Makassarese language

| Makasar | |

|---|---|

| basa Mangkasaraʼ ᨅᨔ ᨆᨀᨔᨑ 𑻤𑻰𑻥𑻠𑻰𑻭 بَاسَ مَڠْكَاسَرَءْ | |

| |

| Pronunciation | [maŋˈkasaraʔ] |

| Native to | Indonesia |

| Region | South Sulawesi (Sulawesi) |

| Ethnicity | Makassarese |

Native speakers | 2.1 million (2000 census)[1] |

| Dialects |

|

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | mak |

| ISO 639-3 | mak |

| Glottolog | maka1311 |

Makassarese language

Other Makassar languages | |

Makassarese (basa Mangkasaraʼ, pronounced [basa maŋˈkasaraʔ]), sometimes called Makasar, Makassar, or Macassar, is a language of the Makassarese people, spoken in South Sulawesi province of Indonesia. It is a member of the South Sulawesi group of the Austronesian language family, and thus closely related to, among others, Buginese, also known as Bugis. The areas where Makassarese is spoken include the Gowa, Sinjai, Maros, Takalar, Jeneponto, Bantaeng, Pangkajene and Islands, Bulukumba, and Selayar Islands Regencies, and Makassar. Within the Austronesian language family, Makassarese is part of the South Sulawesi language group, although its vocabulary is considered divergent compared to its closest relatives. In 2000, Makassarese had approximately 2.1 million native speakers.

Classification

[edit]Makassarese is an Austronesian language from the South Sulawesi branch of the Malayo-Polynesian subfamily,[2] specifically the Makassaric group, which also includes both Highland and Coastal Konjo languages and the Selayar language.[3] The Konjo and Selayar language varieties are sometimes considered dialects of Makassarese. As part of the South Sulawesi language family, Makassarese is also closely related to the Bugis, Mandar, and Toraja-Saʼdan languages.[4]

In terms of vocabulary, Makassarese is considered the most distinct among the South Sulawesi languages. The average percentage of vocabulary similarity between Makassarese and other South Sulawesi languages is only 43%.[3] Specifically, the Gowa or Lakiung dialect is the most divergent; the vocabulary similarity of this dialect with other South Sulawesi languages is about 5–10 percentage points lower compared to the vocabulary similarity of Konjo and Selayar with other South Sulawesi languages.[4] However, etymostatistical analysis and functor statistics conducted by linguist Ülo Sirk shows a higher vocabulary similarity percentage (≥ 60%) between Makassarese and other South Sulawesi languages.[5] These quantitative findings support qualitative analyses that place Makassarese as part of the South Sulawesi language family.

Dialect

[edit]The language varieties within the Makassaric group form a dialect continuum. A language survey in South Sulawesi conducted by linguists and anthropologists Charles and Barbara Grimes separated the Konjo and Selayar languages from Makassarese. Meanwhile, a subsequent survey by linguists Timothy Friberg and Thomas Laskowske divided the Konjo language into three varieties: Coastal Konjo, Highland Konjo, and Bentong/Dentong.[6] However, in a book on Makassarese grammar published by the Center for Language Development and Cultivation, local linguist Abdul Kadir Manyambeang and his team include the Konjo and Selayar varieties as dialects of Makassarese.[7]

Excluding the Konjo and Selayar varieties, Makassarese can be divided into at least three dialects: the Gowa or Lakiung dialect, the Jeneponto or Turatea dialect, and the Bantaeng dialect.[8][7][9] The main differences among these varieties within the Makassar group lie in vocabulary; their grammatical structures are generally quite similar.[7][9] Speakers of the Gowa dialect tend to switch to Indonesian when communicating with speakers of the Bantaeng dialect or with speakers of the Konjo and Selayar languages, and vice versa. The Gowa dialect is generally considered the prestige variety of Makassarese. As the dialect spoken in the central region, the Gowa dialect is also commonly used by speakers of other varieties within the Makassaric group.[10]

Distribution

[edit]According to a demographic study based on the 2010 census data, about 1.87 million Indonesians over the age of five speak Makassarese as their mother tongue. Nationally, Makassarese ranks 16th among the 20 languages with the most speakers. Makassar is also the second most-spoken language in Sulawesi after Bugis, which has over 3.5 million speakers.[11][12]

The Makassarese language is primarily spoken by the Makassar people,[13] although a small percentage (1.89%) of the Bugis people also use it as their mother tongue.[14] Makassarese speakers are concentrated in the southwestern peninsula of South Sulawesi, particularly in the fertile coastal areas around Makassar, Gowa Regency, and Takalar Regency. The language is also spoken by some residents of Maros Regency and Pangkajene and Islands Regency to the north, alongside Bugis. Residents of Jeneponto and Bantaeng Regencies generally identify themselves as part of the Makassarese-speaking community, although the varieties they speak (the Jeneponto or Turatea dialect and the Bantaeng dialect) differ significantly from the dialects used in Gowa and Takalar. The closely-related Konjo language is spoken in the mountainous areas of Gowa and along the coast of Bulukumba Regency, while the Selayar language is spoken on Selayar Island, to the south of the peninsula.

Due to Makassarese contact with Aboriginal peoples in Northern Australia, a pidgin of Makassarese was used as lingua franca across the region between different Aboriginal groups, though its use declined starting in the early 20th century due to Australian restrictions against Makassarese fishermen in the region and was supplanted by English as a lingua franca.[15]

Current status

[edit]Makassarese is one of the relatively well-developed regional languages in Indonesia.[12] It is still widely used in rural areas and parts of Makassar. Makassarese is also considered important as a marker of ethnic identity. However, in urban communities, code-switching or code-mixing between Makassar and Indonesian is common. Some urban Makassar residents, especially those from the middle class or with multiethnic backgrounds, also use Indonesian as the primary language in their households.[16] Ethnologue classifies Makassar as a 6b (Threatened) language on the EGIDS scale, indicating that although the language is still commonly used in face-to-face conversations, the natural intergenerational transmission or teaching of the language is beginning to be disrupted.

Phonology

[edit]The following description of Makassarese phonology is based on Jukes (2005).[17]

Vowels

[edit]Makassarese has five vowels: /a/, /e/, /i/, /o/, /u/.[18] The mid vowels are lowered to [ɛ] and [ɔ] in absolute final position and in the vowel sequences /ea/ and /oa/.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Mid | e | o | |

| Open | a |

The vowel phoneme /e/ tends to be realized as the open-mid vowel [ɛ] when it is at the end of a word or before a syllable containing the sound [ɛ]. Compare, for instance, the pronunciation of /e/ in the word leʼbaʼ [ˈleʔ.baʔ] 'already' with mange [ˈma.ŋɛ] 'go to'.[18] The phoneme /o/ also has an open-mid allophone [ɔ] when it is at the end of a word or precedes a syllable containing the sound [ɔ], as seen in the word lompo [ˈlɔ̃m.pɔ] 'big' (compare with órasaʼ [ˈo.ra.saʔ] 'heavy').[19] Regardless of their position within a word, some speakers tend to pronounce these two vowels with a higher (closer) tongue position, making their pronunciation approach that of the phonemes /i/ and /u/.[20]

Vowels can be pronounced nasally when they are around nasal consonants within the same syllable. There are two levels of nasalization intensity for vowels: strong nasalization and weak nasalization. Weak nasalization can be found on vowels before nasal consonants that are not at the end of a word. Strong nasalization can be found on vowels before final nasal consonants or generally after nasal consonants. Nasalization can spread to vowels in syllables after nasal vowels if there are no consonants blocking it. However, the intensity of nasalization in vowels like this is not as strong as in the vowels before them, as in the pronunciation of the word niaʼ [ni͌.ãʔ] 'there is'.[21]

Consonants

[edit]There are 17 consonants in Makassarese, as outlined in the following table.

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ ⟨ny⟩[a] | ŋ ⟨ng⟩ | ||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | c | k | ʔ ⟨ʼ⟩[b] |

| voiced | b | d | ɟ ⟨j⟩ | ɡ | ||

| Fricative | s | (h)[c] | ||||

| Semivowel | j ⟨y⟩ | w | ||||

| Lateral | l | |||||

| Trill | r | |||||

| ||||||

Makassarese consonants except the glottal stop and voiced plosives can be geminated. Some instances of these might result from Proto-Malayo-Polynesian schwa phoneme *ə (now merged into a), which geminated the following consonant (*bəli > *bəlli > balli 'to buy, price' (compare Indonesian beli), contrasting with bali 'to oppose').[22]

The phoneme /t/ is the only consonant with a dental pronunciation, unlike the phonemes /n d s l r/, which are alveolar consonants. The voiceless plosive phonemes /p t k/ are generally pronounced with slight aspiration (a flow of air), as in the words katte [ˈkat̪.t̪ʰɛ] 'we', lampa [ˈlam.pʰa] 'go', and kana [ˈkʰa.nã] 'say'. The phonemes /b/ and /d/ have implosive allophones [ɓ] and [ɗ], especially in word-initial positions, such as in balu [ˈɓa.lu] 'widow', and after the sound [ʔ], as in aʼdoleng [aʔ.ˈɗo.lẽŋ] 'to let hang'. These two consonants, especially /b/ in word-initial positions, can also be realized as voiceless consonants without aspiration. The palatal phoneme /c/ can be realized as an affricate (a stop sound with a release of fricative) [cç] or even [tʃ]. The phoneme /ɟ/ can also be pronounced as an affricate [ɟʝ]. Jukes analyzes both of these consonants as stop consonants because they have palatal nasal counterparts /ɲ/, just as other oral stop consonants have their own nasal counterparts.

Phonotactics

[edit]The basic structure of syllables in Makassarese is (C1)V(C2). The position of C1 can be filled by almost any consonant, while the position of C2 has some limitations.[23] In syllables located at the end of a morpheme, C2 can be filled by a stop (T) or a nasal (N), the pronunciation of which is determined by assimilation rules. The sound T assimilates with (is pronounced the same as) voiceless consonants except [h], and is realized as [ʔ] in other contexts. The sound N is realized as a homorganic nasal (pronounced at the same articulation place) before a stop or nasal consonant, assimilates with the consonant's /l/ and /s/, and is realized as [ŋ] in other contexts. On the other hand, in syllables within root forms, Makassarese contrasts an additional sound in the C2 position besides K and N, which is /r/. This analysis is based on the fact that Makassarese distinguishes between the sequences [nr], [ʔr], and [rr] across syllables. However, [rr] can also be considered as the realization of a geminate segment rather than a sequence across syllables.[24]

| V | o | 'oh' (interjection) | ||||

| CV | ri | PREP (particle) | ||||

| VC | uʼ | 'hair' | ||||

| CVC | piʼ | 'birdlime' | ||||

| VV | io | 'yes' | ||||

| VVC | aeng | 'father' | ||||

| CVV | tau | 'person' | ||||

| CVVC | taung | 'year' | ||||

| VCVC | anaʼ | 'child' | ||||

| CVCV | sala | 'wrong' | ||||

| CVCVC | sabaʼ | 'reason' | ||||

| CVCCVC | leʼbaʼ | 'already' | ||||

| CVCVCV | binánga | 'river' | ||||

| CVCVCVC | pásaraʼ | 'market' | ||||

| CVCVCCV | kalúppa | 'forget' | ||||

| CVCCVCVC | kaʼlúrung | 'palm wood' | ||||

| CVCVCVCVC | balakeboʼ | 'herring' | ||||

| CVCVCVCCVC | kalumanynyang | 'rich' | ||||

The sounds /s l r/ can be categorized as non-nasal continuous (sounds produced without fully obstructing the flow of air through the mouth) consonants, and none of them can occupy the final position of a syllable except as part of a geminate consonant sequence.[26] Basic words that actually end with these consonants will be appended with an epenthetic vowel identical to the vowel in the preceding syllable, and closed with a glottal stop [ʔ],[27] as in the words ótereʼ /oter/ 'rope', bótoloʼ /botol/ 'bottle', and rántasaʼ /rantas/ 'mess, untidy'.[28] This additional element is also referred to as the "VC-geminate" (echo-VC) sequence, and it can affect the position of stress within a word.[29][30]

Generally, base words in Makassarese consist of two or three syllables. However, longer words can be formed due to the agglutinative nature of Makassarese and the highly productive reduplication process.[31] According to Jukes, words with six or seven syllables are commonly found in Makassarese, while base words with just one syllable (that are not borrowed from other languages) are very rare, although there are some interjections and particles consisting of only one syllable.[32]

All consonants except for /ʔ/ can appear in initial position. In final position, only /ŋ/ and /ʔ/ are found.

Consonant clusters only occur medially and (with one exception) can be analyzed as clusters of /ŋ/ or /ʔ/ + consonant. These clusters also arise through sandhi across morpheme boundaries.

| nasal/lateral | voiceless obstruents | voiced stops + r | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m | n | ɲ | ŋ | l | p | t | c | k | s | b | d | ɟ | ɡ | r | |

| /ŋ/ | mm | nn | ɲɲ | ŋŋ | ll | mp | nt | ɲc | ŋk | ns | mb | nd | ɲɟ | ŋg | nr |

| /ʔ/ | ʔm | ʔn | ʔɲ | ʔŋ | ʔl | pp | tt | cc | kk | ss | ʔb | ʔd | ʔɟ | ʔg | ʔr |

The geminate cluster /rr/ is only found in root-internal position and cannot be accounted for by the above rules.

Sequences of like vowels are contracted to a single vowel; e.g., sassa 'to wash' + -ang 'nominalizing suffix' > sassáng 'laundry', caʼdi 'small' + -i 'third person' > caʼdi 'it is small'.

Stress

[edit]The stress is generally placed on the penultimate (second-last) syllable of a base word. In reduplicated words, secondary stress will be placed on the first element, as in the word ammèkang-mékang /amˌmekaŋˈmekaŋ/ 'to fish (casually)'.[31][33] Suffixes are generally counted as part of the phonological unit receiving stress, while enclitics are not counted (extrametrical). For example, the word gássing 'strong', if the benefactive suffix -ang is added, becomes gassíngang 'stronger than' with stress on the penultimate syllable, but if given the first-person marker enclitic =aʼ, it becomes gássingaʼ 'I am strong', with stress on the antepenultimate syllable (third-last).[34]

Other morphemes counted as part of the stress-bearing unit include the affixal clitic[a], marking possession, as in the word tedóng=ku (buffalo=1.POSS) 'my buffalo'.[36] Particularly for the definite marker ≡a, this morpheme is counted as part of the stress-bearing unit only if the base word it attaches to ends in a vowel, as in the word batúa 'the stone'—compare with the stress pattern in kóngkonga 'the dog', where the base word ends in a consonant.[37][38] A word can have stress on the preantepenultimate (fourth-last) syllable if a two-syllable enclitic combination such as =mako (PFV =ma, 2 =ko) is appended; e.g., náiʼmako 'go up!'[36] The stress position can also be influenced by the process of vocalic degemination, where identical vowels across morphemes merge into one. For example, the word jappa 'walk', when the suffix -ang is added, becomes jappáng 'to walk with', with stress on the ultimate (last) syllable.[39]

The stress on base words with VC-geminate always falls on the antepenultimate syllable; for example, lápisiʼ 'layer', bótoloʼ 'bottle', pásaraʼ 'market', and Mangkásaraʼ 'Makassar', because syllables with VK-geminate are extrametrical.[29][30][28] However, the addition of suffixes -ang and -i will remove this epenthetic syllable and move the stress to the penultimate position, as in the word lapísi 'to layer'. Adding the possessive clitic suffix also shifts the stress to the penultimate position but does not remove this epenthetic syllable, as in the word botolóʼna 'its bottle'. Meanwhile, the addition of the definite marker and enclitics neither remove nor alter the stress position of this syllable, as in the words pásaraka 'that market' and appásarakaʼ 'I'm going to the market'.[26][40]

Grammar

[edit]Pronouns

[edit]Personal pronouns in the Makassar language have three forms, namely:

- free forms;

- proclitics that cross-reference S and P arguments ('absolutive');

- and enclitics that cross-reference A arguments ('ergative').

The following table shows these three forms of pronouns along with possessive markers for each series.

| Free pronouns (PRO) |

Proclitic (ERG) |

Enclitic (ABS) |

Possessive marker (POSS) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1SG | (i)nakke | ku= | =aʼ | =ku |

| 1PL.INCL/2POL | (i)katte | ki= | =kiʼ | =ta |

| 1PL.EXCL | †(i)kambe | — | *=kang | †=mang |

| 2FAM | (i)kau | nu= | =ko | =nu |

| 3 | ia | na= | =i | =na |

The first person plural inclusive pronouns are also used to refer to the second person plural and serve as a form of respect for the second person singular. The first person plural pronoun series ku= is commonly used to refer to the first person plural in modern Makassar; pronouns kambe and possessive marker =mang are considered archaic, while the enclitic =kang can only appear in combination with clitic markers of modality and aspect, such as =pakang (IPFV =pa, 1PL.EXCL =kang).[42] The plural meaning can be expressed more clearly by adding the word ngaseng 'all' after the free form, as in ia–ngaseng 'they all' and ikau–ngaseng 'you all',[43] or before the enclitic, as in ngaseng=i 'they all'. However, ngaseng cannot be paired with proclitics.

Proclitic and enclitic forms are the most common pronominal forms used to refer to the person or object being addressed (see the #Basic Clauses section for examples of their use). Free forms are less frequently used; their use is generally limited to presentative clauses (clauses that state or introduce something, see example 1), for emphasis (2), in prepositional phrases functioning as arguments or adjuncts (3), and as predicates (4).[41]

ia

3PRO

=mo

=PFV

=i

=3

(a)njo

that

allo

day

maka-

ORD-

rua

two

≡a

≡DEF

'that was the second day.'[42]

lompo-

RDP-

lompo

big

=i

=3

anaʼ

child

≡na

≡3.POSS

na

and

i-

PERS-

nakke

1PRO

tena

NEG

=pa

=IPF

ku=

1=

tianang

pregnant

'… his child is growing, and me, Iʼm not yet pregnant.'[44]

Nouns and noun phrases

[edit]Characteristics and types of nouns

[edit]Nouns in Makassarese are a class of words that can function as arguments for a predicate, allowing them to be cross-referenced by pronominal clitics.[45] Nouns can also serve as the head of a noun phrase (including relative clauses). In possessive constructions, nouns can act as either the possessor or the possessed; an affixal clitic will be attached to the possessed noun phrase. The indefiniteness of a noun can be expressed by the affixal clitic ≡a. Uninflected nouns can also function as predicates in a sentence. All of these main points are illustrated in the following example:[46]

In addition, nouns can also be specified by demonstratives, modified by adjectives, quantified by numerals, become complements in prepositional phrases, and become verbs meaning 'wear/use [the noun in question]' when affixed with the prefix aK-.[46]

Nouns that are usually affixed with the definite clitic ≡a and possessive markers are common nouns.[48] On the other hand, proper nouns such as place names, personal names, and titles (excluding kinship terms) are usually not affixed with definiteness and possessive markers but can be paired with the personal prefix i- like pronouns.[49]

Some common nouns are generic nouns that often become the core of a compound word, such as the words jeʼneʼ 'water', tai 'excrement', and anaʼ 'child'.[50] Examples of compound words derived from these generic nouns are jeʼneʼ inung 'drinking water', tai bani 'wax, beeswax' (literal meaning: 'bee excrement'), and anaʼ baine 'daughter'.[49] Kinship terms that are commonly used as greetings are also classified as common nouns, such as the words mangge 'father', anrong 'mother', and sariʼbattang 'sibling'.[51] Another example is the word daeng which is used as a polite greeting in general, or by a wife to her husband.

The other main noun group is temporal nouns, which usually appear after prepositions in adjunct constructions to express time.[50] Examples of temporal nouns are clock times (such as tetteʼ lima '5.00 [five o'clock]'), estimated times based on divisions of the day (such as bariʼbasaʼ 'morning'), days of the week, as well as dates, months, and seasons.[52]

Derived noun

[edit]Derived nouns in Makassarese are formed through several productive morphological processes, such as reduplication and affixation with pa-, ka-, and -ang, either individually or in combination.[53] The following table illustrates some common noun formation processes in Makassarese:[54][55]

| Process | Productive

meanings |

Samples | Note | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| reduplication | diminution or imitation | tau 'people' → tau-tau 'statue, doll' | [56][57] | |

| suffix pa- | pa-NOMINAL/VERBAL ROOT | actor, creator,

or user |

jarang 'horse' → pajarang 'rider';

botoroʼ 'gamble' → pabotoroʼ 'gambler' |

[58][59] |

| pa-VERB BASE[b] | instrument | akkutaʼnang 'ask' → pakkutaʼnang 'question';

anjoʼjoʼ 'point' → panjoʼjoʼ 'index finger, pointer' |

[62][63] | |

| pa-DERIVED VERBAL BASES[c] | instrument | appakagassing 'fortifiying' → pappakagassing 'tonic, fortifying medicine or drink' | [62] | |

| pa>VERB BASE<ang | place or time | aʼjeʼneʼ 'bathe' → paʼjeʼnekang 'bathing place, bathtime';

angnganre 'eat' → pangnganreang 'plate' |

[64] | |

| paK>ADJECTIVE<ang[d] | someone who is

easily ADJ, inclined to be ADJ |

garring 'sick' → paʼgarringang 'sickly person' | [65] | |

| confix ka>...<ang | ka>ADJECTIVE<ang | ADJ-ness | kodi 'bad' → kakodiang 'badness' | [66][67] |

| ka>REDUPLICATED ADJECTIVAL<ang | peak of ADJ | gassing 'strong' → kagassing-gassingang 'greatest strength'[e] | [69] | |

| ka>BASIC VERB<ang | state or process | battu 'come' → kabattuang 'arrival' | [67][70] | |

| suffix -ang | instrument | buleʼ 'carry on shoulders' → bulekang 'sedan chair' | [71][72] | |

There are some exceptions to the general patterns described above. For example, reduplication of the word oloʼ 'worm' to oloʼ-oloʼ results in a broadening of meaning to 'animal'.[73] The affixation of pa- to a verb base does not always indicate an instrument or tool, for example paʼmaiʼ 'breath, character, heart' (as in the phrase lompo paʼmaiʼ 'big-hearted') which is derived from the word aʼmaiʼ 'to breathe'.[74][75] The affixation of pa>...<ang to the verb base ammanaʼ 'to give birth' results in the word pammanakang meaning 'family', although it is possible that this word was originally a metaphor ('place to have children').[76]

Noun phrase

[edit]The components of noun phrases in the Makassarese can be categorized into three groups, namely 1) head, 2) specifier, and 3) modifier.[77]

Modifying elements always follow the head noun-they may be of various types:[78]

- modifying nouns, such as bawi romang 'wild boar' (lit. pig forest)[79]

- adjectives, such as jukuʼ lompo 'big fish'[80]

- modifying verbs, such as kappalaʼ anriʼbaʼ 'airplane' (lit. flying ship)[80]

- possesors, such as tedonna i Ali 'Ali's buffalo'[81]

- relative clauses[82]

In Makassarese, relative clauses are placed directly after the head noun without any special marker (unlike Indonesian, which requires a word like 'yang' before the relative clause). The verb within the relative clause is marked with the definite marker ≡a.[82]

tau

person

battu

come

≡a

≡DEF

ri

PREP

Japáng

Japan

'the person who came from Japan.'[82]

Verb

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2024) |

Basic clause

[edit]Intransitive clauses

[edit]In Makassarese intransitive clauses, the 'absolutive' enclitic (=ABS) is used to cross-reference the sole argument in the clause (S) if that argument is definite or salient according to the conversational context. This enclitic tends to be attached to the first constituent in a clause. The aK- prefix is commonly used to form intransitive verbs, although some verbs like tinro 'sleep' do not require this prefix.[83]

Many other types of phrases may head intransitive clauses, for example nominals (13) and pronoun (example (4) above), adjectives (14), or a prepositional phrase (15):

Transitive clauses

[edit]Verbs in transitive clauses are not affixed, but instead are marked with a pronominal proclitic indicating the A or actor and a pronominal enclitic indicating the P or undergoer.[84]

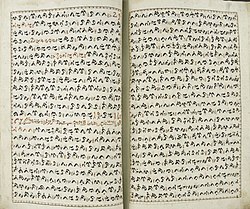

Writing systems

[edit]

Although Makassarese is now often written in Latin script, Makassarese has been traditionally written with Lontara script and Makasar script, which once was used also to write important documents in Bugis and Mandar, two related languages from Sulawesi. Further, Makassarese was written in the Serang script, a variant of the Arabic-derived Jawi script. Texts written in the Serang script are relatively rare, and mostly appear in connection with Islam-related topics. Parts of the Makassar Annals, the chronicles of the Gowa and Tallo' kingdoms, were also written using the Serang script.[22]

Latin based system

[edit]The current Latin-based forms:

| Majuscule forms (uppercase) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | Ng[i] | Ny[i] | O | P | R | S | T | U | W | Y | (ʼ)[ii] |

| Minuscule forms (lowercase) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | ng[i] | ny[i] | o | p | r | s | t | u | w | y | (ʼ)[ii] |

| IPA | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | g | h | i | ɟ | k, ʔ[iii] | l | m | n | ŋ | ɲ | o | p | r | s | t | u | w | j | ʔ |

| u | c | ɟ | ŋ | ɲ | -ʔ | (stressed vowels) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matthes (1859) | oe | t͠j | d͠j | n͠g | n͠j | ◌́, ◌̉ | ◌̂ |

| Cense (1979) | u | tj | dj | ŋ | ñ | -ʼ | ◌̀ |

| Indonesian based (1975) | u | c | j | ng | ny | -k | (not written) |

| Locally preferred | u | c | j | ng | ny | -ʼ |

Old Makassar and Lontara script

[edit]

Makassarese was historically written using Makasar script (also known as "Old Makassarese" or "Makassarese bird script" in English-language scholarly works).[85] In Makassarese the script is known as ukiriʼ jangang-jangang or huruf jangang-jangang ('bird letters'). It was used for official purposes in the kingdoms of Makasar in the 17th century but ceased to be used by the 19th century, being replaced by Lontara script.

In spite of their quite distinctive appearance, both the Makasar and Lontara scripts are derived from the ancient Brahmi script of India. Like other descendants of that script, each consonant has an inherent vowel "a", which is not marked. Other vowels can be indicated by adding diacritics above, below, or on either side of each consonant.

| ka | ga | nga | pa | ba | ma | ta | da | na | ca | ja | nya | ya | ra | la | wa | sa | a | ha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old Makassarese | 𑻠 | 𑻡 | 𑻢 | 𑻣 | 𑻤 | 𑻥 | 𑻦 | 𑻧 | 𑻨 | 𑻩 | 𑻪 | 𑻫 | 𑻬 | 𑻭 | 𑻮 | 𑻯 | 𑻰 | 𑻱 | - |

| Lontara script | ᨀ | ᨁ | ᨂ | ᨄ | ᨅ | ᨆ | ᨈ | ᨉ | ᨊ | ᨌ | ᨍ | ᨎ | ᨐ | ᨑ | ᨒ | ᨓ | ᨔ | ᨕ | ᨖ |

Ambiguity

[edit]Both scripts do not have a virama or other ways to write syllable codas in a consistent manner, even though codas occur regularly in Makassar. For example, in Makassar is baba ᨅᨅ which can correspond to six possible words: baba, babaʼ, baʼba, baʼbaʼ, bamba, and bambang.[86]

Given that Lontara script is also traditionally written without word breaks, a typical text often has many ambiguous portions which can often only be disambiguated through context. This ambiguity is analogous to the use of Arabic letters without vowel markers; readers whose native language use Arabic characters intuitively understand which vowels are appropriate in a given sentence so that vowel markers are not needed in standard everyday texts.

Even so, sometimes even context is not sufficient. In order to read a text fluently, readers may need substantial prior knowledge of the language and contents of the text in question. As an illustration, Cummings and Jukes provide the following example to illustrate how the Lontara script can produce different meanings depending on how the reader cuts and fills in the ambiguous part:

| Lontara script | Possible reading | |

|---|---|---|

| Latin | Meaning | |

| ᨕᨅᨙᨈᨕᨗ[87] | aʼbétai | he won (intransitive) |

| ambetái | he beat... (transitive) | |

| ᨊᨀᨑᨙᨕᨗᨄᨙᨄᨙᨅᨒᨉᨈᨚᨀ[88] | nakanrei pepeʼ ballaʼ datoka | fire devouring a temple |

| nakanrei pepe' Balanda tokkaʼ | fire devouring a bald Hollander | |

| ᨄᨙᨄᨙ | pepe | mute |

| pepeʼ | fire | |

| pempeng | stuck together | |

| peppeʼ | hit | |

Without knowing the actual event to which the text may be referring, it can be impossible for first time readers to determine the "correct" reading of the above examples. Even the most proficient readers may need to pause and re-interpret what they have read as new context is revealed in later portions of the same text.[86] Due to this ambiguity, some writers such as Noorduyn labelled Lontara as a defective script.[89]

Serang script

[edit]After Islam arrived in 1605, and with Malay traders using the Arabic-based Jawi script, Makassarese could also be written using Arabic letters. This was called 'serang' and was better at capturing the spoken language than the original Makassarese scripts because it could show consonants at the ends of syllables. But it wasn't widely used, with only a few surviving manuscripts. One key example is the diary of the Gowa and Tallo' courts, translated from serang into Dutch. However, Arabic script is commonly found in manuscripts to write Islamic names, dates, and religious ideas [90]

| Sound | Isolated form | Final form | Medial form | Initial form | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /c/ | چ | ـچ | ـچـ | چـ | ca |

| /ŋ/ | ڠ | ـڠ | ـڠـ | ڠـ | nga |

| /ɡ/ | ࢴ | ـࢴ | ـࢴـ | ࢴـ | gapu |

| /ɲ/ | ڽ | ـڽ | ـڽـ | ڽـ | nya |

Sample text

[edit]| Sample text | |

|---|---|

| Old Makassar script | 𑻨𑻳𑻰𑻴𑻭𑻶𑻥𑻳𑻷𑻥𑻮𑻱𑻵𑻠𑻲𑻷𑻱𑻢𑻴𑻠𑻳𑻭𑻳𑻠𑻳𑻱𑻭𑻵𑻨𑻷𑻰𑻳𑻬𑻡𑻱𑻷𑻱𑻵𑻣𑻶𑻯𑻨𑻷𑻠𑻥𑻦𑻵𑻬𑻨𑻷𑻰𑻳𑻬𑻡𑻱𑻷𑻮𑻭𑻳𑻠𑻥𑻦𑻵𑻬𑻨𑻷 𑻨𑻲𑻱𑻵𑻭𑻥𑻶𑻷𑻥𑻮𑻱𑻵𑻠𑻲𑻷𑻥𑻢𑻵𑻷𑻭𑻳𑻥𑻮𑻠𑻴𑻮𑻴𑻥𑻱𑻴𑻦𑻳𑻷 |

| Lontara script | ᨊᨗᨔᨘᨑᨚᨆᨗ᨞ᨆᨒᨕᨙᨀᨀ᨞ᨕᨂᨘᨀᨗᨑᨗᨀᨗᨕᨑᨙᨊ᨞ᨔᨗᨐᨁᨕ᨞ᨕᨙᨄᨚᨓᨊ᨞ᨀᨆᨈᨙᨐᨊ᨞ᨔᨗᨐᨁᨕ᨞ᨒᨑᨗᨀᨆᨈᨙᨐᨊ᨞ ᨊᨊᨕᨙᨑᨆᨚ᨞ᨆᨒᨕᨙᨀᨀ᨞ᨆᨂᨙ᨞ᨑᨗᨆᨒᨀᨘᨒᨘᨆᨕᨘᨈᨗ᨞ |

| Serang script | نِسُوْرُمِ مَلَائِكَكَةْ أَڠُّكِرِيْرِكِ أَرِيِنَّ سِيَࢴَاءً إِمْفُوَانَّ كَمَتِيَانَّ سِيَࢴَاءً لَنْرِ كَمَتِيَانَّ نَنَئِيْرَمَّ مَلَائِكَكَة مَاڠِيْ رِ مَلَكُ الْمَوْتِ |

| Latin Script | Nisuromi malaekaka anngukiriki arenna, siagáng empoanna kamateanna, siagáng lanri kamateanna, na naerammo malaekaka mange ri Malakulmauti. |

| Translation | The angels were ordered to record his name, the circumstances of his death, and the cause of his death, then the angels took him to Malʾak al-Mawt. |

Some common words and phrases in the Makassarese language, transcribed in the Latin script, are as follows (⟨ʼ⟩ represents the glottal stop).

| Lontara | Romanized | Indonesian | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ᨈᨕᨘ | tau | orang | people |

| ᨄᨎᨗᨀᨗ | paʼnyiki | kelelawar | bat |

| ᨕᨑᨙ | areng | nama | name |

| ᨕᨊ | anaʼ | anak | child |

| ᨔᨙᨑᨙ᨞ ᨑᨘᨓ᨞ ᨈᨒᨘ᨞ ᨕᨄ᨞ ᨒᨗᨆ᨞ | seʼre, rua, tallu, appaʼ, lima | satu, dua, tiga, empat, lima | one, two, three, four, five |

| ᨅᨕᨗᨊᨙ | baine | perempuan, istri | female, woman, wife |

| ᨅᨘᨑᨊᨙ | buraʼne | lelaki, suami | male, man, husband |

| ᨈᨅᨙ | tabeʼ | permisi, maaf | excuse me, sorry |

| ᨈᨕᨙᨊ, ᨈᨙᨊ, ᨈᨑᨙ | taena, tena, tanreʼ | tiada | none, nothing |

| ᨒᨙᨅ | leʼbaʼ | telah | already |

| ᨔᨒᨆᨀᨗ ᨅᨈᨘ ᨆᨕᨙ | salamakkiʼ battu mae | selamat datang | welcome |

| ᨕᨄ ᨕᨈᨘ ᨆᨕᨙ ᨀᨅᨑ? | apa antu mae kabaraʼ? | apa kabar? | how are you? |

| ᨅᨍᨗᨅᨍᨗᨍᨗ | bajiʼ-bajiʼji | baik-baik saja | I am fine |

| ᨊᨕᨗ ᨕᨑᨙᨊᨘ? | nai arenta? | siapa namamu? | what's your name? |

| ᨒᨀᨙᨑᨙᨀᨗ ᨆᨕᨙ? ᨒᨀᨙᨀᨗ ᨆᨕᨙ? ᨒᨀᨙᨆᨕᨗᨀᨗ? |

lakereki mae?, lakekimae?, lakemaeki? |

kamu mau ke mana? | where are you going? |

| ᨀᨙᨑᨙᨀᨗ ᨆᨕᨙ ᨕᨆᨈ | kerekiʼ mae ammantang? | kamu tinggal di mana? | where do you live? |

| ᨔᨗᨐᨄᨆᨗ ᨕᨘᨆᨘᨑᨘᨈ? | siapami umuruʼta? | berapa usiamu? | how old are you? |

| ᨔᨒᨆᨀᨗ ᨑᨗ ᨆᨂᨙᨕᨈᨙ | salamakkiʼ ri mangeanta | selamat sampai tujuan | have a safe trip |

| ᨔᨒᨆᨀᨗ ᨑᨗ ᨒᨄᨈ | salamakkiʼ ri lampanta | selamat tinggal | goodbye |

| ᨅᨈᨘ ᨑᨗ ᨀᨈᨙ | battu ri katte | tergantung padamu | it depends on you |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Affixal clitics" or "phrasal affixes" are a group of morphemes in the Makassar language that have similar properties to affixes (because they are counted to determine stress) and clitics (because they are bound to phrases rather than words). The boundary between affixal clitics and the morphemes they affix is marked with the symbol ≡. [35]

- ^ The 'verb base' referred to is a verb with the prefix aK- or aN(N)-.[60] Manyambeang, Mulya & Nasruddin (1996) analyze this form as PaK-/paN(N)- + verb root,[61] but Jukes argues that this analysis is less elegant because it assumes a greater number of affix morphemes. Furthermore, this analysis also cannot explain why PaK- and paN(N)- are commonly found on verbs that can be affixed with aK- and aN(N)-.[60]

- ^ For example, like causative verbs that are derived from verb roots with the prefix pa- (homonymous with the noun-forming prefix) or derived from adjective roots with paka-.[62]

- ^ Specifically for this form, Jukes analyzes the prefix as paK- instead of pa- + aK-, because the adjective can stand alone as a predicate without the aK- prefix.[65]

- ^ example:[68]

Kagassing-gassingannamika>

NR>

gassing-

RDP-

gassing

strong

<ang

<NR

≡na

≡3.POSS

=mo

=PFV

=i

=3

'heʼs already at the peak of his strength'

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Makasar at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Smith (2017), pp. 443–444.

- ^ a b Grimes & Grimes (1987), pp. 25–29.

- ^ a b Jukes (2005), p. 649.

- ^ Sirk (1989), pp. 72–73.

- ^ Friberg & Laskowske (1989), p. 3.

- ^ a b c Manyambeang, Mulya & Nasruddin (1996), pp. 2–4.

- ^ Grimes & Grimes (1987), pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b Jukes (2020), pp. 20–21.

- ^ Jukes (2020), p. 20.

- ^ Ananta et al. (2015), p. 278.

- ^ a b Tabain & Jukes (2016), p. 99.

- ^ Ananta et al. (2015), p. 280.

- ^ Ananta et al. (2015), p. 292.

- ^ Urry, James; Walsh, Michael (January 2011). "The lost 'Macassar language' of northern Australia" (PDF). Aboriginal History Journal. 5. doi:10.22459/AH.05.2011.06.

- ^ Jukes (2020), p. 30.

- ^ Jukes, Anthony, "Makassar" in K. Alexander Adelaar & Nikolaus Himmelmann, 2005, The Austronesian languages of Asia and Madagascar, pp. 649-682, London, Routledge ISBN 0-7007-1286-0

- ^ a b c Jukes (2020), p. 85.

- ^ Jukes (2020), p. 86.

- ^ Tabain & Jukes (2016), p. 105.

- ^ Jukes (2020), p. 90.

- ^ a b Jukes (2020), p. [page needed]

- ^ Jukes (2020), p. 93.

- ^ Jukes (2020), pp. 94–95.

- ^ a b Jukes (2020), p. 98.

- ^ a b Jukes (2020), p. 108.

- ^ Macknight (2012), p. 10.

- ^ a b Basri, Broselow & Finer (1999), p. 26.

- ^ a b Tabain & Jukes (2016), p. 107.

- ^ a b Jukes (2020), pp. 107, 109.

- ^ a b Tabain & Jukes (2016), p. 108.

- ^ Jukes (2020), pp. 97, 99–100.

- ^ Jukes (2005), p. 651–652.

- ^ Basri, Broselow & Finer (1999), pp. 25–26.

- ^ Jukes (2020), p. 133–134.

- ^ a b Jukes (2020), p. 101.

- ^ Jukes (2005), pp. 652, 656, 659.

- ^ Basri, Broselow & Finer (1999), pp. 27.

- ^ Jukes (2005), p. 652–653.

- ^ Basri, Broselow & Finer (1999), pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b Jukes (2020), p. 171.

- ^ a b Jukes (2020), p. 169.

- ^ Macknight (2012), p. 13.

- ^ a b c Jukes (2020), p. 170.

- ^ Jukes (2005), p. 657.

- ^ a b Jukes (2020), pp. 147, 196.

- ^ Jukes (2020), p. 147.

- ^ Jukes (2020), p. 196.

- ^ a b Jukes (2020), p. 199.

- ^ a b Jukes (2020), p. 197.

- ^ Jukes (2020), pp. 197, 199–200.

- ^ Jukes (2020), pp. 203–207.

- ^ Jukes (2020), p. 208.

- ^ Jukes (2020), pp. 208–222.

- ^ Manyambeang et al. (1979), pp. 38–39, 43–44, 46.

- ^ Jukes (2020), pp. 208–209.

- ^ Mursalin et al. (1981), p. 45.

- ^ Jukes (2020), p. 209–210.

- ^ Manyambeang et al. (1979), p. 38.

- ^ a b Jukes (2020), p. 211.

- ^ Manyambeang, Mulya & Nasruddin (1996), pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b c Jukes (2020), p. 211–212.

- ^ Manyambeang et al. (1979), pp. 38–39.

- ^ Jukes (2020), p. 214–215.

- ^ a b Jukes (2020), p. 216–217.

- ^ Jukes (2020), p. 216–218.

- ^ a b Manyambeang et al. (1979), p. 46.

- ^ Jukes (2020), p. 218.

- ^ Jukes (2020), p. 218–219.

- ^ Jukes (2020), p. 219–220.

- ^ Jukes (2020), p. 221–222.

- ^ Manyambeang et al. (1979), pp. 43–44.

- ^ Jukes (2020), p. 209.

- ^ Jukes (2020), p. 212–213.

- ^ Manyambeang et al. (1979), pp. 38, 57.

- ^ Jukes (2020), p. 215–216.

- ^ Jukes (2020), p. 222.

- ^ Jukes (2020), pp. 224–226.

- ^ Jukes (2020), p. 224.

- ^ a b Jukes (2020), p. 225.

- ^ Jukes (2020), pp. 137, 224.

- ^ a b c Jukes (2020), p. 226.

- ^ a b Jukes (2013a), p. 68.

- ^ a b c d e f Jukes (2013a), p. 69.

- ^ Pandey, Anshuman (2015-11-02). "L2/15-233: Proposal to encode the Makasar script in Unicode" (PDF).

- ^ a b Jukes 2014, p. 6.

- ^ Jukes 2014, p. 9.

- ^ Cummings 2002, p. [page needed].

- ^ Noorduyn 1993, p. 533.

- ^ Jukes 2006, p. 122.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ananta, Aris; Arifin, Evi Nurvidya; Hasbullah, M Sairi; Handayani, Nur Budi; Pramono, Agus (2015). Demography of Indonesia's Ethnicity. Singapura: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9789814519878.

- Basang, Djirong; Arief, Aburaerah (1981). Struktur Bahasa Makassar. Jakarta: Pusat Pembinaan dan Pengembangan Bahasa. OCLC 17565227.

- Basri, Hasan; Broselow, Ellen; Finer, Daniel (1999). "Clitics and Crisp Edges in Makassarese". Toronto Working Papers in Linguistics. 16 (2).

- Bellwood, Peter (2007). Prehistory of the Indo-Malaysian Archipelago (3 ed.). Canberra: ANU E Press. ISBN 9781921313127.

- Bulbeck, David (2008). "An Archaeological Perspective on the Diversification of the Languages of the South Sulawesi Stock". In Truman Simanjuntak (ed.). Austronesian in Sulawesi. Depok: Center for Prehistoric and Austronesian Studies. pp. 185–212. ISBN 9786028174077.

- Cummings, William (2003). "Rethinking the Imbrication of Orality and Literacy: Historical Discourse in Early Modern Makassar". Journal of Asian Studies. 62 (2): 531–551. doi:10.2307/3096248. JSTOR 3096248.

- Eberhard, David M.; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., eds. (2020). "Makasar". Ethnologue: Languages of the World (23 ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- Evans, Nicholas (1992). "Macassan Loanwords in Top End Languages". Australian Journal of Linguistics. 12 (1): 45–91. doi:10.1080/07268609208599471.

- Finer, Daniel; Basri, Hasan (2020). "Clause Truncation in South Sulawesi: Restructuring and Nominalization". In Ileana Paul (ed.). Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth Meeting of the Austronesian Formal Linguistics Association (AFLA). Ontario: University of Western Ontario. pp. 88–105.

- Friberg, Timothy; Laskowske, Thomas V. (1989). "South Sulawesi Languages" (PDF). Nusa. 31: 1–18.

- Grimes, Charles E.; Grimes, Barbara D. (1987). Languages of South Sulawesi. Pacific Linguistics. Vol. D78. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University. doi:10.15144/PL-D78.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2019). "Makasar". Glottolog 4.1. Jena, Jerman: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Jukes, Anthony (2005). "Makassar". In K. Alexander Adelaar; Nikolaus Himmelmann (eds.). The Austronesian Languages of Asia and Madagascar. London dan New York: Routledge. pp. 649–682. ISBN 9780700712861.

- ——— (2013a). "Voice, Valence, and Focus in Makassarese". Nusa. 54: 67–84. hdl:10108/71806.

- ——— (2013b). "Aspectual and Modal Clitics in Makassarese". Nusa. 55: 123–133. hdl:10108/74329.

- ——— (2015). "Nominalized Clauses in Makasar". Nusa. 59: 21–32. hdl:10108/86505.

- ——— (2020). A Grammar of Makasar. Grammars and Sketches of the World's Languages. Vol. 10. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004412668.

- Kaseng, Syahruddin (1978). Kedudukan dan Fungsi Bahasa Makassar di Sulawesi Selatan. Jakarta: Pusat Pembinaan dan Pengembangan Bahasa. OCLC 1128305657.

- Lewis, M. Paul; Simons, Gary F. (2010). "Assessing Endangerment: Expanding Fishman's GIDS" (PDF). Revue roumaine de linguistique. 55 (2): 103–120.

- Liebner, Horst (1993). "Remarks on the Terminology of Boatbuilding and Seamanship in Some Languages of South Sulawesi". Indonesia Circle. 21 (59): 18–45. doi:10.1080/03062849208729790.

- ——— (2005). "Indigenous Concepts of Orientation of South Sulawesi Sailors". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 161 (2–3): 269–317. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003710 (inactive 2024-10-23).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of October 2024 (link) - Macknight, Charles Campbell, ed. (2012). Bugis and Makasar: Two Short Grammars (PDF). South Sulawesi Studies. Vol. 1. Translated by Charles Campbell Macknight. Canberra: Karuda Press. ISBN 9780977598335.

- Manyambeang, Abdul Kadir; Syarif, Abdul Azis; Hamid, Abdul Rahim; Basang, Djirong; Arief, Aburaerah (1979). Morfologi dan Sintaksis Bahasa Makassar. Jakarta: Pusat Pembinaan dan Pengembangan Bahasa. OCLC 8186422.

- ———; Mulya, Abdul Kadir; Nasruddin (1996). Tata Bahasa Makassar. Jakarta: Pusat Pembinaan dan Pengembangan Bahasa. ISBN 9789794596821. Archived from the original on 2021-11-28. Retrieved 2020-04-11.

- Miller, Christopher (2010). "A Gujarati Origin for Scripts of Sumatra, Sulawesi and the Philippines". In Nicholas Rolle; Jeremy Steffman; John Sylak-Glassman (eds.). Proceedings of the Thirty Sixth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society. Berkeley: Berkeley Linguistics Society. pp. 276–291. doi:10.3765/bls.v36i1.3917.

- Mills, Roger Frederick (1975). "The Reconstruction of Proto-South-Sulawesi". Archipel. 10: 205–224. doi:10.3406/arch.1975.1250.

- Mursalin, Said; Basang, Djirong; Wahid, Sugira; Syarif, Abdul Azis; Rasjid, Abdul Hamid; Sannang, Ramli (1984). Sistem Perulangan Bahasa Makassar. Jakarta: Pusat Pembinaan dan Pengembangan Bahasa. OCLC 579977038.

- Noorduyn, Jacobus (1991). "The Manuscripts of the Makasarese Chronicle of Goa and Talloq: An Evaluation". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 147 (4): 454–484. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003178.

- ——— (1993). "Variation in the Bugis/Makasarese Script". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 149 (3): 533–570. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003120.

- Rabiah, Sitti (2012). Revitalisasi Bahasa Daerah Makassar Melalui Pengembangan Bahan Ajar Bahasa Makassar Sebagai Muatan Lokal. Kongres Internasional II Bahasa-Bahasa Daerah Sulawesi Selatan. Makassar: Balai Bahasa Provinsi Sulawesi Selatan dan Provinsi Sulawesi Barat. doi:10.31227/osf.io/bu64e.

- ——— (2014). Analisis Kritis Terhadap Eksistensi Bahasa Daerah Makassar Sebagai Muatan Lokal di Sekolah Dasar Kota Makassar Pasca Implementasi Kurikulum 2013. Musyawarah dan Seminar Nasional Asosiasi Jurusan/Program Studi Pendidikan Bahasa dan Sastra Indonesia (AJPBSI). Surakarta: Program Studi Pendidikan Bahasa dan Sastra Indonesia, FKIP, Universitas Sebelas Maret. doi:10.31227/osf.io/5nygu.

- Rivai, Mantasiah (2017). Sintaksis Bahasa Makassar: Tinjauan Transformasi Generatif. Yogyakarta: Deepublish. ISBN 9786024532697.

- Sirk, Ülo (1989). "On the Evidential Basis for the South Sulawesi Language Group" (PDF). Nusa. 31: 55–82.

- Smith, Alexander D. (2017). "The Western Malayo-Polynesian Problem". Oceanic Linguistics. 56 (2): 435–490. doi:10.1353/ol.2017.0021.

- Tabain, Marija; Jukes, Anthony (2016). "Makasar". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 46 (1): 99–111. doi:10.1017/S002510031500033X.

- Urry, James; Walsh, Michael (1981). "The Lost 'Macassar Language' of Northern Australia". Aboriginal History. 5 (2): 90–108. doi:10.22459/AH.05.2011.06.

- Walker, Alan; Zorc, R. David (1981). "Austronesian Loanwords in Yolngu-Matha of Northeast Arnhem Land". Aboriginal History. 5 (2): 109–134. doi:10.22459/AH.05.2011.07.

External links

[edit]