, news media have mentioned Xenu in coverage of Scientology or its celebrity proponents such as Tom Cruise.[73][74][75] In 1987, the BBC's investigative news series Panorama aired a report titled "The Road to Total Freedom?" which featured an outline of the OT III story in cartoon form.[76]

On December 24, 1994, the Xenu story was published on the Internet for the first time in a posting to the Usenet newsgroup alt.religion.scientology, through an anonymous remailer.[77] This led to an online battle between Church of Scientology lawyers and detractors. Older versions of OT levels I to VII were brought as exhibits attached to a declaration by Steven Fishman on April 9, 1993, as part of Church of Scientology International v. Fishman and Geertz. The text of this declaration and its exhibits, collectively known as the Fishman Affidavit, were posted to the Internet newsgroup alt.religion.scientology in August 1995 by Arnie Lerma and on the World Wide Web by David S. Touretzky. This was a subject of great controversy and legal battles for several years. There was a copyright raid on Lerma's house (leading to massive mirroring of the documents)[78][79] and a suit against Dutch writer Karin Spaink—the Church bringing suit on copyright violation grounds for reproducing the source material, and also claiming rewordings would reveal a trade secret.

The Church of Scientology's attempts to keep Xenu secret have been cited in court findings against it. In September 2003, a Dutch court, in a ruling in the case against Karin Spaink, stated that one objective in keeping OT II and OT III secret was to wield power over members of the Church of Scientology and prevent discussion about its teachings and practices:[80]

Despite his claims that premature revelation of the OT III story was lethal, L. Ron Hubbard wrote a screenplay version under the title Revolt in the Stars in the 1970s.[17] This revealed that Xenu had been assisted by beings named Chi ("the Galactic Minister of Police") and Chu ("the Executive President of the Galactic Interplanetary Bank").[81] It has not been officially published, although the treatment was circulated around Hollywood in the early 1980s.[82] Unofficial copies of the screenplay circulate on the Internet.[83][84][85]

On March 10, 2001, a user posted the text of OT3 to the online community Slashdot. The site owners took down the comment after the Church of Scientology issued a legal notice under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act.[86][87] Critics of the Church of Scientology have used public protests to spread the Xenu secret.[88] This has included creating web sites with "xenu" in the domain name,[89][90] and displaying the name Xenu on banners[91] and protest signs.[88]

In popular culture

Versions of the Xenu story have appeared in both television shows and stage productions. The Off-Broadway satirical musical A Very Merry Unauthorized Children's Scientology Pageant, first staged in 2003 and winner of an Obie Award in 2004, featured children in alien costumes telling the story of Xenu.[92]

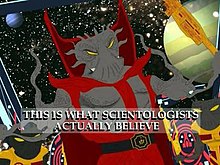

The Xenu story was also satirized in a November 2005 episode of the animated television series South Park titled "Trapped in the Closet". The Emmy-nominated episode, which also lampooned Scientologists Tom Cruise and John Travolta as closeted homosexuals, depicted Xenu as a vaguely humanoid alien with tentacles for arms, in a sequence that had the words "This Is What Scientologists Actually Believe" superimposed on screen.[93] The episode became the subject of controversy when the musician Isaac Hayes, the voice of the character "Chef" and a Scientologist, quit the show in March 2006, just prior to the episode's first scheduled re-screening, citing South Park's "inappropriate ridicule" of his religion.[94] Hayes' statement did not mention the episode in particular, but expressed his view that the show's habit of parodying religion was part of a "growing insensitivity toward personal spiritual beliefs" in the media that was also reflected in the Muhammad cartoons controversy: "There is a place in this world for satire, but there is a time when satire ends and intolerance and bigotry towards religious beliefs of others begins."[95][96] Responding to Hayes' statement, South Park co-creator Matt Stone said his resignation had "nothing to do with intolerance and bigotry and everything to do with the fact that Isaac Hayes is a Scientologist and that we recently featured Scientology in an episode of South Park ... In 10 years and over 150 episodes of South Park, Isaac never had a problem with the show making fun of Christians, Muslims, Mormons and Jews. He got a sudden case of religious sensitivity when it was his religion featured on the show. Of course we will release Isaac from his contract and we wish him well."[97] Comedy Central cancelled the repeat at short notice, choosing instead to screen two episodes featuring Hayes. A spokesman said that "in light of the events of earlier this week, we wanted to give Chef an appropriate tribute by airing two episodes he is most known for."[94] It did eventually rebroadcast the episode on July 19, 2006.[93][98] Stone and South Park co-creator Trey Parker felt that Comedy Central's owners Viacom had cancelled the repeat because of the upcoming release of the Tom Cruise film Mission: Impossible III by Paramount, another Viacom company: "I only know what we were told, that people involved with MI3 wanted the episode off the air and that is why Comedy Central had to do it. I don't know why else it would have been pulled."[99]

Commentary

Writing in the book Scientology published by Oxford University Press, contributor Mikael Rothstein observes that, "To my knowledge no real analysis of Scientology's Xenu myth has appeared in scholarly publications. The most sober and enlightening text about the Xenu myth is probably the article on Wikipedia (English version) and, even if brief, Andreas Grünschloss's piece on Scientology in Lewis (2000: 266–268)."[5] Rothstein places the Xenu text by L. Ron Hubbard within the context of a creation myth within the Scientology methodology, and characterizes it as "one of Scientology's more important religious narratives, the text that apparently constitutes the basic (sometimes implicit) mythology of the movement, the Xenu myth, which is basically a story of the origin of man on Earth and the human condition."[5] Rothstein describes the phenomenon within a belief system inspired by science fiction, and notes that the "myth about Xenu, ... in the shape of a science fiction-inspired anthropogony, explains the basic Scientological claims about the human condition."[5]

Andreas Grünschloß analyzes the Xenu text in The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements, within the context of a discussion on UFO religions.[17] He characterizes the text as "Scientology's secret mythology (contained especially in the OT III teachings)".[17] Grünschloß points out that L. Ron Hubbard, "also wrote a science fiction story called Revolt in the Stars, where he displays this otherwise arcane story about the ancient ruler Xenu in the form of an ordinary science fiction novel".[17] Grünschloß posits, "because of the connections between several motifs in Hubbard's novels and specific Scientology teachings, one might perceive Scientology as one of the rare instances where science fiction (or fantasy literature generally) is related to the successful formation of a new spiritual movement."[17] Comparing the fusion between the two genres of Hubbard's science fiction writing and Scientology creation myth, Grünschloß writes, "Although the science fiction novels are of a different genre than other 'techno-logical' disclosures of Hubbard, they are highly appreciated by participants, and Hubbard's literary output in this realm (including the latest movie, Battlefield Earth) is also well promoted by the organization."[17] Writing in the book UFO Religions edited by Christopher Partridge, Grünschloß observes, "the enthusiasm for ufology and science fiction was cultivated in the formative phase of Scientology. Indeed, even the highly arcane story of the intergalactic ruler Xenu ... is related by Hubbard in the style of a simple science fiction novel".[16]

Several authors have pointed out structural similarities between the Xenu story and the mythology of gnosticism. James A. Herrick, writing about the Xenu text in The Making of the New Spirituality: The Eclipse of the Western Religious Tradition, notes that "Hubbard's gnostic leanings are evident in his account of human origins ... In Hubbard, ideas first expressed in science fiction are seamlessly transformed into a worldwide religion with affinities to gnosticism."[18] Mary Farrell Bednarowski, writing in America's Alternative Religions, similarly states that the outline of the Xenu mythology is "not totally unfamiliar to the historian acquainted with ancient gnosticism", noting that many other religious traditions have the practice of reserving certain texts to high-level initiates.[19] Nevertheless, she writes, the Xenu story arouses suspicion in the public about Scientology and adds fuel to "the claims that Hubbard's system is the product of his creativity as a science fiction writer rather than a theologian."[19]

Authors Michael McDowell and Nathan Robert Brown discuss misconceptions about the Xenu text in their book World Religions at Your Fingertips, and observe, "Probably the most controversial, misunderstood, and frequently misrepresented part of the Scientology religion has to do with a Scientology myth commonly referred to as the Legend of Xenu. While this story has now been undoubtedly proven a part of the religion (despite the fact that church representatives often deny its existence), the story's true role in Scientology is often misrepresented by its critics as proof that they 'believe in alien parasites.' While the story may indeed seem odd, this is simply not the case."[100] The authors write that "The story is actually meant to be a working myth, illustrating the Scientology belief that humans were at one time spiritual beings, existing on infinite levels of intergalactic and interdimensional realities. At some point, the beings that we once were became trapped in physical reality (where we remain to this day). This is supposed to be the underlying message of the Xenu story, not that humans are "possessed by aliens".[100] McDowell and Brown conclude that these inappropriate misconceptions about the Xenu text have had a negative impact, "Such harsh statements are the reason many Scientologists now become passionately offended at even the mention of Xenu by nonmembers."[100]

The free speech lawyer Mike Godwin analyzes actions by the Scientology organization to protect and keep secret the Xenu text, within a discussion in his book Cyber Rights about the application of trade secret law on the Internet.[101] Godwin explains, "trade secret law protects the information itself, not merely its particular expression. Trade secret law, unlike copyright, can protect ideas and facts directly."[101] He puts forth the question, "But did the material really qualify as 'trade secrets'? Among the material the church has been trying to suppress is what might be called a 'genesis myth of Scientology': a story about a galactic despot named Xenu who decided 75 million years ago to kill a bunch of people by chaining them to volcanoes and dropping nuclear bombs on them."[101] Godwin asks, "Does a 'church' normally have 'competitors' in the trade secret sense? If the Catholics got hold of the full facts about Xenu, does this mean they'll get more market share?"[101] He comments on the ability of the Scientology organization to utilize such laws in order to contain its secret texts, "It seems likely, given what we know about the case now, that even a combination of copyright and trade secret law wouldn't accomplish what the church would like to accomplish: the total suppression of any dissemination of church documents or doctrines."[101] The author concludes, "But the fact that the church was unlikely to gain any complete legal victories in its cases didn't mean that they wouldn't litigate. It's indisputable that the mere threat of litigation, or the costs of actual litigation, may accomplish what the legal theories alone do not: the effective silencing of many critics of the church."[101]

See also

- Incident (Scientology)

- Science fiction

- Sinister Barrier, a 1939 novel with similar themes

Notes

- ^ a b c Lewis, James R. (2004). The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements. Oxford University Press. pp. 360, 427, 458. ISBN 0-19-514986-6.

- ^ Sappell, Joel; Robert W. Welkos (June 24, 1990). "Defining the Theology: The religion abounds in galactic tales". Los Angeles Times. p. 11A. Archived from the original on June 25, 2009. Retrieved January 21, 2009.

- ^ Hargrove, Mary (March 10, 1992). "Church battles critics – Mental treatment clashes with regulators, psychiatrists". Tulsa World. World Publishing Co. p. 1A.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Savino & Jones 2007, p. 55

- ^ a b c d e Rothstein, Mikael (2009). "'His name was Xenu. He used renegades ...': Aspects of Scientology's Founding Myth". In Lewis, James R. (ed.). Scientology (James R. Lewis book). Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 365, 367, 371. ISBN 978-0-19-533149-3.

- ^ a b c As 109, or thousands of millions in Long Scale

- ^ a b c d e f g h Partridge 2003, pp. 263–264

- ^ a b Scott, Michael Dennis (2004). Internet And Technology Law Desk Reference. Aspen Publishers. p. 109. ISBN 0-7355-4743-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Lamont 1986, pp. 49–50

- ^ a b Corydon & Hubbard 1987, p. 364

- ^ a b c d Koff, Stephen (December 23, 1988). "Xemu's cruel response to overpopulated world". St. Petersburg Times. p. 10A.

- ^ a b Sappell, Joel; Robert W. Welkos (June 24, 1990). "The Scientology Story". Los Angeles Times: A36:1. Archived from the original on May 24, 2008. Retrieved December 3, 2008.

- ^ Frankel, Alison (March 1996). "Making Law, Making Enemies". American Lawyer: 68.

- ^ a b c d Urban, Hugh B. (June 2006). "Fair Game: Secrecy, Security, and the Church of Scientology in Cold War America". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 74 (2). Oxford University Press: 356–389. doi:10.1093/jaarel/lfj084. ISSN 1477-4585. S2CID 143313978.

- ^ Jordison, Sam (2005). The Joy of Sects. Robson. p. 193. ISBN 1-86105-905-1.

- ^ a b Partridge 2003, pp. 187–188

- ^ a b c d e f g Grünschloß, Andreas (2004). "Waiting for the "Big Beam," UFO Religions and "UFOlogical" Themes in New Religious Movements". In James R. Lewis (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements. Oxford University Press US. pp. 427–8. ISBN 0-19-514986-6.

- ^ a b James A. Herrick (December 2004). The Making of the New Spirituality: The Eclipse of the Western Religious Tradition. InterVarsity Press. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-8308-3279-8. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

- ^ a b c Mary Farrell Bednarowski (1995). "The Church of Scientology: Lightning Rod for Cultural Boundary Conflicts". In Timothy Miller (ed.). America's Alternative Religions. SUNY Press. p. 389. ISBN 978-0-7914-2398-1. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e ABC News (November 18, 2006). "Scientology Leader Gave ABC First-Ever Interview – ABC Interview Transcript". Nightline. ABC. Retrieved August 2, 2008.

- ^ Operation Clambake (October 3, 1968). ""Assists" Lecture. October 3, 1968. No. 10 of the confidential Class VIII series of lecture". Hubbard Audio Collection. xenu.net. Retrieved December 1, 2008.

- ^ a b Reece 2007, pp. 182–186

- ^ a b c d L. Ron Hubbard "Class VIII Course, Lecture No. 10, Assists" October 3, 1968; taped lecture

- ^ A billion in Short Scale is a thousand million in Long Scale.

- ^ a b c d e f Corydon & Hubbard 1987, pp. 364–367

- ^ a b Penycate, John (April 30, 1987). "The 'extended sting operation' of Scientology". The Listener. 117 (3009). BBC Enterprises: 14, 16. ISSN 0024-4392. Archived from the original on September 9, 2016.

- ^ Rolph, C. H. (1973). Believe What You Like: What happened between the Scientologists and the National Association for Mental Health. London: Andre Deutsch Limited. ISBN 0-233-96375-8. Chapter 3: The Pharisees' View.

- ^ Evans, Christopher Riche (1973). Cults of Unreason. Harrap. p. 38. ISBN 0-245-51870-3. I. The Science Fiction Religion, Chapter: Lives Past, Lives Remembered.

- ^ Frederiksen, Tom Thygesen (2007). Scientology – en koncern af aliens. Dialogcentret. p. 16. ISBN 978-87-88527-30-8.

- ^ Connolly, Maeve (April 17, 2006). "Cruise and Co bring sci-fi religion to the masses Silent births, vehement opposition to psychiatry and a belief that Earth is a 'prison planet' inhabited by people kidnapped from outer space set Scientology apart from other religions, Maeve Connolly discovers". The Irish News. The Irish News, Ltd. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2008.

- ^ Ricks, Mike; Sarah Gorman (May 12, 1988). "The 'Hard Sell' Cult". The East Grinstead Courier. pp. 1–2, 5–7. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017.

- ^ Atack 1990, p. 382

- ^ a b Miller 1988, p. 266

- ^ a b c Browne, Michael (1998). "Should Germany Stop Worrying and Love the Octopus? Freedom of Religion and the Church of Scientology in Germany and the United States". Indiana International & Comparative Law Review. 9 (1). Indiana University: Trustees of Indiana University: 155–202. doi:10.18060/17460. 9 Ind. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 155.

- ^ Allen, Mike (August 20, 1995). "Internet Gospel: Scientology's Expensive Wisdom Now Comes Free". The New York Times.

- ^ Four thousand billion in Long Scale.

- ^ "Astronomers reevaluate the age of the universe". Space.com. January 8, 2021.

- ^ Wright, Lawrence (2013). Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood and the Prison of Belief. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 104. ISBN 9780307700667. OL 25424776M.

- ^ a b Doward, Jamie (May 16, 2004). "Lure of the celebrity sect: During an exclusive tour of Scientology's Celebrity Centre, Jamie Doward quizzed personnel about the church's teachings". The Observer. UK: Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved December 3, 2008.

- ^ Veenker, Jody (September 4, 2000). "Why Christians Object to Scientology: Craig Branch of the Apologetics Resource Center notes Clear differences". Christianity Today. Christianity Today International. Retrieved December 3, 2008.

- ^ Branch, Craig (1996). "Hubbard's Religion". The Watchman Expositor. 13 (2). Watchman Fellowship ministry. Retrieved December 3, 2008.

- ^ "Scientology and Other Practices". Church of Scientology of Michigan. 2007. Archived from the original on February 2, 2009. Retrieved December 3, 2008.

Scientology does not conflict with other religions or other religious practices.

- ^ Corydon & Hubbard 1987, pp. 58–59, 332–333

- ^ Atack 1990, p. 171

- ^ Miller 1988, p. 290

- ^ Davis, Matt (August 7, 2008). "Selling Scientology: A Former Scientologist Marketing Guru Turns Against the Church". Portland Mercury. Archived from the original on May 13, 2019. Retrieved October 31, 2008.

- ^ Corydon & Hubbard 1987, p. 361

- ^ Hubbard, "Ron's Talk to Pubs Org World Wide", tape of April 1968

- ^ Hubbard, L. Ron (1976). Modern Management Technology Defined: Hubbard dictionary of administration and management. Church of Scientology. p. 467. ISBN 0884040402. OL 8192738M.

- ^ Atack 1990, p. 190

- ^ Hubbard, L. Ron (April 6, 1965). Org Board and Livingness (audiotaped lecture). Saint Hill Special Briefing Course lectures. Church of Scientology. 2:50 minutes in.

- ^ a b Lamont 1986, p. 51

- ^ Hubbard, L. Ron (1977). Revolt in the Stars. United States Copyright Office; Registration number: DU0000105973.

- ^ Susan, Raine (2017). "Astounding History: L. Ron Hubbard's Scientology Space Opera". In Lewis, James R. (ed.). Handbook of Scientology. BRILL. pp. 554–555. ISBN 9789004330542. Retrieved December 11, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Abanes, Richard (July 1, 2009). Religions of the Stars: What Hollywood Believes and How It Affects You. Baker Books. ISBN 9781441204455. Retrieved December 11, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Prendergast, Alan (March 6, 1997). "Nightmare on the net: A web of intrigue surrounds the high-stakes legal brawl between FACTnet and the Church of Scientology". Denver Westword. Village Voice Media. Retrieved December 3, 2008.

- ^ Hall, Charles W. (August 31, 1995). "Court Lets Newspaper Keep Scientology Texts". Seattle Times. Archived from the original on August 20, 2011. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- ^ a b Atack 1990, p. 31

- ^ a b Reitman, Janet (February 23, 2006). "Inside Scientology: Unlocking the complex code of America's most mysterious religion". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 22, 2008. Retrieved December 3, 2008.

- ^ a b Brill, Ann; Ashley Packard (December 1997). "Silencing Scientology's critics on the Internet: a mission impossible?". Communications and the Law. 19 (4): 1–23.

- ^ O'Connor, Mike (August 28, 1998). "Re: Ron's Journal 67" (TXT). alt.religion.scientology. David Touretzky. lepton-2808981630510001@lepton.dialup.access.net. Retrieved December 3, 2008. (testimony under oath by Warren McShane of the Church of Scientology in RTC v. FactNet, Civil Action No. 95B2143, United States Courthouse, Denver, Colorado, September 11, 1995)

- ^ Urban, Hugh B. (2011). The Church of Scientology: A History of a New Religion. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691146089.

- ^ Oppenheimer, Mark (September 9, 2007). "Friends, thetans, countrymen". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Retrieved December 3, 2008.

- ^ Sweeney, John (May 14, 2007). "Scientology and Me". Panorama. BBC.

- ^ a b Baca, Nathan (March 12, 2009). "Scientology Official Addresses Works of L. Ron Hubbard". KESQ-TV. kesq.com.

- ^ a b Inside Scientology, ABC News Nightline, October 23, 2009.

- ^ a b Brittenden, Pat; Petra Bagust (November 29, 2009). "Scientology". Newstalk ZB. The Radio Network.

- ^ Scientology wants NZ to 'ease up' on it, The New Zealand Herald, February 7, 2013

- ^ Kaufman 1972, Part III

- ^ Leiby, Richard (August 30, 1981). "Sect courses resemble science fiction". Clearwater Sun. 68 (118).

- ^ Sappell, Joel; Robert W. Welkos (November 5, 1985). "Scientologists Block Access To Secret Documents: 1,500 crowd into courthouse to protect materials on fundamental beliefs". Los Angeles Times. p. 1.

- ^ Poundstone, William (1986). Bigger Secrets: More Than 125 Things They Prayed You'd Never Find Out. Houghton Mifflin. pp. 58–63. ISBN 0-395-38477-X.

- ^ Langan, Sean (September 4, 1995). "Warning: Prince Xenu could destroy the Net". The Independent. UK. Archived from the original on May 7, 2022. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- ^ Braund, Alison (July 7, 1995). "Inside the Cult". The Big Story (ITV). Carlton Television.

- ^ Adams, Stephen (May 14, 2007). "Scientology – a brief history". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Archived from the original on May 15, 2009. Retrieved December 3, 2008.

- ^ "Scientology – The Road to Total Freedom?". Panorama. April 27, 1987.

- ^ Lippard, Jim; Jacobsen, Jeff (1995). "Scientology v. the Internet". Skeptic. Vol. 3, no. 3. pp. 35–41. "Authorized copy". discord.org.

- ^ Grossman, Wendy (August 17, 1995). "Scientologists Fight On". The Guardian. UK. p. 2.

- ^ Brown, Andrew (May 2, 1996). "Let's All Beam Up To Heaven". The Independent. UK. p. 17.

The group responded with a campaign of raids and seizures around the US, claiming that these documents were copyrighted trade secrets. Each time one of the dissidents was raided, sympathisers copied the documents more widely.

- ^ The Court of Justice at The Hague (September 4, 2003). "LJN: AI5638, Gerechtshof 's-Gravenhage, 99/1040". de Rechtspraak (in Dutch). zoeken.rechtspraak.nl. p. Section 8.4. Retrieved December 1, 2008.

Uit de hiervoor onder 8.3 vermelde teksten blijkt dat Scientology c.s. met hun leer en organisatie de verwerping van democratische waarden niet schuwen. Uit die teksten volgt tevens dat met de geheimhouding van OT II en OT III mede wordt beoogd macht uit te oefenen over leden van de Scientology-organisatie en discussie over de leer en praktijken van de Scientology-organisatie te verhinderen.

- ^ Atack 1990, p. 245

- ^ Leiby, Richard (November 28, 1999). "John Travolta's Alien Notion: He Plays a Strange Creature In a New Sci-Fi Film, but That's Not the Only Curious Thing About This Project". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 3, 2008.

- ^ Lewis, James R., ed. (2004). The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements. Introduction by J. Gordon Melton. Oxford University Press. pp. 427, 541. ISBN 0-19-514986-6.

- ^ Lewis, James R., ed. (November 2003). The Encyclopedic Sourcebook of UFO Religions. Prometheus Books. p. 42. ISBN 1-57392-964-6.

- ^ Partridge, Christopher; J. Gordon Melton (May 6, 2004). New Religions: A Guide: New Religious Movements, Sects and Alternative Spiritualities. Oxford University Press. p. 374. ISBN 0-19-522042-0.

- ^ McCullagh, Declan (March 17, 2001). "Xenu Do, But Not on Slashdot". Wired. CondéNet, Inc. Retrieved December 3, 2008.

- ^ Malda, Rob (March 16, 2001). "Scientologists Force Comment Off Slashdot". Slashdot. slashdot.org. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

- ^ a b Ramadge, Andrew (February 10, 2008). "Scientology protests begin in Australia". NEWS.com.au. Herald and Weekly Times.

- ^ McCullagh, Declan (March 21, 2002). "Google Yanks Anti-Church Sites". Wired News. CondéNet, Inc. Retrieved December 1, 2008.

- ^ Dawson, Lorne L.; Douglas E. Cowan (January 1, 2004). Religion Online. Routledge (UK). pp. 172, 261–262. ISBN 0-415-97022-9.

- ^ Staff (December 22, 1998). "When buses become billboards". St. Petersburg Times. sptimes.com. Retrieved December 1, 2008.

- ^ Rooney, David (December 10, 2006). "Theatre Review: A Very Merry Unauthorized Children's Scientology Pageant". Variety. Retrieved November 22, 2008.

- ^ a b Robert Arp (2007). South Park and philosophy: you know, I learned something today. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 137–138. ISBN 978-1-4051-6160-2. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- ^ a b Carlson, Erin (March 21, 2006). "Rumble in 'South Park'". Concord Monitor. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^ Leslie Stratyner; James R. Keller (February 2009). The deep end of South Park: critical essays on television's shocking cartoon series. McFarland. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-7864-4307-9. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ "Isaac Hayes quits South Park". The Age. March 14, 2006. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

- ^ Booth, Robert; Agencies (March 14, 2006). "Isaac Hayes Leaves South Park". The Guardian. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

- ^ "South Park 'Trapped in the Closet' Episode to Air Again". tv.ign.com. July 12, 2006. Retrieved November 4, 2006.

- ^ Mark I. Pinsky (June 2007). The gospel according to the Simpsons: bigger and possibly even better! edition with a new afterword exploring South park, Family guy, and other animated TV shows. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 294. ISBN 978-0-664-23160-6. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

- ^ a b c McDowell, Michael; Nathan Robert Brown (2009). World Religions at Your Fingertips. Alpha. p. 271. ISBN 978-1-59257-846-7.

- ^ a b c d e f Godwin, Mike (2003). Cyber Rights: Defending Free Speech in the Digital Age. MIT Press. pp. 217–218. ISBN 0-262-57168-4.

References

- Atack, Jon (1990). A Piece of Blue Sky: Scientology, Dianetics, and L. Ron Hubbard Exposed. New York: Carol Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8184-0499-X. OCLC 20934706.

- Corydon, Bent; Hubbard, L. Ron Jr. (1987). L. Ron Hubbard, Messiah or Madman?. Secaucus, New Jersey: Lyle Stuart. ISBN 0-8184-0444-2. OCLC 16130709.

- Kaufman, Robert (1972). Inside Scientology: How I Joined Scientology and Became Superhuman. New York: Olympia Press. ISBN 0-7004-0110-5. OCLC 533305.

- Lamont, Stewart (1986). Religion Inc.: The Church of Scientology. London: Harrap. ISBN 0-245-54334-1. OCLC 23079677.

- Miller, Russell (1988). Bare-faced Messiah: The True Story of L. Ron Hubbard. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 1-55013-027-7. OCLC 17481843.

- Partridge, Christopher Hugh (2003). UFO Religions. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-26324-7. OCLC 51342721.

- Reece, Gregory L. (2007). UFO Religion: Inside Flying Saucer Cults and Culture. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-451-0.

- Savino, John; Jones, Marie D. (2007). Supervolcano: The Catastrophic Event That Changed the Course of Human History. New Page Books. ISBN 978-1-56414-953-4. OCLC 123539673.

External links

- "OT III Released" in online edition of What Is Scientology

- OT III Scholarship Page (David S. Touretzky; includes page scans, commentary, audio files)

- Revolt in the Stars summary (Grady Ward)

- Xenu Leaflet (Roland Rashleigh-Berry)

- The Fishman Affidavit: OT III (extracts and synopsis by Karin Spaink)

- A Scientific scrutiny of OT III (Peter Forde, June 1996) Claims about Xenu evaluated against scientific geology

- Research essay describing OT 3 as a drug induced hallucination posted to alt.religion.scientology on March 29, 1996, by Prignillius

- "The History Of Xenu, As Explained By L. Ron Hubbard In 8 Minutes" (Gawker.com) Extract from the "Assists" lecture of October 3, 1968

- Scientology and Christianity Examined (Archived May 29, 2006, at the Wayback Machine)

- Testimony under oath (pp274–275) from Robert Vaughn Young in RTC v. FactNet, Civil Action No. 95B2143, United States Courthouse, Denver, Colorado, September 11, 1995