Optic nerve

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (June 2018) |

| Optic nerve | |

|---|---|

The left optic nerve and the optic tracts. | |

| Details | |

| Innervates | Vision |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | nervus opticus |

| MeSH | D009900 |

| NeuroNames | 289 |

| TA98 | A14.2.01.006 A15.2.04.024 |

| TA2 | 6183 |

| FMA | 50863 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

| Cranial nerves |

|---|

|

In neuroanatomy, the optic nerve, also known as the second cranial nerve, cranial nerve II, or simply CN II, is a paired cranial nerve that transmits visual information from the retina to the brain. In humans, the optic nerve is derived from optic stalks during the seventh week of development and is composed of retinal ganglion cell axons and glial cells; it extends from the optic disc to the optic chiasma and continues as the optic tract to the lateral geniculate nucleus, pretectal nuclei, and superior colliculus.[1][2]

Structure

[edit]The optic nerve has been classified as the second of twelve paired cranial nerves, but it is technically a myelinated tract of the central nervous system, rather than a classical nerve of the peripheral nervous system because it is derived from an out-pouching of the diencephalon (optic stalks) during embryonic development. As a consequence, the fibers of the optic nerve are covered with myelin produced by oligodendrocytes, rather than Schwann cells of the peripheral nervous system, and are encased within the meninges.[3] Peripheral neuropathies like Guillain–Barré syndrome do not affect the optic nerve. However, most typically, the optic nerve is grouped with the other eleven cranial nerves and is considered to be part of the peripheral nervous system.

The optic nerve is ensheathed in all three meningeal layers (dura, arachnoid, and pia mater) rather than the epineurium, perineurium, and endoneurium found in peripheral nerves. Fiber tracts of the mammalian central nervous system have only limited regenerative capabilities compared to the peripheral nervous system.[4] Therefore, in most mammals, optic nerve damage results in irreversible blindness. The fibers from the retina run along the optic nerve to nine primary visual nuclei in the brain, from which a major relay inputs into the primary visual cortex.

The optic nerve is composed of retinal ganglion cell axons and glia. Each human optic nerve contains between 770,000 and 1.7 million nerve fibers,[5] which are axons of the retinal ganglion cells of one retina. In the fovea, which has high acuity, these ganglion cells connect to as few as 5 photoreceptor cells; in other areas of the retina, they connect to thousands of photoreceptors.

The optic nerve leaves the orbit (eye socket) via the optic canal, running postero-medially towards the optic chiasm, where there is a partial decussation (crossing) of fibers from the temporal visual fields (the nasal hemi-retina) of both eyes. The proportion of decussating fibers varies between species, and is correlated with the degree of binocular vision enjoyed by a species.[6] Most of the axons of the optic nerve terminate in the lateral geniculate nucleus from where information is relayed to the visual cortex, while other axons terminate in the pretectal area[7] and are involved in reflexive eye movements. Other axons terminate in the suprachiasmatic nucleus and are involved in regulating the sleep-wake cycle. Its diameter increases from about 1.6 mm within the eye to 3.5 mm in the orbit to 4.5 mm within the cranial space. The optic nerve component lengths are 1 mm in the globe, 24 mm in the orbit, 9 mm in the optic canal, and 16 mm in the cranial space before joining the optic chiasm. There, partial decussation occurs, and about 53% of the fibers cross to form the optic tracts. Most of these fibers terminate in the lateral geniculate body.[1]

Based on this anatomy, the optic nerve may be divided into four parts as indicated in the image at the top of this section (this view is from above as if you were looking into the orbit after the top of the skull had been removed): 1. the optic head (which is where it begins in the eyeball (globe) with fibers from the retina); 2. orbital part (which is the part within the orbit); 3. intracanicular part (which is the part within a bony canal known as the optic canal); and, 4. cranial part (the part within the cranial cavity, which ends at the optic chiasm).[2]

From the lateral geniculate body, fibers of the optic radiation pass to the visual cortex in the occipital lobe of the brain. In more specific terms, fibers carrying information from the contralateral superior visual field traverse Meyer's loop to terminate in the lingual gyrus below the calcarine fissure in the occipital lobe, and fibers carrying information from the contralateral inferior visual field terminate more superiorly, to the cuneus.[8]

Function

[edit]The optic nerve transmits all visual information including brightness perception, color perception and contrast (visual acuity). It also conducts the visual impulses that are responsible for two important neurological reflexes: the light reflex and the accommodation reflex. The light reflex refers to the constriction of both pupils that occurs when light is shone into either eye. The accommodation reflex refers to the swelling of the lens of the eye that occurs when one looks at a near object (for example: when reading, the lens adjusts to near vision).[1]

The eye's blind spot is a result of the absence of photoreceptors in the area of the retina where the optic nerve leaves the eye.[1]

Clinical significance

[edit]Disease

[edit]Damage to the optic nerve typically causes permanent and potentially severe loss of vision, as well as an abnormal pupillary reflex, which is important for the diagnosis of nerve damage.

The type of visual field loss will depend on which portions of the optic nerve were damaged. In general, the location of the damage in relation to the optic chiasm (see diagram above) will affect the areas of vision loss. Damage to the optic nerve that is anterior, or in front of the optic chiasm (toward the face) causes loss of vision in the eye on the same side as the damage. Damage at the optic chiasm itself typically causes loss of vision laterally in both visual fields or bitemporal hemianopsia (see image to the right). Such damage may occur with large pituitary tumors, such as pituitary adenoma. Finally, damage to the optic tract, which is posterior to, or behind the chiasm, causes loss of the entire visual field from the side opposite the damage, e.g. if the left optic tract were cut, there would be a loss of vision from the entire right visual field.

Injury to the optic nerve can be the result of congenital or inheritable problems like Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy, glaucoma, trauma, toxicity, inflammation, ischemia, infection (very rarely), or compression from tumors or aneurysms. By far, the three most common injuries to the optic nerve are from glaucoma; optic neuritis, especially in those younger than 50 years of age; and anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, usually in those older than 50.

Glaucoma is a group of diseases involving loss of retinal ganglion cells causing optic neuropathy in a pattern of peripheral vision loss, initially sparing central vision. Glaucoma is frequently associated with increased intraocular pressure that damages the optic nerve as it exits the eyeball. The trabecular meshwork assists the drainage of aqueous humor fluid. The presence of excess aqueous humor, increases IOP, yielding the diagnosis and symptoms of glaucoma.[9]

Optic neuritis is inflammation of the optic nerve. It is associated with a number of diseases, the most notable one being multiple sclerosis. The patient will likely experience varying vision loss and eye pain. The condition tends to be episodic.

Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy is commonly known as a "stroke of the optic nerve" and affects the optic nerve head (where the nerve exits the eyeball). There is usually a sudden loss of blood supply and nutrients to the optic nerve head. Vision loss is typically sudden and most commonly occurs upon waking up in the morning. This condition is most common in diabetic patients 40–70 years old.

Other optic nerve problems are less common. Optic nerve hypoplasia is the underdevelopment of the optic nerve resulting in little to no vision in the affected eye. Tumors, especially those of the pituitary gland, can put pressure on the optic nerve causing various forms of visual loss. Similarly, cerebral aneurysms, a swelling of blood vessel(s), can also affect the nerve. Trauma can cause serious injury to the nerve. Direct optic nerve injury can occur from a penetrating injury to the orbit, but the nerve can also be injured by indirect trauma in which severe head impact or movement stretches or even tears the nerve.[1]

Ophthalmologists and optometrists can detect and diagnose some optic nerve diseases but neuro-ophthalmologists are often best suited to diagnose and treat diseases of the optic nerve. The International Foundation for Optic Nerve Diseases (IFOND) sponsors research and provides information on a variety of optic nerve disorders.

Additional images

[edit]-

MRI scan of human eye showing optic nerve.

-

The ophthalmic artery derived from internal carotid artery and its branches. (optic nerve is yellow)

-

Superficial dissection of brain-stem. Lateral view.

-

Dissection of brain-stem. Lateral view.

-

Scheme showing central connections of the optic nerves and optic tracts.

-

Nerves of the orbit. Seen from above.

-

Nerves of the orbit, and the ciliary ganglion. Side view.

-

The terminal portion of the optic nerve and its entrance into the eyeball, in horizontal section.

-

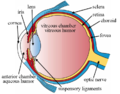

Structures of the eye labeled

-

This image shows another labeled view of the structures of the eye

-

Optic nerve. Deep dissection. Inferior view.

-

Optic nerve. Deep dissection. Inferior view.

-

Optic nerve

-

Optic nerve

-

Human brain dura mater (reflections)

-

Optic nerve

-

Optic nerve

-

Optic nerve

-

Cerebrum. Inferior view. Deep dissection.

-

Cerebral peduncle, optic chasm, cerebral aqueduct. Inferior view. Deep dissection.

See also

[edit]- Ophthalmic nerve (CN V1)

- Bistratified cell

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Vilensky, Joel; Robertson, Wendy; Suarez-Quian, Carlos (2015). The Clinical Anatomy of the Cranial Nerves: The Nerves of "On Olympus Towering Top". Ames, Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1118492017.

- ^ a b Selhorst, John; Chen, Yanjun (February 2009). "The Optic Nerve". Seminars in Neurology. 29 (1): 029–035. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1124020. ISSN 0271-8235. PMID 19214930.

- ^ Smith, Austen M.; Czyz, Craig N. (2021). "Neuroanatomy, Cranial Nerve 2 (Optic)". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29939684. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ Benowitz, Larry; Yin, Yuqin (August 2010). "Optic Nerve Regeneration". Archives of Ophthalmology. 128 (8): 1059–1064. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.152. ISSN 0003-9950. PMC 3072887. PMID 20697009.

- ^ Jonas, Jost B.; et al. (May 1992). "Human optic nerve fiber count and optic disc size". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 33 (6): 2012–8. PMID 1582806.

- ^ Textbook of Veterinary Anatomy, 4th Edition. Dyce, Sack and Wensing

- ^ Belknap, Dianne B.; McCrea, Robert A. (1988-02-01). "Anatomical connections of the prepositus and abducens nuclei in the squirrel monkey". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 268 (1): 13–28. doi:10.1002/cne.902680103. ISSN 0021-9967. PMID 3346381. S2CID 21565504.

- ^ "Vision". casemed.case.edu. Archived from the original on 2020-01-26. Retrieved 2020-01-23.

- ^ "The Eye's Drainage System, the Trabecular Meshwork & Glaucoma | BrightFocus Foundation". www.brightfocus.org. Retrieved 2022-01-10.

External links

[edit]- The optic nerve on MRI

- Stained brain slice images which include the "optic%20nerve" at the BrainMaps project

- IFOND

- online case history – Optic nerve analysis with both scanning laser polarimetry with variable corneal compensation (GDx VCC) and confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (HRT II - Heidelberg Retina Tomograph). Also includes actual fundus photos.

- Animations of extraocular cranial nerve and muscle function and damage (University of Liverpool)

- lesson3 at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (orbit4)

- cranialnerves at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (II)