Rachel

Rachel | |

|---|---|

| רָחֵל | |

Jacob and Rachel (1625) by Tanzio da Varallo | |

| Born | |

| Died | |

| Resting place | Rachel's Tomb, Bethlehem |

| Spouse | Jacob (cousin/brother-in-law/husband) |

| Children | |

| Father | Laban |

| Relatives | See list

|

Rachel (Hebrew: רָחֵל, romanized: Rāḥēl, lit. 'ewe')[1] was a Biblical figure, the favorite of Jacob's two wives, and the mother of Joseph and Benjamin, two of the twelve progenitors of the tribes of Israel. Rachel's father was Laban. Her older sister was Leah, Jacob's first wife. Her aunt Rebecca was Jacob's mother.[2]

Marriage to Jacob

[edit]

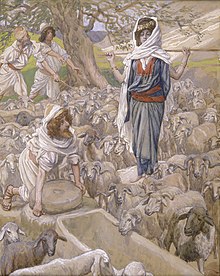

Rachel is first mentioned in the Hebrew Bible in Genesis 29 when Jacob happens upon her as she is about to water her father's flock. She was the second daughter of Laban, Rebekah's brother, making Jacob her first cousin.[2] Jacob had traveled a great distance to find Laban. Rebekah had sent him there to be safe from his angry twin brother, Esau.

During Jacob's stay, he fell in love with Rachel and agreed to work seven years for Laban in return for her hand in marriage. On the night of the wedding, the bride was veiled and Jacob did not notice that Leah, Rachel's older sister, had been substituted for Rachel. Whereas "Rachel was lovely in form and beautiful", "Leah had tender eyes".[a] Later Jacob confronted Laban, who excused his own deception by insisting that the older sister should marry first. He assured Jacob that after his wedding week was finished, he could take Rachel as a wife as well, and work another seven years as payment for her. When God "saw that Leah was unloved, he opened her womb" (Genesis 29:31),[4] and she gave birth to four sons.

Rachel, like Sarah and Rebekah, remained unable to conceive. According to biblical scholar Tikva Frymer-Kensky, "The infertility of the matriarchs has two effects: it heightens the drama of the birth of the eventual son, marking Isaac, Jacob, and Joseph as special; and it emphasizes that pregnancy is an act of God."[5]

Rachel became jealous of Leah and gave Jacob her maidservant, Bilhah, to be a surrogate mother for her. Bilhah gave birth to two sons that Rachel named and raised (Dan and Naphtali). Leah responded by offering her handmaid Zilpah to Jacob, and named and raised the two sons (Gad and Asher) that Zilpah bore. According to some commentaries, Bilhah and Zilpah were half-sisters of Leah and Rachel.[6] After Leah conceived again, Rachel finally had a son, Joseph,[2] who would become Jacob's favorite child.

Children

[edit]Rachel's son Joseph was destined to be the leader of Israel's tribes between exile and nationhood. This role is exemplified in the Biblical story of Joseph, who prepared the way in Egypt for his family's exile there.[7]

After Joseph's birth, Jacob decided to return to the land of Canaan with his family.[2] Fearing that Laban would deter him, he fled with his two wives, Leah and Rachel, and twelve children without informing his father-in-law. Laban pursued him and accused him of stealing his teraphim. Indeed, Rachel had taken her father's teraphim, hidden them inside her camel's seat cushion, and sat upon them. Laban had neglected to give his daughters their inheritance (Genesis 31:14–16).[5]

Not knowing that the teraphim were in his wife's possession, Jacob pronounced a curse on whoever had them: "With whoever you will find your gods, he will not live" (Genesis 31:32). Laban proceeded to search the tents of Jacob and his wives, but when he came to Rachel's tent, she told her father, "Let not my lord be angered that I cannot rise up before you, for the way of women is upon me" (Genesis 31:35). Laban left her alone, and the teraphim were not discovered.

Death

[edit]

Near Ephrath, Rachel went into a difficult labor with her second son, Benjamin. The midwife told her in the middle of the birth that her child was a boy.[8] Before she died, Rachel named her son Ben Oni ("son of my mourning"), but Jacob called him Ben Yamin (Benjamin). Rashi explains that Ben Yamin either means "son of the right" (i.e., "south"), since Benjamin was the only one of Jacob's sons born in Canaan, which is to the south of Paddan Aram; or it could mean "son of my days", as Benjamin was born in Jacob's old age.

Burial

[edit]Biblical scholarship distinguishes between two narratives for the site of Rachel's burial, a northern one suggesting a site north of Jerusalem near Ramah (modern Al-Ram), and a southern one placing it close to Bethlehem.

Rachel was buried on the road to Ephrath, just outside Bethlehem,[9] and not in the ancestral tomb at Machpelah (where her husband Jacob and her sister Leah were buried). Rachel's Tomb, located between Bethlehem and the Israeli settlement of Gilo, is visited by tens of thousands of visitors each year.[10]

1 Samuel 10:2 places Rachel's tomb "at Zelzah on the border of Benjamin."

Additional references in the Bible

[edit]

- Mordecai, the hero of the Book of Esther, and Queen Esther herself, were descendants of Rachel through her son Benjamin. The Book of Esther details Mordecai's lineage as "Mordecai the son of Yair, the son of Shimi, the son of Kish, a man of the right (ish yemini)" (Esther 2:5). The designation of ish yemini refers to his membership in the Tribe of Benjamin (ben yamin, son of the right). The rabbis comment that Esther's ability to remain silent in the palace of Ahasuerus, resisting the king's pressure to reveal her ancestry, was inherited from her ancestor Rachel, who remained silent even when Laban brought out Leah to marry Jacob.

- After the tribes of Ephraim and Benjamin were exiled by the Assyrians, Rachel was remembered as the classic mother who mourns and intercedes for her children.[5] Jeremiah 31:15, speaks of 'Rachel weeping for her children' (KJV). This is interpreted in Judaism as Rachel crying for an end to her descendants' sufferings and exiles following the destruction by the Babylonians of the First Temple in ancient Jerusalem. According to the Midrash, Rachel spoke before God: "If I, a mere mortal, was prepared not to humiliate my sister and was willing to take a rival into my home, how could You, the eternal, compassionate God, be jealous of idols, which have no true existence, that were brought into Your home (the Temple in Jerusalem)? Will You cause my children to be exiled on this account?" God accepted her plea and promised that, eventually, the exile would end and the Jews would return to their land.[11]

- In the second chapter of the Gospel of Matthew (part of the New Testament), this reference from Jeremiah is interpreted as a prediction of the Massacre of the Innocents by Herod the Great in his attempt to kill the young Jesus. The Jeremaic prophecy is the inspiration behind the medieval dramatic cycle Ordo Rachelis, concerned with the infancy of Jesus.

In Jewish tradition

[edit]A major theme in Jewish tradition is that of Rachel weeping for her children in Exile. This is based in part on a biblical passage (Jer. 31:14–16) "A cry is heard in Ramah—wailing, bitter weeping—Rachel weeping for her children, she refuses to be comforted for her children, who are gone." According to the rabbis, Jacob buried Rachel on the side of the road for the purpose of her future position to plead on behalf of the Jewish people.[12]

In Islam

[edit]Despite not being named in the Qur'an, Rachel (Arabic: رَحِـيْـل, Rāḥīl) is honored in Islam as the wife of Jacob and mother of Joseph,[13] who are frequently mentioned by name in the Qur'an as Yaʿqūb (Arabic: يَـعْـقُـوْب) and Yūsuf (Arabic: يُـوْسُـف), respectively.[14][15]

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Leah had tender eyes" (Biblical Hebrew: ועיני לאה רכות) (Genesis 29:17).[3] It is debated as to whether the adjective "tender" (רכות) should be taken to mean "delicate and soft" or "weary". Some translations say that it may have meant blue or light colored eyes. Some say that Leah spent most of her time weeping and praying to God to change her destined mate. Thus the Torah describes her eyes as "soft" from weeping.

References

[edit]- ^ Bible Hub

- ^ a b c d "Rachel", Jewish Virtual Library

- ^ Genesis 29:17

- ^ Genesis 29:31

- ^ a b c Frymer-Kensky, Tikva. "Rachel: Bible." Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia. 20 March 2009. Jewish Women's Archive. (Viewed on August 6, 2014)

- ^ Ginzberg, Louis (1909) The Legends of the Jews, Volume I, Chapter VI: Jacob, at sacred-texts.com

- ^ "Joseph" at jewishencyclopedia.com

- ^ Reisenberger, Azila, "Medical history: Biblical texts reveal compelling mysteries", University of Cape Town News, January 10, 2003

- ^ "Rachel" at http://jewishencyclopedia.com

- ^ "Kever Rachel Trip Breaks Barriers" by Israel National News Staff at israelnationalnews.com, Published: 11/14/05

- ^ Weisberg, Chana, "Rachel - Biblical Women" at chabad.org

- ^ "Rachel in midrash and aggadah". www.jwa.org. Accessed 2023-11-22.

- ^ "Tomb of Rahil (Rachel)". Islamic Landmarks. 24 July 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ^ Quran 12:4–102

- ^ al-Tabari, Muhammad ibn Jarir (Translated by William Brinner) (1987). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 2: Prophets and Patriarchs. SUNY. p. 150.

External links

[edit] Media related to Rachel (Biblical figure) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Rachel (Biblical figure) at Wikimedia Commons The dictionary definition of רחל at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of רחל at Wiktionary- Jewish Encyclopedia: Rachel