Armenians in India

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Armenian Christmas at Armenian Church of Holy Nazareth, Kolkata | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Kolkata, Mumbai, Hyderabad, Bangalore, New Delhi, Surat, Chennai, Kochi | |

| Languages | |

| Currently spoken: Various Indian languages and English Traditional: Armenian | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (Armenian Apostolic Church) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Armenian diaspora |

| Part of a series on |

| Armenians |

|---|

|

| Armenian culture |

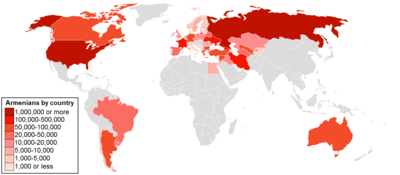

| By country or region |

Armenian diaspora |

| Subgroups |

| Religion |

| Languages and dialects |

|

Armenian: Eastern (Zok) • Western (Homshetsi) Sign languages: Armenian Sign • Caucasian Sign Persian: Armeno-Tat Cuman: Armeno-Kipchak Armenian–Lom: Lomavren |

| Persecution |

The association of Armenians with India and the presence of Armenians in India are very old, and there has been a mutual economic and cultural association of Armenians with India.[1][2] Today there are about a hundred, most of whom currently live in or around Kolkata.

History

[edit]

The earliest documented references to the mutual relationship of Armenians and Indians are found in Cyropaedia (Persian Expedition), an ancient Greek work by Xenophon (430 BC – 355 BC). These references indicate that several Armenians traveled to India.[1][3]

An archive directory (published 1956) in Delhi, India states that an Armenian merchant-cum-diplomat, named Thomas Cana, had reached the Malabar Coast in 780 using the overland route.[2]

The Ottoman and the Safavid conquests of the Armenian highlands in the 15th century CE meant that many Armenians dispersed across the Ottoman and Safavid empires, with some eventually reaching Mughal India (Northern India). [citation needed] During the reign of the Mughal emperor Akbar, Armenians—such as Akbar's wife Mariam Begum Saheba and a Chief Justice Abdul Hai—gained prestige in the empire. While Armenians gained prestige serving as governors and generals elsewhere in the empire such as Delhi, Lahore and the Bengal, living in enclosed colonies and establishing churches.[4] Armenians worked as merchants, gunsmiths, gunners, priests and mercenaries for some of the Islamic rulers in India, with many noted to have served in the armies of various nawabs in Bengal and Punjab, such as Khojah Petrus Nicholas and Khojah Gurgin Khan.[4]

Thomas Cana was an affluent merchant dealing chiefly in spices and muslins. He was also instrumental in obtaining a decree, inscribed on a copperplate, from the rulers of Malabar (present-day Kerala and the Deep-South), which conferred several commercial, social and religious privileges for the Christians of that region. In current local references, Thomas Cana is known as "Knayi Thomman" or "Kanaj Tomma", meaning Thomas the merchant.[citation needed]

Centuries later, an additional incentive for Armenian settlements in India was an Armenian agreement with the British East India Company. The agreement was signed in London on 22 June 1688, and a Julfan merchant, resident in London at the time, signed the treaty on behalf of the “Armenian Nation.” Competing with the Portuguese and the French, the British wanted to boost the Armenian presence in India, and the agreement accorded special trading privileges to the Armenians, as well as equal rights with British subjects regarding the freedom of residence, travel, religion, and unrestricted access to civil offices.[citation needed]

Due to Armenians not having a country of their own, the colonial powers of Europe massively favored trading with Armenians compared to their European counterparts during the age of mercantilism. Most notably, they became an intermediary between the Spaniards and the English. Armenians were known for their honesty.[5] Hence, it made them a great candidate to become international traders. Armenians grew to be very wealthy in India; due to their wealth, they established their own settlements in various Indian cities where they constructed their churches, newspaper publications, and even the first-ever Armenian constitution was written in Madras, India, 1773, by Shahamir Shahamirian, 14 years before the American constitution was written. Armenian trade network stretched from Manila all the way to Amsterdam. However, undoubtedly, Armenian traders were most successful in India.[6]

Former settlements

[edit]

Several centuries of presence of Armenians resulted in the emergence of a number of several large and small Armenian settlements in several places in India, including Agra, Surat, Mumbai, Kanpur, Chinsurah, Chandernagore, Calcutta, Saidabad, a suburb of Murshidabad, Chennai, Gwalior, Lucknow, and several other locations currently in the Republic of India. Lahore and Dhaka – currently respectively in Pakistan and Bangladesh, – but, earlier part of Undivided India, and Kabul, capital of Afghanistan, also had an Armenian population. There were also many Armenians in Burma and Southeast Asia.[citation needed]

- Agra

Akbar (1556–1605), the Mughal emperor, invited Armenians to settle in Agra in the 16th century,[7] and by the middle of the 19th century, Agra had a sizeable Armenian population. By an imperial decree, Armenian merchants were exempted from paying taxes on the merchandise imported and exported by them, and they were also allowed to move around in the areas of the Mughal Empire where entry of foreigners was otherwise prohibited. However, for the Armenians, who were recognized by the emperors for their innovative skills, earned their exceptional status in India. In 1562, an Armenian Church was constructed in Agra.[citation needed]

- Murshidabad

Aurangzeb (1658–1707), a Mughal Emperor, issued a decree which allowed Armenians to form a settlement in Saidabad, a suburb of Murshidabad, then the capital of Mughal subah (province) of Bengal. The imperial decree had also reduced the tax from 5% to 3.5% on two major items traded by them, namely piece goods and raw silk. The decree further stipulated that the estate of deceased Armenians would pass on to the Armenian community. By the middle of the 18th century, Armenians had become a very active, vibrant merchant community of Bengal. In 1758, Armenians had built a Church of the virgin Mary in Saidabad's Khan market.[citation needed]

- Surat

Armenian gravestones from the 16th and 17th centuries in Surat, India, reflect the historical presence of the Armenian community in the region. These gravestones, featuring intricate designs and inscriptions, are part of the Armenian cemetery in Surat, alongside the cemeteries of early British and Dutch settlers. Historians suggest Armenians began settling in Surat as early as the 14th century, with a notable increase in the 16th century.[8]

The Armenians in Surat were primarily traders, dealing in jewelry, precious stones, cotton, silk, and other commodities. They engaged in trade with Armenian-owned merchant vessels, exporting goods to various destinations including Egypt, the Levant, Turkey, Venice, and Leghorn. Unlike other traders from West Asia who often traveled alone, Armenian merchants often brought their families with them.[9]

16th century onwards, the Armenians (mostly from Persia) formed an important trading community in Surat, the most active Indian port of that period, located on the western coast of India. The port city of Surat used to have regular sea borne to and fro traffic of merchant vessels from Basra and Bandar Abbas. Armenians of Surat built two Churches and a cemetery there,[citation needed] and a tombstone (of 1579) in Surat bears Armenian inscriptions. The second Church was built in 1778 and was dedicated to Mary.[citation needed] A manuscript written in Armenian language in 1678 (currently preserved in Saltikov-Shchedrin Library, St. Petersburg) has an account of a permanent colony of Armenians in Surat.[10]

The British valued the business acumen of the Armenian community and sought their cooperation to secure trading privileges in the Mughal court. Today, the Armenian gravestones in Surat stand as a reminder of the community's contributions to the city's history and its commercial and cultural ties with various regions.[11]

- Chennai

Landmarks of contributions made to the city of Chennai still exist. Uscan, an Armenian merchant who had amassed a fortune from trade with the Nawab of Arcot, invested a great amount in buildings. The Marmalong Bridge, with many arches across the river Adyar was constructed by him, and a huge sum of maintenance donated to the local authorities. Besides building rest houses for pilgrims, he built the Chapel of Our Lady of Miracles in Madras. The only reminder of the bygone era is the Holy Virgin Mary church of 1772 at 2/A Armenia Street, Georgetown).The Armenia India legacy in Chennai and Armenian contributions are well documented in the Armenia Virtual Museum [12]

- Kolkata

The Armenians settled in Chinsurah, near Kolkata, West Bengal, and in 1688 built a Church there which is now known as Armenian Church of the Holy Nazareth This is the second oldest Church in Bengal and is still in well preserved on account of the care of the Calcutta Armenian Church Committee.[13][14]

Demography

[edit]

Population

[edit]After Armenia's independence from USSR, many Armenian-Indians chose to return to their ancestral homeland. Now there are hardly 100 Armenians in India, mostly in Kolkata. Kolkata still has about 150 Armenians and they still celebrate Christmas on 6 Jan,[15] and Easter.[16] Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day is also observed in Armenian Church, Kolkata.[17] The Armenian Church of Holy Nazareth, located in Brabourne Road, Kolkata was constructed in 1734 and is the oldest Church in Kolkata.[17] The best known Armenian institution in India is the Armenian College and Philanthropic Academy (est. 1821)[18] better known as the Armenian College, in Kolkata, funded by endowments and donations. The management of the college was handed over to the Armenian Holy See of Echmiadzin of the Armenian Apostolic Church some years ago by a group of alumni led by Heros Avetoom. There are presently around 125 children studying there from Armenia, Iran and Iraq and the local Armenian population. There is also the Armenian Sports Club (est. 1890) which is still active.

Last names of Armenians settled in India

[edit]- Arakiel

- Arrathoon

- Avetoom

- Aviet

- Apcar

- Chater

- Cheriman

- de Murat

- Galstaun

- Gaspar/Gasper

- Gregory

- Jordan

- Minas

- Pogose

- Sarkies

- Satur

- Sookias

- Armen

- Mehr

- Seriman

- Sherimanian

Religion

[edit]

Most Armenians in Armenia are Apostolic Orthodox and adhere to the Armenian Apostolic Church and are under the jurisdiction of the Holy See of Echmiadzin. In February 2007, Karekin II, Catholicos of All Armenians visited India. In Delhi he met with the President of India. He also visited Chennai, Mumbai and Kolkata. There are many Armenian Apostolic Orthodox churches in India:

- Kolkata

- Armenian Church of Holy Nazareth, Kolkata

- Armenian Church of St.John the Baptist, Kolkata

- Armenian College and Philanthropic Academy, Kolkata

- Armenian St. Gregory's Church, Kolkata

- The Holy Trinity Chapel (Church of Tangra), Kolkata

- Other places

- Armenian Church, Chennai

- St. Peter's Armenian Apostolic Church, Mumbai

- St. Mary Armenian Church in Saidabad, Murshidabad

Armenia–India relations

[edit]

President Levon Ter-Petrossian visited India in December 1995 and signed a Treaty of Friendship and Co-operation. Foreign Minister Vartan Oskanian traveled to India in December 2000. India's Minister of State for External Affairs Mr. Digvijay Singh visited Armenia in July 2003. President Robert Kocharian, accompanied by several Ministers and a strong business delegation, visited India in October–November 2003.[19]

The Armenia-India Friendship Society (within the Armenian Society for Friendship and Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries) regularly marks India's Republic and Independence Days.[citation needed]

Prominent people

[edit]- Abdul Hai was the Chief Justice of Mughal Empire during the time of Akbar.

- Khwaja Israel Sarhad was an eminent Judeo-Persian merchant of Armenian origin in Bengal during the late 17th & 18th centuries. He was from New Julfa (Isfahan, Iran), nephew of the renowned Khwaja Fanous Kalantar—in 1688, the latter had affirmed an agreement with the English East India Company in London on behalf of the Armenian nation. He obtained permission from the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb in 1698 that allowed the English to financially acquire from the existing holders the right to rent the three villages of Calcutta, Sutanati, and Govindpore for the grand sum of sixteen thousand rupees.[20]

- Eliza Kewark or Kevork whose father was Armenian was the wife of Theodore Forbes, making her the fourth great-grandmother of Lady Diana.

- Gauhar Jaan (born Angelina Yeoward) was an Indian singer and dancer (or tawaif) of Armenian origin from Calcutta.

- Juliana, believed to be a sister of one of Akbar's Armenian wives, was a doctor in the royal harem of Akbar. Lady Juliana built the first Church in Agra. She was later married to Jean Philippe de Bourbon of Navarre, a royal descendant of France.

- Mariam Zamani Begum, one of the wives of Akbar, was believed to be an Armenian. Marium Zamani Begum's palace still stands in Fatehpur Sikri, Uttar Pradesh, India. But now most historians agree that Mariam Zamani was the First Hindu Wife of Akbar and the princess of Amber.

- Mariam Begum Saheba, also known as Vilayati Begum (literal meaning English Queen) was married to a king of Oudh, when the British conferred on him the title of King in 1814.

- Mirza Zul Quarnain, adopted son of Akbar and his Armenian wife, was an Armenian. He was well versed in several languages, particularly Portuguese. Upon the death of his father in 1613, he succeeded as a collector of tax levied on salt produced in Sambhar (Rajputana). His rise was fast and he held positions in turn as the Governor of Sambhar, Mogor, Babraich (Oudh), Lahore and Bengal. Emperor Jahangir conferred on him the title of Amir. He also maintained very cordial relations with Jesuits in India of his time. Mirza was also a poet, singer and playwright, and he composed verses in Urdu and Persian.

- Sarmad Kashani (a Persian word for "eternal"), an Armenian of Aurangjeb's (1658–1707) time was a scholar and a mystic saint and his grave is near the Jama Masjid. His poetic talents are often compared with gifted poets like Firdausi, Sayadi, Hafez and Khayam. He was allegedly executed by Aurangzeb in 1671.

Medical professionals

[edit]- Arthur Zorab, an eye specialist, perfected an operating style for glaucoma, which was named after him as the "Zorab operation".

- Frederick Joseph Satur (Indian), Army Medical Corps M.B., B.S, DV. Graduated From Madras Medical College 1938. Saw active service in North Africa WW2 Indo-China war of 1962 UN Peace Keeping force Hospital Congo 1960. Retired fro service in 1969.

- Joseph Marcus Joseph, M.D., an Armenian joined the Indian Medical Service in 1852 and rose to the level of Deputy Surgeon General by 1880. The Indian Army, under the British, had several Armenians Lieutenant Colonels, Surgeon Captains, and Surgeon Majors.

- Marie Catchatoor, an Armenian lady, was the first woman of India to be appointed as Presidency Surgeon of West Bengal. She retired in the early 1980s as the superintendent of Lady Dufferin Hospital, Calcutta.[17]

- Sargis Avetoom of the Indian Army, participated in British Army's actions in Afghanistan, Egypt and Burma, and was honored by the British Government, Medal and Clasp and Khedives star with Clasp from Egypt, and Medal and Clasp from Burma. He discovered a medicine for dysentery, and was fluent in many languages like Armenian, Russian, English, German, Hindi, Belugi and Pashto.

- Stephan Manouk, son of a prominent business man, Hovsep Manouk, obtained a Diploma Of Doctor Surgeon from the Royal Medical University, London, in 1862. His services during a cholera epidemic of that time earned him a Certificate of Honors by the British Government.

- Stepen Owen Moses pioneered St. John's Ambulance Courses in Calcutta,[17] and initiated the first Red Cross ambulance in Calcutta during the World War I.

Legal profession

[edit]- Gregory Paul, who had graduated from the Cambridge University, held different posts in the High Court in India.[17]

- M. P. Gasper, a leading barrister of the Calcutta High Court, was the first Armenian who passed the Indian Civil Service Examination in 1869.

Other professions

[edit]

- Coja Petrus Uscan led the Armenian community in Madras. He constructed the Marmalong Bridge across the River Adyar and the steps to the chapel on top of St Thomas Mount.

- Gregory Charles Paul (1831–1900) an Armenian born in Calcutta, educated at Cambridge University, was the Advocate General of Bengal during British rule. He served as Advocate General for more than 30 years, he was knighted. He is buried in the Greek Cemetery, Narkeldanga. The Armenian Church committee at this death refused to allow him to be buried in the Armenian Church precincts. He and other eminent Armenians Barristers of the day brought the Calcutta Armenian Trusts under the Administration of the Calcutta High Court in 1888. (John Gregory Apcar and ors versus 1. Thomas Malcolm and 2. Sir Gregory Charles Paul, Advocate General of Bengal, Calcutta High Court 1888. Two Trusts were formulated by them one for the Management of the Armenian Charity Trusts managed by the officers of the Armenian Church and another Trust for the Management of the Armenian College and Philanthropic Academy. (Advocate General vs Arabella Vardon, Calcutta High Court). Formation of these Trusts have allowed the sustainment of the small Armenian Community in India.

- Harutyun Shmavonyan (Armenian: Հարություն Շմավոնյան) published Azdarar, the first Armenian Language newspaper ever published in Madras on 14 October 1794.

- Joseph David Beglar (1845–1907) an archeologist in the Public Works Department of British India, was associated with significant archeological excavations, which included excavations of Mahabodhi Temple complex in Bodh Gaya, India.

- Thomas Malcolm (1837–1918) / Warden of the Armenian church for 50 years / born 1837 Bushire, Persia / died 6 Mar 1918 Calcutta India. The grave marker is at the Armenian Church Cemetery Lower Circular Road.[21]

- Catchick Paul Chater (8 September 1846 – 27 May 1926) was a Hong Kong based business man, who was born and raised in Kolkata

Sports

[edit]- Mac Joachim (1925–2013), boxer from Calcutta who competed in the 1948 Summer Olympics.

See also

[edit]- Armenia–India relations

- Armenians in Bangladesh

- Armenians in Pakistan

- Armenians in Afghanistan

- Armenians in Iran

- Armenians in Tunisia

- Armenians in Lebanon

- Armenians in Palestine

- Armenians in Jordan

- Armenians in Libya

- Armenians in Egypt

- Armenians in Oman

- Armenians in Myanmar

- Andin. Armenian Journey Chronicles

- Buddhism in Armenia

References

[edit]- ^ a b India and Armenia Partners - Embassy of India in Armenia [ENG] Archived 20 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Anusha Parthasarathy (30 July 2013). "Merchants on a mission". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- ^ Maclagan, E. D. (July 1938). "Armenians in India from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. By Mesrovb Jacob Seth. 8½ × 5, pp. xv + 629. Calcutta: Published by the Author, 1937. Rs. 10 or 15s". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 70 (3): 446–447. doi:10.1017/s0035869x00077947. ISSN 1356-1863.

- ^ a b Seth, Mesrovb Jacob (1895). Armenians in India, from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. ISBN 1593330499.

- ^ Aslanian, Sebouh (2011). From the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean. doi:10.1525/9780520947573. ISBN 9780520947573.

- ^ Seth, Mesrovb Jacob (1983). Armenians in India, from the Earliest Times to the Present Day: A Work of Original Research. ISBN 9788120608122.

- ^ "JULFA v. ARMENIANS IN INDIA – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ Ani, Margaryan. "THE 16TH-17TH CENTURIES' ARMENIAN GRAVESTONES – A TESTAMENT TO THE ARMENIAN PRESENCE IN SURAT, INDIA". Chinarmart.

- ^ Ani, Margaryan. "THE 16TH-17TH CENTURIES' ARMENIAN GRAVESTONES – A TESTAMENT TO THE ARMENIAN PRESENCE IN SURAT, INDIA". Chinarmart.

- ^ Maclagan, E. D. (July 1938). "Armenians in India from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. By Mesrovb Jacob Seth. 8½ × 5, pp. xv + 629. Calcutta: Published by the Author, 1937. Rs. 10 or 15s". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 70 (3): 446–447. doi:10.1017/s0035869x00077947. ISSN 1356-1863.

- ^ Ani, Margaryan. "THE 16TH-17TH CENTURIES' ARMENIAN GRAVESTONES – A TESTAMENT TO THE ARMENIAN PRESENCE IN SURAT, INDIA". Chinarmart.

- ^ "Armenia Virtual Museum - Armenia in India A Cultural Legacy - Armenian Cultural Centre Chennai". CogniShift.Org. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ^ "History - The Armenian Holy Nazareth Church Calcutta". freepages.rootsweb.com. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Armenian Church of the Holy Nazareth". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Kolkata, Armenian celebrates Christmas". Business Line. 6 January 2004. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ Datta, Rangan (21 April 2013). "Easter with Armenians". The Telegraph, Kolkata. Calcutta, India. Archived from the original on 4 February 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Banerjee, Poulami (23 May 2010). "Church Children". The Telegraph. Calcutta. Calcutta, India. Archived from the original on 4 February 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ Armenian College and Philanthropic Academy official website Archived 26 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Armenia - Armenia India Bliateral Relations". Archived from the original on 26 December 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- ^ Husain, Ruquiya K. (2004). "Khwaja Israel Sarhad: Armenian Merchant and Diplomat". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 65: 258–266. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44144740.

- ^ in India by M J Seth page 444 (in reprint 2005 edit.).

Further reading

[edit]- Jacob Seth Mesrovb, Armenians in India - From the Earliest Times to the Present, Calcutta, 1937

- THE ARMENIANS OF INDIA: An Historical Legacy by David Zenian. AGBU

- The saga of an Armenian family of Old Dhaka

- Recovering the stories of the Armenians of Asia