Fast, Cheap & Out of Control

| Fast, Cheap & Out of Control | |

|---|---|

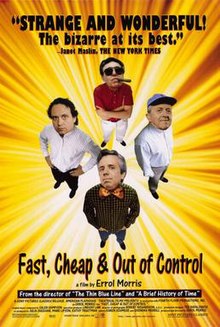

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Errol Morris |

| Produced by | Errol Morris |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Robert Richardson |

| Edited by | Shondra Merrill Karen Schmeer |

| Music by | Caleb Sampson |

| Distributed by | Sony Pictures Classics |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 82 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $878,960 (USA) |

Fast, Cheap & Out of Control is a 1997 documentary film by filmmaker Errol Morris.[1]

Summary

[edit]The film profiles four subjects with extraordinary careers: Dave Hoover, a wild-animal tamer; George Mendonça, a topiary gardener at Green Animals Topiary Garden in Portsmouth, Rhode Island; Ray Mendez, an expert on naked mole-rats who has designed an exhibit on the animals for the Philadelphia Zoo; and Rodney Brooks, an MIT scientist who works in robotics. In the interviews with the men, which act as the guiding narration for the film, they discuss their personal lives, what led them to their professions, what challenges they face in their work, and their thoughts about what they see in the future for their careers, their fields, and the world.

Style

[edit]In Fast, Cheap & Out of Control, Morris uses a camera technique he invented which allows the interview subject to maintain eye contact with the interviewer while also looking directly into the camera, seemingly making eye contact with the audience. The invention is called the Interrotron, and Morris uses it in a number of his other films. According to Morris, this invention alters interviews in the sense that "no longer is it the interviewer, the camera, and the subject; with the Interrotron, the conversation is between the camera/interviewer and the subject."[2]

Morris uses the four main subjects to narrate the film, while displaying more artistic freedom through visual mechanisms. The cinematographer, Robert Richardson, uses many of the same camera techniques he used in Oliver Stone's films JFK and Natural Born Killers. In addition to 35 mm cameras, he also uses Super 8 mm film. Some footage was even transferred to video and then filmed again being played "off a low-resolution television set."[3]

The film also uses footage from other sources, such as movie clips, documentary footage, and cartoons.[4] Hoover's idol Clyde Beatty appears via portions of a film (The Big Cage, 1933) and serial (Darkest Africa, 1936) in which he starred, and there are clips of malicious robots from the serial Zombies of the Stratosphere (1952).

After using the first moments in the film to establish the characters one by one with film clips that correspond to each subject, Morris then begins to mix footage relating to one subject with the narration of another in order to establish themes shared by the different subjects.

Morris said that "The multiple [film and video] formats make you aware of imagery as imagery, but I can't imagine this film without the narration by the characters. The ideas come from the relation between what is being said and what is being seen. If there isn't a connection, it doesn't work -- and I can testify to this from empirical knowledge gathered in an editing room.'' Morris credited his editor, Karen Schmeer, with "saving" the film. The day after she died, he wrote on Twitter: "An extraordinary editor makes possible something that would not have been possible without them. Karen Schmeer was an extraordinary editor."[5]

Background

[edit]Morris' initial intention for the film was to create a profile-based film with no clear relation between its subjects. This was in contrast to his previous films, in which the interview subjects were related by events, like in Gates of Heaven and The Thin Blue Line,[6] or place of residency, like in Vernon, Florida.[7]

The title of the film is a play on the old engineer's adage that, out of "fast", "cheap", and "reliable", you can only produce an end consumer product that is two of those three (the classic example is a car). Brooks, the robot scientist in the film, published a paper in the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society in 1989 titled "Fast, Cheap and Out of Control: A Robot Invasion of the Solar System".[8] In it, he speculated that it might be more effective to send one hundred one-kilogram robots into space instead of a single hundred-kilogram robot, replacing the need for reliability with chance and sheer numbers, as systems in nature have learned to do. The advantage would be that, if a single robot malfunctioned or got destroyed, there would still be plenty of other working robots to do the exploring.

In a profile of Morris, Roger Ebert wrote that if he had to describe the film, he'd "say it's about people who are trying to control things--to take upon themselves the mantle of God." Morris agrees that "There is a Frankenstein element. They're all involved in some very odd inquiry about life...There's something mysterious in each of the stories, something melancholy as well as funny. And there's an edge of mortality. For the end of the movie I showed the gardener clipping the top of his camel, clipping in a heavenly light, and then walking away in the rain. You know that this garden is not going to last much longer than the gardener's lifetime." Morris dedicated the movie to his mother and stepfather, who had recently died.

Another theme is communication: Morris quotes Mendez as saying that "he's seeking some kind of connection with `the other,' which he defines as that which exists completely independent of ourselves. And then he talks about looking into the eye of a naked mole rat and thinking, I know you are, you know I am. It occurred to me that all of my movies are about language. About how language reveals secrets about people. It's a way into their heads."[9]

Reception

[edit]The film received positive reviews from critics including Roger Ebert[10] and A. O. Scott.[11] On Rotten Tomatoes, it holds a rating of 91% based on 33 reviews.[12] Several critics called it one of the best films of 1997.[13] Ebert wrote that "Errol Morris has long since moved out of the field of traditional documentary. Like his subjects, he is arranging the materials of life according to his own notions. They control shrubs, lions, robots and rats, and he controls them. Fast, Cheap & Out of Control doesn't fade from the mind the way so many assembly line thrillers do. Its images lodge in the memory. To paraphrase the old British beer ad, Errol Morris refreshes the parts the others do not reach."[14]

Soundtrack

[edit]The film's musical score was composed Caleb Sampson and performed by the Alloy Orchestra. It is characterized as circus-like, sometimes frenzied or haunting, and features percussion (particularly mallets and xylophones) to give it a metallic, technological or futuristic flavor. A theme from the score appeared on Leonard Maltin's Critic's Choice Best Movie Themes of the 90s compilation soundtrack.[15]

The film is available on VHS and DVD,[16] while the soundtrack is available on CD.[17]

References

[edit]- ^ Roger Ebert

- ^ Silverman, Jason. "Fast, Cheap & Out of Control Interview With Filmmaker Errol Morris". The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ Resha, David (2015). The Cinema of Errol Morris. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-8195-7534-0.

- ^ Errol Morris: Film

- ^ Emerson, Jim (February 9, 2010). "Death and life of an editor: Karen Schmeer, 1970-2010".

- ^ The New Cult Canon: Fast, Cheap and Out of Control|AV Club

- ^ Resha, David (2015). The Cinema of Errol Morris. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. pp. 131–153. ISBN 978-0-8195-7534-0.

- ^ "Fast, Cheap and Out of Control: A Robot Invasion of the Solar System"

- ^ Ebert, Roger (November 9, 1997). "Way out and in control". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ^ Roger Ebert

- ^ 'Fast, Cheap and Out of Control' | Critics' Picks | The New York Times via official YouTube channel

- ^ Rotten Tomatoes

- ^ Morehead, M. V. (November 13, 1997). "Of Mole Rats and Men". Phoenix New Times.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (November 14, 1997). "Four characters in search of meaning".

- ^ Critic's Choice - Leonard Maltin's Best Movie Themes of the 90s Soundtrack (1993-1999) - soundtrack.net

- ^ Amazon.com

- ^ jazz cds, Accurate Records Caleb Sampson

External links

[edit]- 1997 films

- American documentary films

- Films directed by Errol Morris

- Films produced by Errol Morris

- Collage film

- Films about animals

- Circus films

- American robot films

- Films about insects

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s American films

- American Playhouse

- Sony Pictures Classics films

- English-language documentary films